From the beginning, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera’s relationship was an exceptional blend of passion and turbulence. Only a few days after meeting, the famous Mexican muralist began an affair with the 18-year-old art student 20 years his junior. Their three-decade love story would go on to become one of the greatest romances in the history of art.

“I did not know it then, but Frida had already become the most important fact in my life. And she would continue to be, up to the moment she died, twenty-seven years later,” Rivera wrote after knowing the adult Frida for only a few days. (Rivera soon recognized Frida as the same young girl who had watched him intently as he painted a mural several years earlier.)

But while they were each others’ greatest loves, they encountered more than a few road bumps throughout their lives together. Rivera was a notorious and unapologetic womanizer; Kahlo responded in kind, conducting illicit liaisons of her own that allegedly included trysts with communist revolutionary Leon Trotsky and famed dancer Isadora Duncan.

The emotional turmoil of her marriage and her all-consuming love for Rivera inspired much of Kahlo’s work, including The Wounded Table, one of the artist’s biggest and most intricate pieces that hasn’t been seen since it disappeared in the mid 1950s.

The first decade of the Rivera-Kahlo marriage had many ups and downs. The couple traveled the world as Rivera was feted for his increasingly renowned work and Kahlo’s paintings started to gain attention.

Kahlo struggled with the loss of two pregnancies and the realization that she wasn’t going to be able to have a child due to severe injuries she suffered when she was young, injuries that would ultimately leave her crippled and in need of countless surgeries over the course of her life. And, of course, despite their undying fervor for each other, they each had dalliances on the side.

But Rivera took his infidelities one step too far. Kahlo discovered that her beloved husband had conducted an affair with her younger sister Cristina. At the end of 1939, the two decided to divorce.

Ultimately, Rivera and Kahlo wouldn’t be able to stay apart—the divorce only lasted a year. But the split shook Kahlo’s life to its core and resulted in her emotional painting, The Wounded Table, created for the International Exhibition of Surrealism in Mexico City in 1940.

“Diego was the motor of her life. It’s not a feminist thing to say, and the feminists made her a heroine. But in fact she adored him, she was lost without him,” said art historian Frances Borzello in a video for Lost Art, a project of the Tate in London.

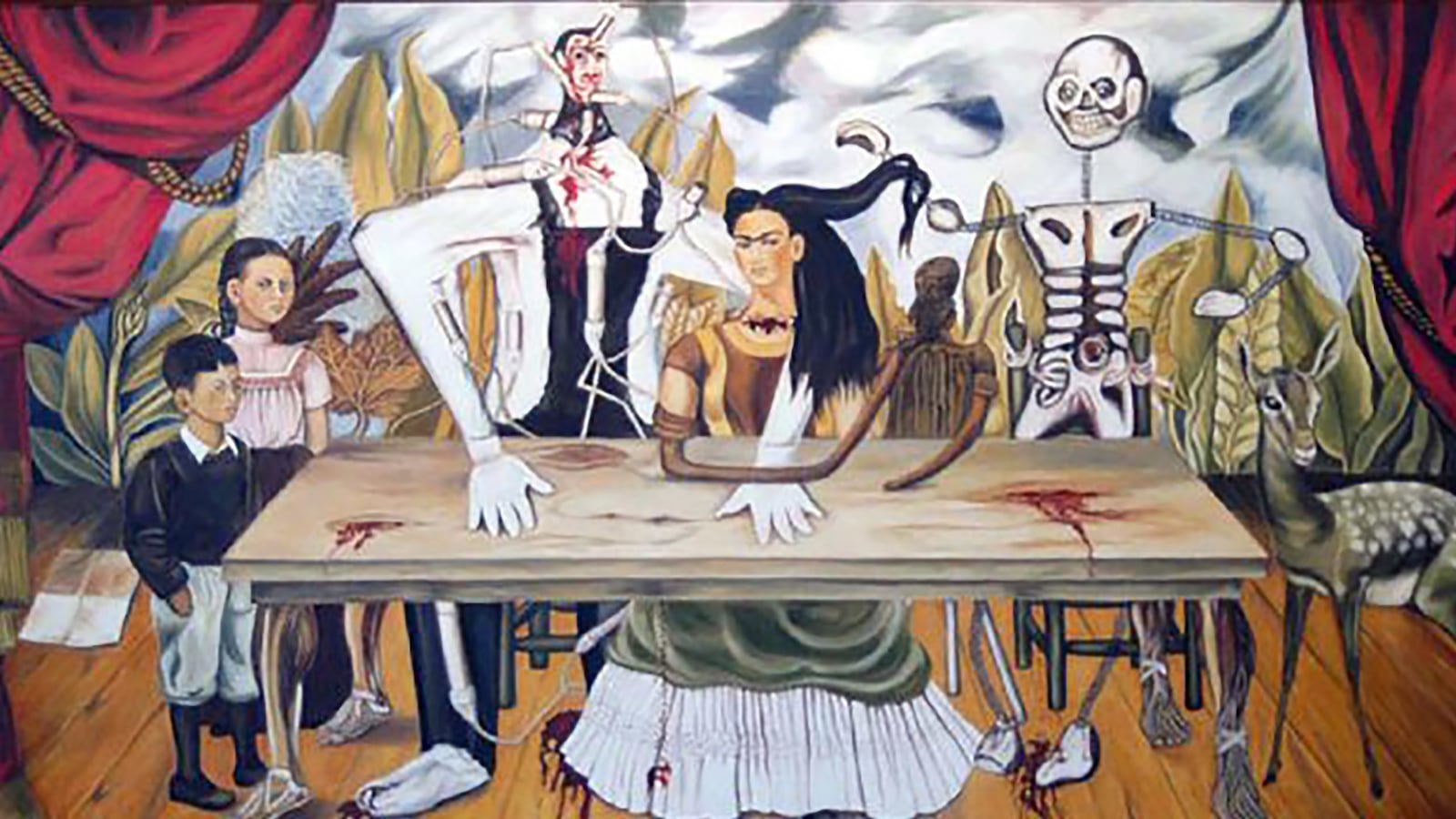

The Wounded Table is a nod to Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, with the figures in the painting staring out at the viewer from behind a wooden table that is supported by what appear to be human legs with exposed tendons and bone. Kahlo painted herself in the center of the table in the position of the martyr.

She’s dressed in traditional folk attire with her characteristic long black hair and prominent unibrow. Blood seeps out of cuts in the table, pools on the ground next to her full white skirt, and drips down the face of the hulking figure to her right.

That man, meant to signify Judas, is dressed in overalls that identify him as Rivera. To Kahlo’s left are an Aztec sculpture and a skeleton. All four figures are intertwined, with the painter’s hair wrapped around the skeleton’s hand, the sculpture’s right arm reaching across her front to fuse with her own right arm, and the giant arm of Rivera draped over her shoulder possessively.

The only figures who stand apart from this tableau are those of her beloved niece and nephew who appear young and unscathed on the right side of the table, and a similarly innocent fawn that stares out at the viewer from the left.

The image is a theatrical one, with giant red curtains tied back on either side as if the scene is taking place on stage against a backdrop of stormy skies and indigenous plants, a common motif in Kahlo’s work.

“The Wounded Table is first and foremost a painting of betrayal,” Borzello said. “She never wanted to be pitied. She’s defiant after the divorce. She’s saying I can do these giant things, I can do anything. You can see she’s achieved really a maturity.”

Kahlo worked frantically to finish the painting in time for the Mexico City exhibition, but, once there, she wasn’t entirely pleased with its reception. “Unfortunately, I don’t believe my work has interested anyone. There’s no reason why they should be interested and much less that I should believe that they are,” Kahlo wrote in a letter to Rivera.

Less than a year after their divorce, Kahlo and Rivera rekindled their romance and were married again in late 1940 in San Francisco. A trove of personal letters discovered in 2004 revealed that Kahlo’s doctor helped convince the artist to return to the love of her life—and also that Rivera wasn’t going to change his womanizing ways.

“Diego loves you very much, and you love him. It is also the case, and you know it better than I, that besides you, he has two great loves: 1) painting 2) women in general. He has never been, nor ever will be, monogamous,” Dr. Leo Eloesser wrote to Kahlo. The two would remain married until Kahlo’s death in 1954 at the age of 47.

But while their love was saved, the fate of The Wounded Table was not quite so lucky. In 1946, Kahlo handed the painting over to the Russian Ambassador to Mexico; it was last seen at an exhibition in Warsaw in 1955. From there, no one knows what happened to the piece and it has since been classified as lost.

After Kahlo’s death, her work dramatically increased in popularity and she attained something of a cult following. In 2016, Kahlo’s painting Dos Desnudos en el Bosque (La Tierra Misma) sold for $8 million, making her one of the top 10 most expensive women artists of 2016 according to artnet News.

So, any Kahlo paintings that turn up are sure to be met with eager interest, and as with all lost art, there’s hope that one day it will be found. Maybe it will be discovered in the corner of a museum basement or a home attic where it was stashed away and forgotten all these years, maybe in a shipping crate that was thought empty and overlooked since that Polish exhibition decades ago.

But, if it does turn up, that doesn’t mean it will be all smooth sailing for The Wounded Table. One major question remains: Who actually owns the painting?

Little is known about the deal Kahlo made with the Russian ambassador. What was surely just an administrative detail to the artist at the time has become a larger question as the specifics of that agreement have been lost with her death. Did the artist entrust the painting to the ambassador merely as a loan for a few years? Or was it a gift from Kahlo, an avowed communist supporter, to the motherland? Without knowing the answers to these questions, there’s sure to be a major fight for the painting if it ever does resurface.

Until then, we are left with only a few images of the painting that were taken before it vanished and the trove of love letters and paintings by Kahlo and Rivera that have kept their love alive long past their deaths.

As Frida once wrote to Diego, “I sing, sang, I’ll sing from now on our magic—love.”