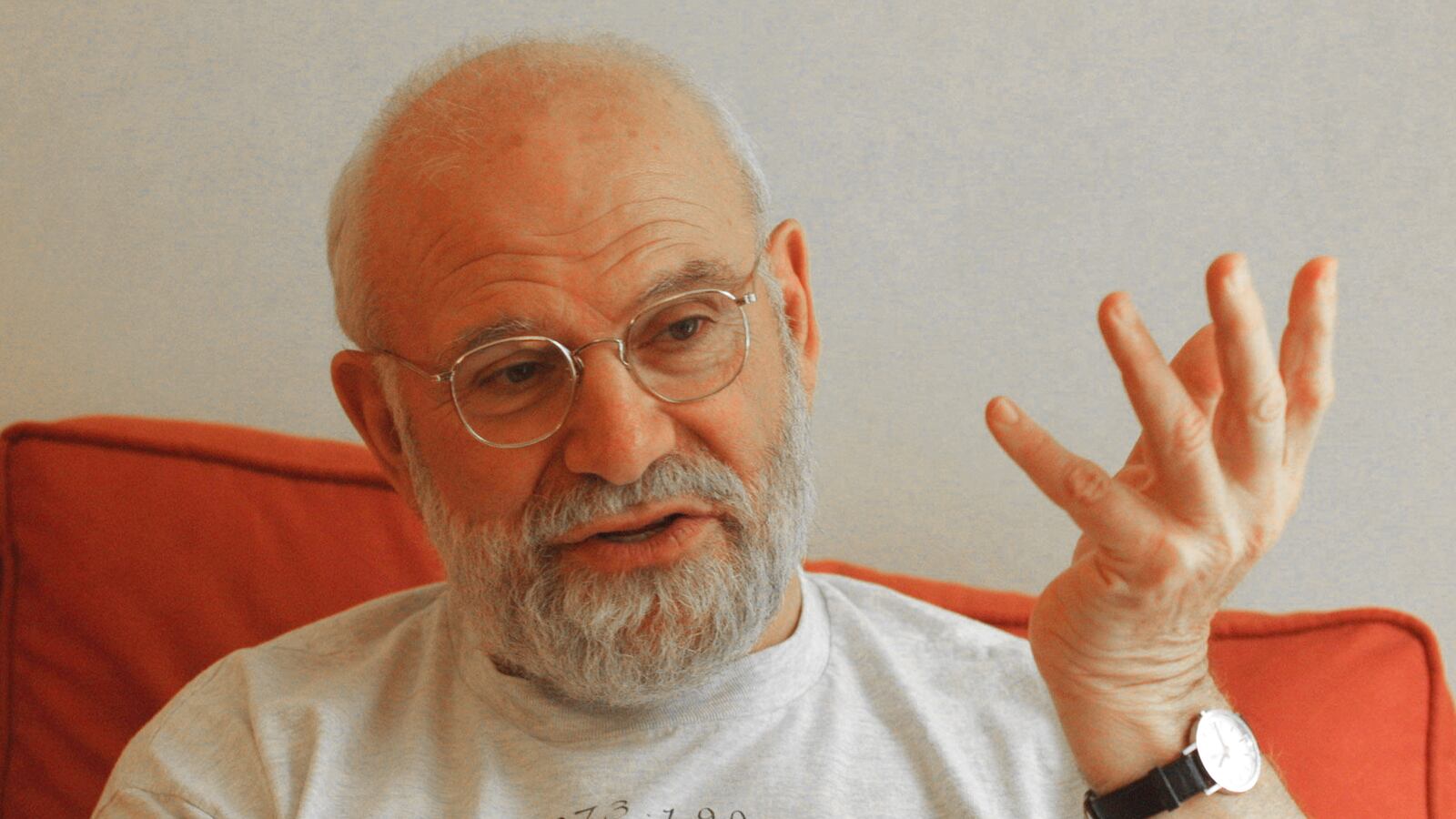

Editor's Note: On Sunday, August 30, 2015, Oliver Sacks died in his home in New York City after a battle with cancer at the age of 82.

Please recommend a book that makes science accessible to trade readers, and that has influenced your own work.

One book that was very influential for me was published in English in 1968, and it’s called The Mind of a Mnemonist, by A. R. Luria. When I started to read the book, I thought it was a novel. Then after a few pages I realized it was a case history, the most detailed I ever read, but so beautifully written, and so full of feeling and pathos and characterization and richness … For me, that combined science and art ideally. That’s my model.

For readers coming to your books for the first time, which would you recommend as a starting point, and why?

I think maybe The Island of the Colorblind. I have a sort of soft spot for it, because it combines different sorts of writing. It has medical writing, but it also has travel writing: going to Micronesia to see this island of colorblind people. I think it’s broader and more colorful than my purely medical books.

You have researched a wide variety of neurological phenomena, including Tourette’s syndrome and migraines. What about when a condition or phenomena speaks to you, and prompts your desire to study it in detail?

Tourette’s syndrome is a good example. There, people who have it severely may not only make sudden tics and movements and barks, occasionally curses, but their perceptions are accelerated, their imagination is heightened, and sometimes there’s an almost convulsive reflection of all they perceive in the form of imitation. It is so complex and so extraordinary that, even though I first saw a patient with it more than 40 years ago, and I wrote about him in The Man Who Mistook his Wife for a Hat, I am still amazed and enchanted, both by what I see and what it shows that the brain is capable of. In particular, it shows what it’s like to move and think much faster than normal—the advantages, but also the disadvantages, of this.

While going over your new book, it occurred to me that reading about a multi-sensory phenomenon like hallucinations might not be as effective in understanding them as a multi-sensory experience would be. A film or a ride, for instance, which could include visual and audible sensations.

Well, firstly [there is] the difficulty of writing about any experience, because experience is always richer than language [although language can focus on different aspects of it]. In Hallucinations, I’m writing about other people’s experience … no, wait, that’s not quite true, there’s also a scandalous chapter on my own experiences … Well, I think a page of print is not adequate to convey what a multi-sensory experience is like, you’re right. A multi-sensory experience is, well, opera, which I love. There’s music, there’s theater. The words and the music and the actions all have to blend together. Though lots of hallucinations are not multi-sensory, just one sense at a time. Perhaps opera would be a more vivid way to present it, but I had to write a book, you see.

Describe your morning routine.

I usually get up fairly early, I got up at 4:30 this morning, but I usually get up between 6 and 6:30. I always have a pad on my bedside, in case I want to write straight away. I also have a habit at night of leaving a sentence unfinished, so I can pick up on it the next morning. I’m also a bit afraid of going to sleep. If writing is flowing, I’m afraid it might disappear. I’m also slightly afraid of mealtimes. If the mood is upon me, I tend to write nonstop. But I’m not very systematic. There are mornings when I don’t write, and others when I can’t be stopped.

I get up, a pad by my bedside. I have my usual breakfast of oatmeal, again with a pad in the kitchen, because you never know what’s going to go through your mind when you’re eating your oatmeal. I then usually go for a walk. I like to walk before 7, when there are not too many people around, and there’s something about exercise that gets my mind going.

Describe your writing routine, including any unusual rituals associated with the writing process, if you have them.

I’m not all that systematic. There’s an important preliminary. I have to have pen and paper always available, not only in the office and in my apartment, but if I go for a walk, then ready in my pocket. It infuriates me not to be able to write something that has popped into my mind.

I get to the office around 8. I always find that paperwork has accumulated. I get, I don’t know, well over 1,000 letters from readers per year. When I answer an email I use my fountain pen, which means that the correspondents need to give me a postal address. I find the physical act of using a pen gets me going. But also the act of communicating by writing letters also gets me going. Letter writing tends to lead on to book writing.

On Friday morning, I went to see patients at a place I’ve gone for many years. There, seeing people, although I’ve seen all sorts of conditions for 40 years or more, they still amaze me. I keep copious notes. Sometimes those copious notes turn into articles or books, though usually years later. Monday morning was an unusual one. I had to be at another hospital because I watched a brain operation. The morning tends to be my high-energy time, and I usually write in the morning.

What is something you always carry with you?

I have a special pad, waterproof paper, and a waterproof pen that I take with me when I go on botanical excursions, but also I sometimes keep it by the side of the swimming pool, because I swim every day, and sometimes ideas occur to me in the water.

What is guaranteed to make you laugh?

Ooh, good question. The Marx Brothers, I suppose.

What is guaranteed to make you cry?

Yes, I cry fairly easily. I’m a sentimental slob for various operas. When Mimi dies in La Boheme, I can’t help shedding a tear.

Do you have any superstitions?

Some superstitions I object to—for instance, my building doesn’t have a 13th floor. I’m sure I have lots of them, because I’m a bit on the obsessive side. Ah, yes. In general, I feel that, unless I put things in certain places, they will surely be lost.

What is your favorite snack?

I’m afraid I do often tend to snack while writing. I try to get away from candies, and things I like are peas. So I often have a bowl of shelled peas.

What phrase do you overuse?

Yes, I’m usually not conscious of the ones in speech, but then I’m appalled when I listen to myself. I think phrases like “sort of” get into my speech and I’m not aware of them. In writing I tend to use “as it were” and “so to speak” too often.

Tell us a funny story related to a book tour or book event.

When The Man Who Mistook His Wife For a Hat came out in 1986, I had an interview on the radio in San Francisco with call-in listeners. One of the people who called in said, “I can’t recognize my wife either, though I don’t mistake her for a hat.” He went on to say that he doesn’t recognize anyone or anything. He said he had a rare brain tumor. I said, “How very interesting and extraordinary. Why don’t I meet you at the radio station after the show?” In fact he came along, and I saw him as a patient, in a way … I didn’t charge or anything, but I visited him several times, and encouraged him to form a support group for people with recognition problems like his own.

Tell us something about yourself that is largely unknown and perhaps surprising.

Well, I blurted out some of my dark history in Hallucinations, so much of it is known now. People who see me now, as an old man, may have difficulty believing that I used to love motorcycles, and even race them. Yes. As a young man, of course. And even now, the sound of a good, highly-tuned engine sets my pulses pounding!

What would you like carved onto your tombstone?

“He tried.”