The infiltration in the winter of 2013 was insidious in the small rural towns circling Aleppo—Tel Rifat, al-Bab, and Marea. The men stood out when you bumped into them on the streets of the towns recently liberated from the forces of President Bashar al-Assad. They were more disciplined than local rebels; they dressed more neatly, their beards were trimmed. But they held themselves apart from the other rebels, and questions from Western reporters about who they were and what they were doing went unanswered.

In hindsight, this was the beginning in northern Syria of ISIS, and the men who were all too often taken by the locals to be members of al Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra were in fact preparing the ground to replace their fellow jihadists and to lay the foundations for a caliphate.

New documents unearthed by Der Spiegel journalist Christoph Reuter shed light on the furtive early plotting in Syria that laid the groundwork for ISIS’s caliphate. The files Reuter discovered add to an understanding of ISIS that has evolved, often without a full picture coming into focus.

In the immediate wake of the departure of government forces from the small northern Syrian towns and villages in the winter of 2013, there was considerable chaos. Each town struggled to establish some governance structure. There was scant command and control of the motley rebel militias who were now focused on securing districts that insurgents captured in Aleppo, and there was a lot of corruption and lawlessness, with aid and arms supplies pilfered. Disputes rose over the sharing of weapons and equipment seized from government barracks and bases.

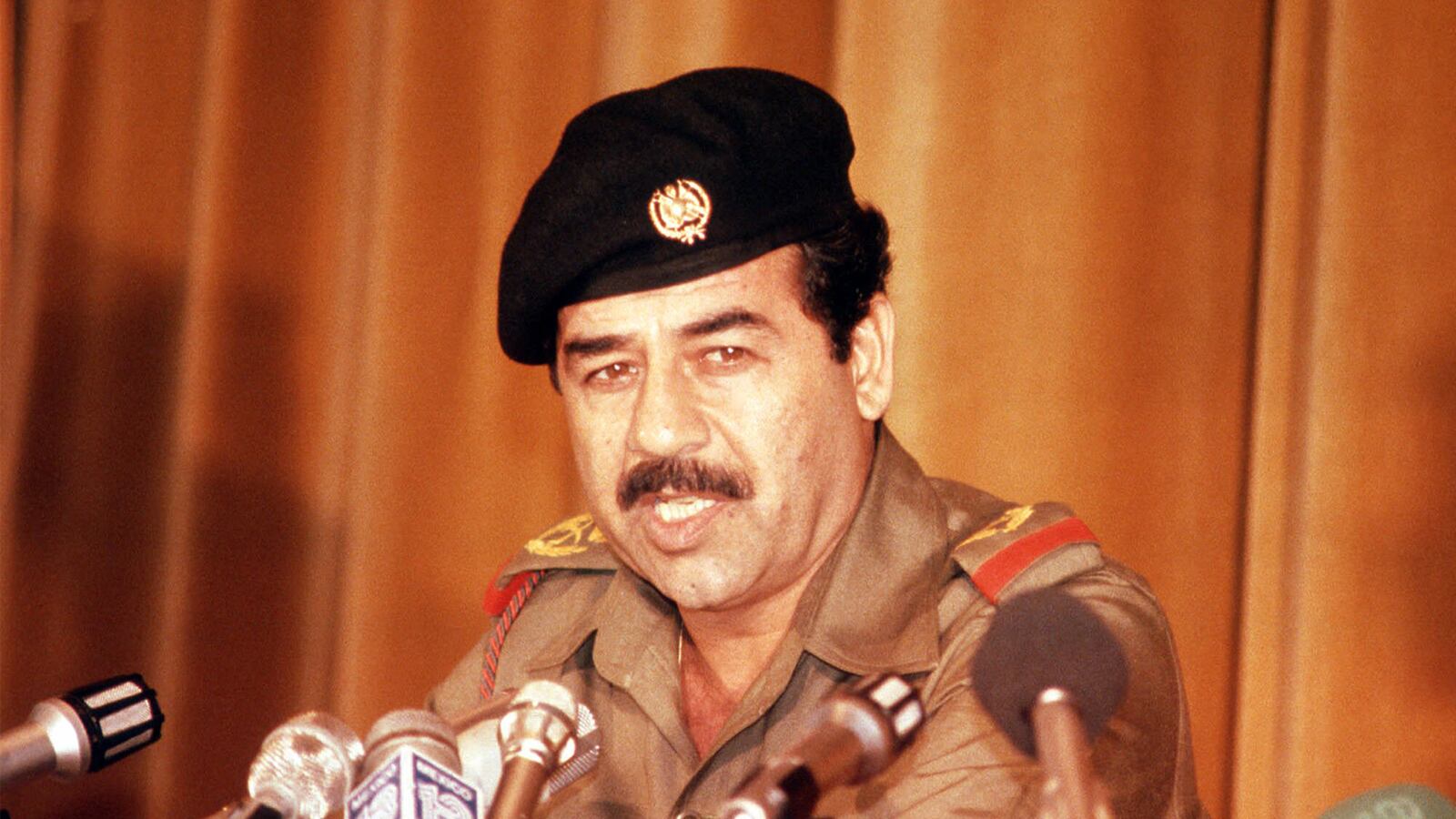

The groundwork for the rise of ISIS was built in the confusion, with careful and meticulous intelligence and surveillance work—as now highlighted in the trove of documents, some handwritten, by one of Saddam Hussein’s former intelligence officers and accessed by Der Spiegel. The 31 pages of lists and schedules and charts drawn up by Samir Abd Muhammad al-Khlifawi, a former colonel in the intelligence service of Saddam’s air defense forces who went by the pseudonym Haji Bakr, reveal, says the magazine, the espionage effort behind the establishment of ISIS. The documents also demonstrate the crucial role played in its emergence by former members of Saddam’s military and spy agencies.

The papers, which were found in a house Bakr occupied in Tel Rifat before being killed in a firefight with rebels in January 2014, amount to an organizational blueprint. They detail plans for the establishment of the policing of the caliphate, the chains of command for internal security, and the surveillance priorities for laying the groundwork necessary for infiltration to be transformed into takeover. Bakr wanted his men as they fanned out across Syria to study the tribal power structures of each town and uncover the local leaders’ vices and weaknesses in case the information could be used to blackmail them or force them into subjugation.

And the plotting and scheming paid off. Much that Bakr outlined—especially in terms of the chains of command and organizational structure for internal security and enforcement—has been put into ferocious practice.

That includes shaping parallel intelligence structures, so the spooks and enforcers in the totalitarian caliphate spy on each other to ensure loyalty. Across northern and eastern Syria and western Iraq, the militants of ISIS are able to govern thanks partly to Bakr’s groundwork and his drawing on expertise honed in Saddam’s Republic of Fear. Now the militants, with an iron fist and a sharp eye, purge opponents and brook no opposition, intolerant of any expressions of dissent or behavior diverging from their diktats, no matter how trivial or innocuous.

Outside of ISIS’s reliance on spies and assistance in administering cities under its control, there are other signs of Baathist influence in the group. The blitzkrieg assaults that captured key Iraqi cities last summer showed signs of experienced military planning hard to come by for terrorist and insurgent organizations more versed in ambushes and hit-and-run tactics.

The Der Spiegel article, though based on original documents, builds on a growing body of work. Numerous articles in The Daily Beast, a book by Michael Weiss and Hassan Hassan, and a recent story by The Washington Post’s Liz Sly have all attempted to demystify ISIS’s seemingly sudden growth by explaining it in organizational rather than religious terms.

Haji Bakr’s powerful role inside ISIS is not a new revelation. It has been reported in the past by ISIS defectors, leakers seeking to expose the group’s secrets, and in research papers analyzing the group. But the new ISIS documents and Der Spiegel reporting significantly advance the understanding of how Bakr engineered ISIS’s surveillance state and developed its intelligence apparatus.

Still, essential questions remain about the relationship between ISIS’s religious leaders and backroom powerbrokers like Bakr: Are there still distinct factions in ISIS’s leadership, with Baathist and religious factions coexisting? If so, who is in control, and does the weaker party understand its position? If these differences are no longer salient, how were they dissolved or by whom?

The influential position of ex-Baathists like Haji Bakr does not mean, ipso facto, that ISIS’s religious rhetoric is only a cynical ruse. Nor does it prove that Baathists are still secretly pulling the strings inside ISIS. Long before the group took its current form and declared a caliphate, it existed in various guises for more than a decade. Throughout those permutations, the religious, jihadist strain has been a constant. The surge of ex-Saddam officials entering ISIS or assisting it may have profoundly transformed the terrorist organization and given it the level of technical sophistication necessary to become a proto-state. But there’s no clear evidence yet that absorption of Baathists changed the fundamental ideology, as opposed to the tactical thinking, that has animated ISIS since its inception in 1999 under the name Jama’at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad.

Baathist expertise may provide some of the distinctive features separating ISIS from other jihadist groups. Yet another of ISIS’s qualities is perhaps most unique and less easily attributed to former Saddam officials: its populist appeal. There is something powerful enough in ISIS’s religious message and its approach to spreading that message that terrorist groups and individual supporters all over the world have pledged their loyalty to its self-proclaimed caliph, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

The texts governing ISIS are not Baathist ones penned by thinkers like the Syrian intellectual Michel Aflaq, who amalgamated Arab nationalism, Arab socialism, and pan-Arabism. Bakr may have provided the blueprint for how to set up the security apparatus for the caliphate and how to police it, but the overall revolutionary strategy comes from jihadist thinkers and from apocalyptic texts like “A Call to a Global Islamic Resistance” by Abu Musab al Suri.

Or the 2004 book The Management of Savagery by Islamist strategist Abu Bakr Naji. That text, posted on the Internet, outlines a populist strategy for jihadists to manipulate and manage religious and nationalist resentment—and to use harsh violence—in order to shape the circumstances allowing a caliphate to rise.

For the Baathists the battle is for Sunni power, a pushback on an American-engineered political settlement that left the Shia with political control in Iraq. For the true believers the fight in the Levant is an apocalyptic battle between good and evil. “The logic of ISIS is heavily influenced by its understanding of prophecy,” argue authors Jessica Stern and J.M. Berger in their new book on ISIS. For the time being those programs are aligned.

Former Saddam military officers occupy many of the government positions in the caliphate, but a shadowy group of jihadists around al-Baghdadi appears to wield final authority.

The marrying of the intelligence and administrative expertise of Saddam’s nationalist Baathists like Bakr with the true-believing jihadists of al-Baghdadi has made ISIS what it is today—a formidable force that will be hard to dislodge. But that alliance between secularists and jihadists, along with the partnerships with local Sunni tribes the Baathists helped shape, holds the seeds for ISIS’s downfall, too. This isn’t a marriage of love but of cold, hard convenience.

And it isn’t a tension-free one. In recent weeks among the disparate groups of the jihadi-led Sunni Muslim insurgency, signs have increased of disputes and disagreements. Recent jihadi abductions of Iraqi Christians have prompted disapproval among some of ISIS’s Baathist allies, some of whom are Christians themselves. U.S. and Iraqi officials argue that as ISIS suffers military setbacks, inherent contradictions within the alliances will surface more sharply among Baathists, tribes, and jihadist true believers.

The possible death last week in Iraq of former Iraqi general and Saddam adviser Izzat Ibrahim al Douri has prompted some Iraqi officials to predict that the Army of the Men of the Naqshbandi Order, Jaysh Rijāl aṭ-Ṭarīqa an-Naqshabandiya (JTRN), a powerful militia he commanded, may now fragment, with some fighters breaking with ISIS.

Yet ISIS has proved more durable than many imagined, despite the tensions and seemingly irreconcilable factions within the group. “After the liberation of Baghdad, the Islamic State will be finished,” an Iraqi ISIS supporter who allied with the group despite not sharing its religious convictions told The Daily Beast last July, less than a month after the capture of Mosul. He was confident then that the caliphate was only the means to an end: namely, restoring Sunni power in Iraq. Nearly a year later the caliphate endures.

Though war threatens to destroy the nascent state, it also provides a powerful force keeping ISIS together. As Shia militias appear to spearhead Iraq’s military campaign and some are accused of war crimes, the sectarian narrative and powerful Sunni chauvinism that led some Iraqis to support ISIS despite reservations about the caliphate’s religious program have been reinforced. War in Syria provided ISIS with the opportunity to expand and implement Haji Bakr’s security strategy. The ongoing war in Iraq conceals internal divisions by focusing efforts on an external enemy.