Irate New York State residents, including a state senator and an assemblyman, are calling for the renaming of Donald J. Trump State Park, in Yorktown Heights. With his recent remarks about Mexicans and Muslims, Trump “has shown himself to be a bigot,” said the creator of an online petition urging the name change.

Just a few miles further up the Taconic State Parkway, however, is another state park named after a public figure who made disparaging remarks about various minority groups.

This other gentleman once complained to an interviewer that “the foreign elements” were failing to “conform to the manners and the customs” of most Americans. He believed the kind of immigrants that would benefit America would be Europeans with “blood of the right sort.” He warned that “the mingling of white with oriental blood on an extensive scale is harmful to our future citizenship.”

He also boasted that he helped bring about a quota on Jewish students admitted to Harvard; he worried about Jews “overcrowding the professions”; and he was convinced that “the best way to settle the Jewish question essentially is to spread the Jews thin all over the world.”

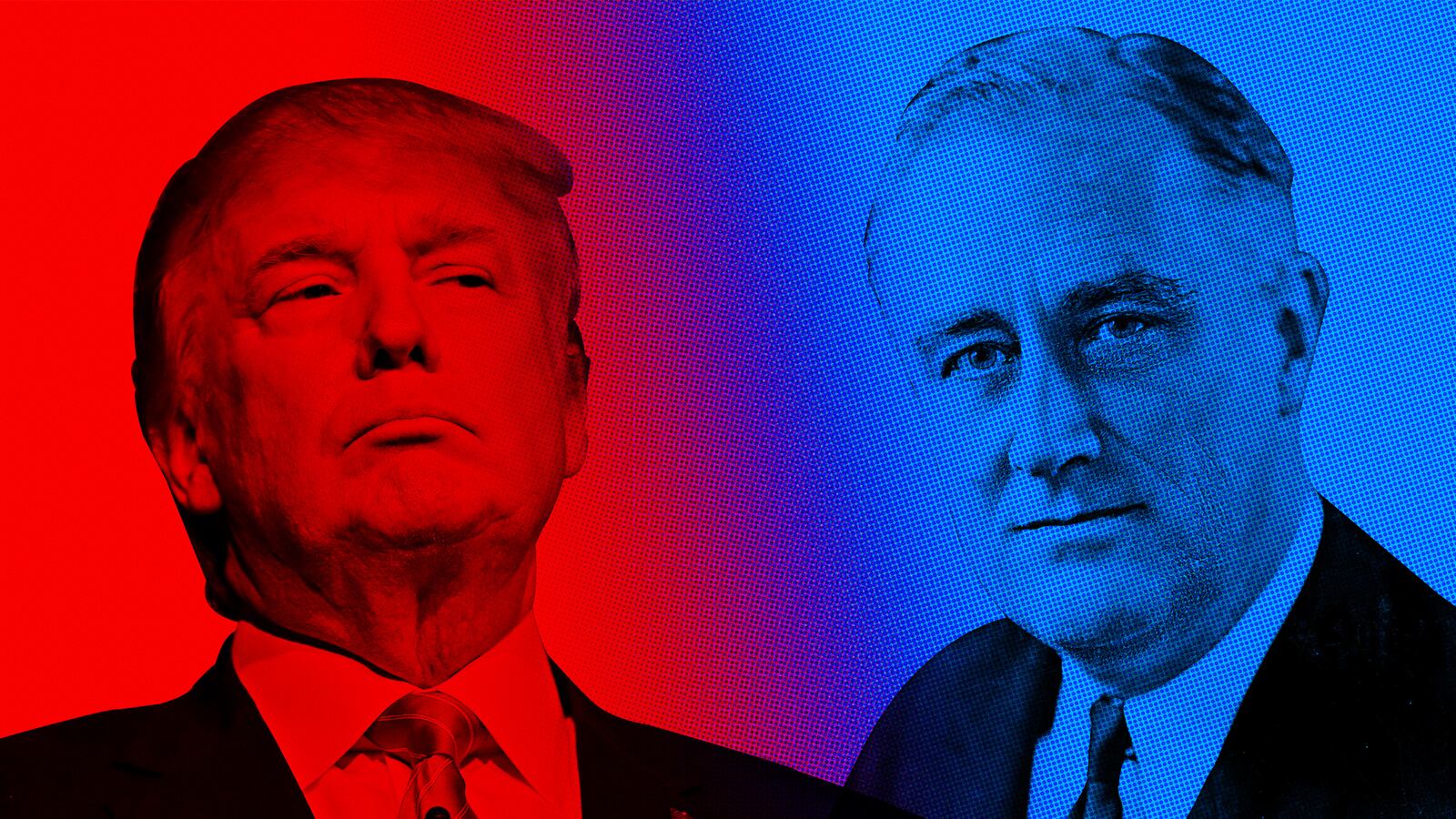

These may be the kind of sentiments many would imagine to have been expressed by Donald Trump, but in fact they were uttered by Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 32nd president of the United States.

It goes without saying that the differences between the two men are vast. It is a monumental understatement to note that FDR’s accomplishments as president dwarf Trump’s achievements as a real estate developer and entertainer. Yet in their attitudes toward foreigners and immigration, they had more in common than is generally realized.

Like many upper-class white Protestants of his time, FDR harbored a strong disdain for most immigrants—except for those with “blood of the right sort,” as he put it in a newspaper column he wrote in 1925. He advocated restricting immigration for “a good many years to come” and limiting subsequent immigration to those who could be most quickly and easily assimilated. How different is that from what Mr. Trump is currently advocating?

Roosevelt was deeply suspicious of Japanese immigrants. They “are not capable of assimilation into the American population,” he wrote in another 1925 column. “Anyone who has traveled in the Far East knows that the mingling of Asiatic blood with European or American blood produces, in nine cases out of ten, the most unfortunate results.”

These remarks were not some youthful indiscretion on FDR’s part. He was already a mature public figure and a rising political star, having served as a New York State Senator, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, and the Democrats’ 1920 vice presidential nominee.

Nor could FDR’s statements be chalked up to off-color humor, although he did indulge in his share of that. Presidential secretary William D. Hassett wrote in his diary of Roosevelt telling a joke that described the Japanese people as the offspring of an ancient union between humans and baboons. FDR’s grandson, Curtis Roosevelt, recalled that the president “would tell mildly anti-Semitic stories in the White House,” in which “the protagonists were always Lower East Side Jews with heavy accents.” Sometimes humor can be very revealing.

Roosevelt did not keep a diary or tape-record his Oval Office conversations, as some later presidents did. What we know of his private views of Jews comes mostly from third parties who were friendly to FDR and did not expect his statements to be made public.

For example, it was FDR’s friend, U.S. Senator Pat Harrison (who helped clinch the nomination of Roosevelt at the 1932 Democratic convention), who noted the president’s use of the phrase “dirty Jewish trick” to characterize a tax maneuver by the owners of the New York Times in 1937.

It was the era’s most prominent Jewish leader (and FDR stalwart), Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, who privately recounted a 1938 conversation in which the president alleged that Jewish domination of Poland’s economy was the cause of Polish anti-Semitism.

U.S. Senator Burton Wheeler, a Roosevelt friend and political ally, jotted down a remark that FDR made to him in 1939: “You and I, Burt, are old English and Dutch stock—we know there is no Jewish blood in our veins, but a lot of [other] people do not know whether there is Jewish blood in their veins or not.” Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr., privately noted (in 1941) FDR’s aforementioned statement about restricting the admission of Jews to Harvard.

And Vice President Henry Wallace’s diary is the source of President Roosevelt’s statement (in 1943) about “spreading the Jews thin all over the world.” Admitting no more than “four or five Jewish families” in each community would be best, Wallace reported the president as recommending.

Some will point out that such sentiments about Asians and Jews were common in those days. But what makes Roosevelt’s remarks particularly alarming is the likelihood that they played a role in some of his policy decisions.

FDR had no compunctions about herding more than 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry—most of them American citizens—into detention camps in 1942, in part because of his deeply-held belief that persons of Japanese ancestry were inherently untrustworthy and dangerous. (Asked by Time magazine if he would have supported the internment of the Japanese, Trump hedged: “I certainly hate the concept of it. But I would have had to be there at the time to give you a proper answer.”)

Roosevelt’s policy of turning away European Jewish refugees who were seeking haven from Hitler—during years when the U.S. quota for German immigrants was only 25 percent filled—likely was based to some degree on his personal conviction that having too many Jews in the country could lead to them having undue influence.

The president gave full expression to this perspective during a session of the 1943 Casablanca Conference. He remarked that Jewish residents of Allied-liberated regions of North Africa should not be allowed to “overcrowd the professions,” because that could lead to the same kind of “understandable complaints which the Germans bore towards the Jews in Germany, namely, that while they represented a small part of the population, over fifty percent of the lawyers, doctors, school teachers, college professors, etc, in Germany, were Jews.” (Roosevelt’s statistics were, of course, wildly inflated.)

All of which brings us back to the question at hand: Should public sites bear the names of individuals whose views on some subjects are abhorrent? If their records include some deeds that were admirable and others that were not, how should one be weighed against the other? Should we take into consideration the fact that FDR’s views probably influenced government policy and affected people’s lives, while Trump’s are (at least for now) just bombastic rhetoric?

In a different world, the names Donald J. Trump and Franklin D. Roosevelt might not be thought of in the same sentence. But if motorists on the Taconic State Parkway are mortified when they pass the exit sign for Donald J. Trump State Park, perhaps they should think twice when, moments later, they pass the sign for Franklin D. Roosevelt State Park. Sadly, the two men had more in common than most people realize.

Dr. Rafael Medoff is the founding director of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies and author of 16 books on Jewish history and the Holocaust.