In 1969, I was a young reporter living in New York, covering the city for the Boston Globe. My husband was a disc jockey on the primo FM rock station. They'd been running ads for a 3-day festival of “Peace and Music.” But there’d been other festivals that year, with many of the same musicians, and they’d drawn crowds of 50-70,000. No one we knew expected that Woodstock would be anything different.

The Friday it began, we were hosting a dinner party, but at 9 p.m., I got a call from Myra Friedman, who did publicity for Janis Joplin and The Band and was at Woodstock with them. "You've got to get up here!" she shouted. "It's fantastic. There’s half a million kids here. Never seen anything like it.”

How would I get there? We'd heard that all roads leading to the festival were blocked, with people abandoning their cars to hike 10 or 15 miles to the site. Myra said, "You can drive to Liberty—that road is clear. Come to the Holiday Inn, where all the performers are staying, and we'll get you over to the festival.”

At 8 a.m. the next morning, I jumped into my black VW Beetle and drove to the Holiday Inn, where Janis Joplin was in the bar, yelling, “Hiya honey,” to everyone. Nothing was happening on schedule. The organizers had hired limos to shuttle performers to the site, 20 miles away. But the limos couldn't get there. All the roads were jammed with cars left helter-skelter, as if they'd been dropped from the sky by a salt shaker. By Saturday, though, they'd devised a system: they would form a caravan of limos with police escorts, and break trails to get to the site.

When the next caravan was forming, Myra jumped into my Beetle and we cut into the middle of the limo line. If anyone waved or shouted for us to get away, Myra yelled back. We took off with sirens blaring and red lights flashing. It was comical: police car, limo, limo, small black Beetle, limo, limo. We drove across fields, over dirt roads and private driveways, and then we had to drive through the masses crushed together in a big grassy crater. The crowds parted like the Red Sea, but I was terrified I'd hit someone.

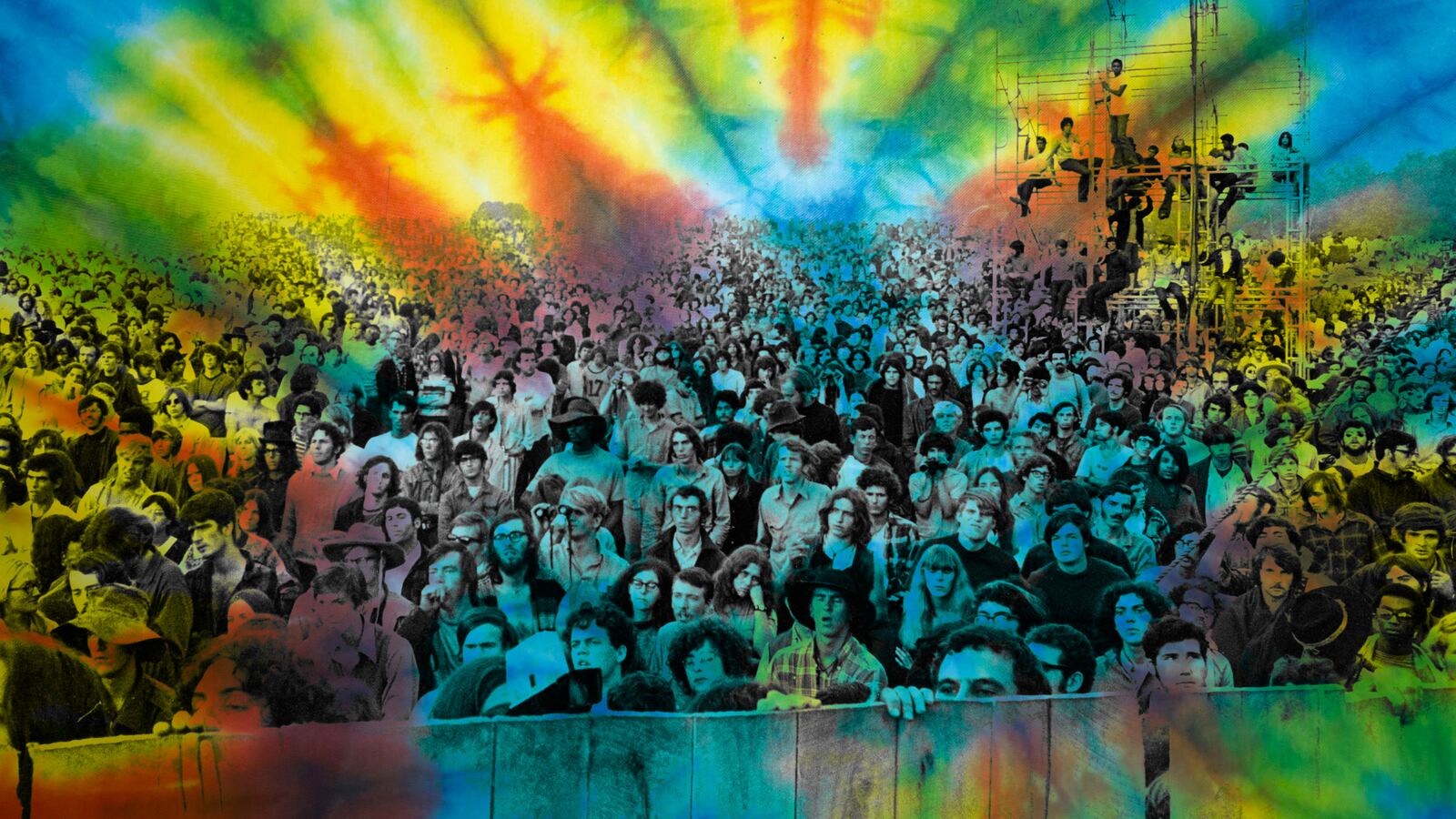

I walked out among the crowd; near the stage they were packed so tightly you had to shove your way through human walls. Farther back the crowd began to thin, and at the very back, there were campsites, psychedelic buses, and the Hog Farm commune offering free food. The crater had turned into a city made up entirely of youths. No one was in charge. It was anarchy, an outlaw gulch. Kids could smoke or ingest anything they wanted, take off their clothes, swim naked…. whatever.

"Closeup still life of three single-day admission tickets for the Woodstock Music and Arts Fair in Bethel, New York."

Blank Archives/GettyIt’s hard to really grasp the size of the crowd. The largest football stadiums in America hold about 100,000. Well, Woodstock had five times that many. Kids had started arriving the week before, and by Friday they’d trampled down the cyclone fences, so it became a free event.

Shortly after dark, a volunteer had announced, "The organizers didn't plan for this many people! We have shortages of food, water, and latrines. So it's up to us. Look around—these people are your brothers and sisters. So treat every person here like they really are your brothers and sisters. Share, take care of each other. That's the way we'll get through this.”

A medical tent was set up with volunteer doctors. Kids freaking out on acid would come in yelling, “I’ve been poisoned!” and others would talk them down. When they recovered, they were asked to stay and do the same for the next ones freaking out. Dr. William Abruzzi, the medical director, said at the end of the festival that his staff did not treat “one single knife wound or black eye or laceration that was inflicted by another human being.” No one saw a single fight.

Nature, however, did not cooperate. There was lightning that threatened the electric equipment and two torrential rainstorms, which turned the crater into a sea of mud. But most of the people rolled with it. They took off their wet clothes and washed themselves off in the lake. One group created a slip ’n’ slide track. They’d run and jump, chest first, into the mud, seeing who could slide farthest.

I suspect one reason for the prevailing sense of joy and generosity was that the drug of choice was marijuana, not alcohol. A local farmer said, "If marijuana makes people this gentle, it should be distributed free by the government.” The county sheriff said, “I never met a nicer bunch of kids in my life. When our cars got stuck in the mud, they helped push us out.”

The music ran all night: Janis Joplin, the Grateful Dead, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Santana, Sly and the Family Stone, The Who, and when the sun rose, Grace Slick of Jefferson Airplane announced, “Believe me: this is the new dawn.”

I don’t know how or when I got home. I remember driving my black Beetle out through the tight-packed crowds. This time, though, without police escorts, I was tense and anxious, the Beetle crawling forward as I waited for people in front of the bumper to move aside. The only other memory I have is that I was nearly out of gas, but all the gas stations in a 60-mile radius were closed. Pulling into one, I inserted a hose into my gas tank, pulled the lever so whatever gas was left in the hose would trickle in. I did this four or five times at different pumps, until I had enough to reach a station that was open.

But that’s it. I don’t remember where I spent the night. When I looked for details about going to Woodstock in Loose Change, my book about three women growing up in the Sixties, I was surprised to read this: “The bodies were packed so close and the smell—rotting fruit, urine, sweat, incense!—was so strong I thought I would faint and be trampled. It was not until dark that I was exhausted and stoned enough to enjoy the music.”

Leaving Sunday, I missed a signature moment of the festival: Jimi Hendrix on Monday morning, closing the festival with a weird, screechy, brilliant rendition of the “Star Spangled Banner.” Both Jimi and Janis Joplin would be dead from overdoses the following year, at age 27. This prompted Jacob Brackman, film critic for Esquire, to write in The New York Times, “It feels as if a great many of us have been overdosing, in one way or another; as if it’s nip and tuck who’ll make it into his thirties intact.”

As people began straggling home, when asked what the highlight of the festival was, they said the same thing: “the people.” They did not talk about the music, which was sensational, on a level no one had heard before. They spoke about the instant intimacy they’d felt with people they met, and the validation of who they were and their ideals.

This was not a gathering of hippies, radicals, and crazies. They were the children of mainstream America, caught in a generation-wide clash with their parents. The parents did not like their hair, their clothes, their drugs, their sexuality, their politics, and their questioning of everything.

An 18-year-old from New Jersey, who was hiking out Sunday with a muddy orange sleeping bag on his back, said the most important part of the festival was “being here with people like me. I guess it will reinforce my lifestyle, my beliefs, from the attacks of my parents and their generation.”

So many households were fractured. When I was studying at Berkeley, it was painful to be home with my parents. I was taking part in civil rights marches in San Francisco, picketing the Sheraton Palace for discriminating against Negroes (as they were called then), and my parents were realtors, worried and resentful about Negroes moving into white neighborhoods.

My father said Jews had faced discrimination when they immigrated here. “We pulled ourselves up by our bootstraps,” he said. “We didn’t ask for any special treatment.”

I’d developed a friendship with a black assistant professor, Albert Johnson, who’d studied at Oxford, was brilliant and charismatic, and was a personal friend of Federico Fellini. He was visiting L.A., where we lived, and when I asked my mother if we could invite him for brunch, she was flummoxed. “Who else could I invite?” she asked.

At Woodstock, kids were connecting with others having the same struggles with their families. And they were walking their talk. Left to their own devices, they’d created a community governed not by laws and rules but “peace and love.” As Grace Slick announced, “It’s the new dawn.”

So it seemed; this was now the Woodstock Generation, and you didn’t need to have been there to feel part of it. Joni Mitchell was not at Woodstock; her managers had scheduled her for the Dick Cavett show that Friday night, believing it was more important than performing at a festival. When she heard about it from friends, she wrote the iconic song, “Woodstock,” using the plural, we: “When we finally got to Woodstock…” The name came to stand for everyone in the generation, and we felt certain that, by our sheer numbers, we could move the world.

So why did it turn out to be a false dawn? Four months later, when the Rolling Stones gave a free concert at the Altamont Raceway in California, Hell’s Angels kept people away from the stage by beating them with pool cues. While the Stones were singing, “Under My Thumb,” an African-American man, Meredith Hunter, brandished a gun and was stabbed to death. Some attributed this disaster to the hiring of an outlaw motorcycle gang to serve as bodyguards for the Stones. The Stones embraced a demonic image—“Sympathy for the Devil”—and, unlike at Woodstock, the crowd was aggressive, shoving and tussling with each other.

The three days of Woodstock turned out to be a bubble in time, never repeated. While the festival was taking place, history was moving in a different direction. There were currents gathering force, unseen as yet. Hunter Thompson wrote in 1971 in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: “Every now and then the energy of a whole generation comes to a head in a long fine flash.” He thought, as many did, we were riding the crest of “a high and beautiful wave,” that would roll from sea to shining sea. We did not sense that if Woodstock was the crest of the wave, it would crash, as all waves do, pulling back with an undertow. The year before, Richard Nixon had been elected president and begun the inevitable backward roll.

We also did not sense the uniqueness of the music produced during that era and played at Woodstock. In my opinion, the outpouring and quality of songs—by the Beatles alone, who wrote 207 songs, plus Bob Dylan, who wrote 458, plus the Rolling Stones, Joni Mitchell, the Mamas and Papas, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, and dozens of others—has not been equaled at any other time in our lives. As a friend, Charles Horowitz, who was not at Woodstock, said recently, “The music lives on and on, for me and many of us.”

It’s notable that, thus far, the music has been more durable than the ideals of peace and love, of oneness and caring for our neighbors. One can only hope that the great pendulum of history will reverse direction again. Could the seeds of love and peace, now underground, be germinating, gathering momentum to blossom again?

Sara Davidson is The New York Times best-selling author of Loose Change, Leap! and Joan: Forty Years of Love, Loss and Friendship with Joan Didion. www.saradavidson.com