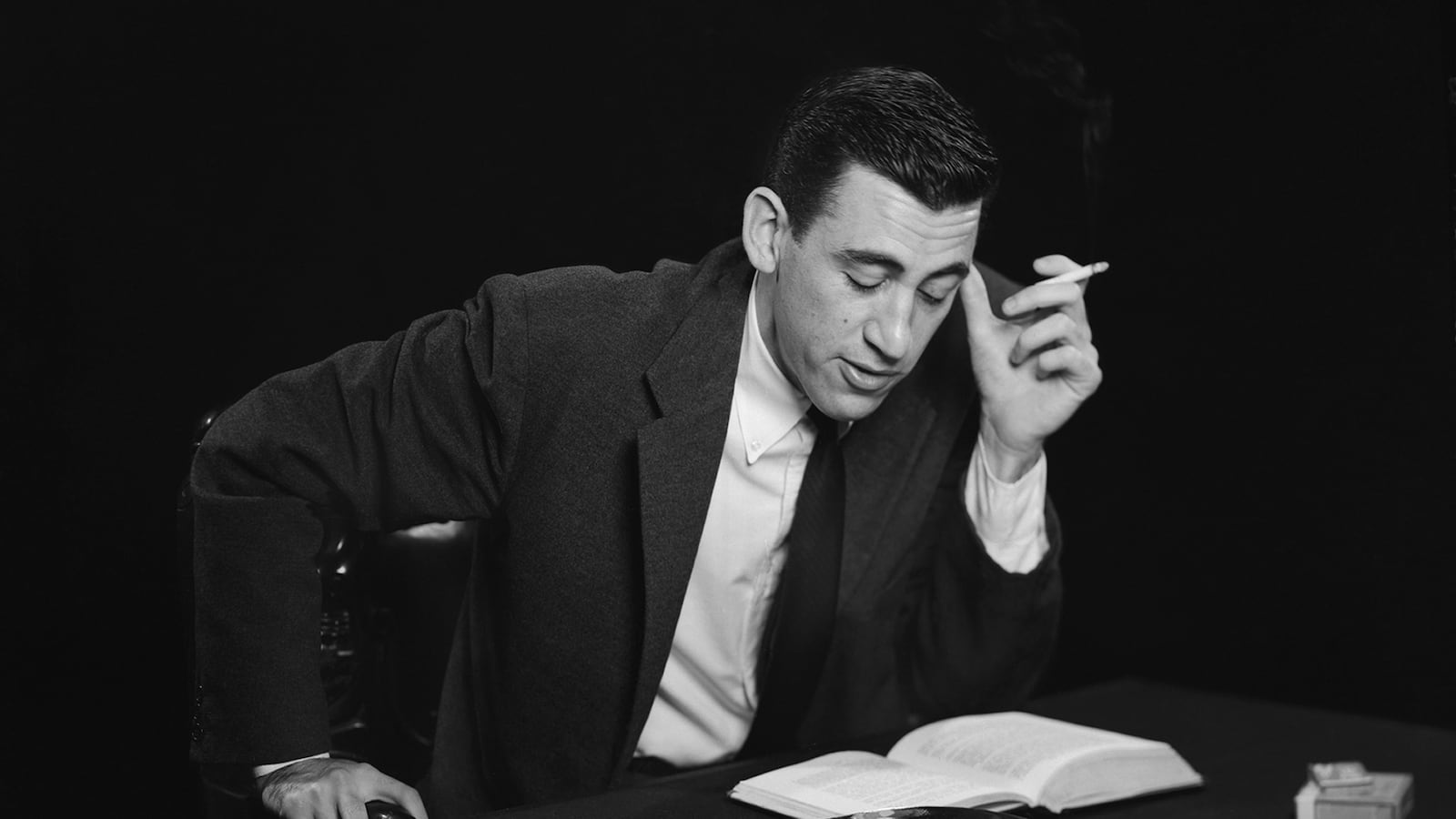

On the last day of May 1959 The New Yorker printed a story—or, more precisely, a novella-length cri de coeur—called “Seymour: An Introduction.” It was the first new work by J.D. Salinger to appear in the magazine, or anywhere else, in more than two years, and it wound up being the second-to-last thing Salinger published before his death in 2010, five decades later. By 1959, Salinger had long since retreated, both physically and psychically, to Cornish, New Hampshire, becoming in the process America’s most notorious literary recluse—a title he would retain for the rest of his life, despite Thomas Pynchon’s plucky efforts to dethrone him.

In “Seymour,” Salinger attempted, or claimed to be attempting, a portrait of Seymour Glass, the screwy, spiritual, and eventually suicidal elder brother of Salinger’s “alter-ego and collaborator,” Buddy Glass. At one point, Buddy, the narrator, reveals that he has been “sitting” on a “loose-leaf notebook inhabited by a hundred and eighty-four short poems that my brother wrote during the last three years of his life,” and that he, Buddy, plans sooner or later to publish these poems, which will prove that Seymour was one of America’s “three or four very nearly nonexpendable poets.”

What comes next is a bit mind bending—a glimmer of autobiography disguised as fictional prognostication. Even now, Buddy writes, “a good many young English Department people”—fans of his novels and stories—“already know where I live, hole up; I have their tire tracks in my rose beds to prove it.” Once Seymour’s posthumous poems materialize in print, he predicts, even more “matriculating young men and women will strike out, in singlets and twosomes, notebooks at the ready, for my somewhat creaking front door.”

The reason is simple: readers are inevitably attracted, Buddy explains, “to those few or many details of a poet’s life that may be defined here loosely, operationally, as lurid,” and they “respond with a special impetus, a zing, even, in some cases to artists and poets who as well as having a reputation for producing great or fine art have something garishly Wrong with them as persons.” He proceeds to list some examples: “extreme self-centeredness, marital infidelity, stone-deafness, stone-blindness, a terrible thirst, a mortally bad cough, a soft spot for prostitutes, a partiality for grand-scale adultery or incest, a certified or uncertified weakness for opium or sodomy, and so on, God have mercy on the lonely bastards.”

Anyone reading this passage in 1959 would have known that Buddy was referring to Seymour’s suicide, which was, in Buddy’s view, the spectacular flaw destined to transform Seymour’s readers into Buddy’s stalkers. Anyone with a working cerebellum would have also sensed that Salinger was alluding to his own reclusiveness, too, and to the seekers who were already striking out for his somewhat creaking front door. What no one knew in 1959 was just how prescient Salinger’s penultimate story would suddenly sound right now, in September 2013.

As you may have heard, a new documentary called Salinger by Shane Salerno has just “landed” in theaters. An oral biography of the same name, by Salerno and David Shields, is currently available at a bookstore near you. Both products, book and movie, have been loudly purporting to tell us—on the Today show, in The New York Times, on billboards and buses and perhaps even the backs of cereal boxes—what exactly was Wrong with Salinger as a person. And Buddy Glass was right: a good many of us have been responding to these so-called revelations with a special impetus. A zing. Myself included.

***

Late last month, my editor sent me one of the few advance press copies of Salerno and Shield’s 699-page oral biography. (The principals, hoping to maintain a profitable aura of mystery, weren’t screening the documentary for critics, either.) I read the entire brick of a book in two days flat. In part my motivation was professional: The Daily Beast had asked me to extract the pulpiest bits and file a quick cheat sheet. But my speed-read was also personal. I’d always wanted to know, as the movie’s marketing materials put it, What Happened to J.D. Salinger.

Twenty-four hours later, I dutifully submitted my story. Salinger was missing a testicle! Salinger married a Gestapo informer! Salinger was bad at poker! Et cetera.

The whole exercise seemed somewhat hollow, though, because for all the book’s “revelations”—some real, some reheated—and despite Salerno and Shield’s breathless attempts to explain What Happened to their subject—“the war broke him as a man and made him a great artist; religion offered him postwar spiritual solace and killed his art”—I didn’t actually feel like I knew Salinger any better after reading Salinger. Michiko Kakutani was right when she noted in her New York Times review that Salerno and Shields’s “choral, Rashomon-like portrait of Salinger” does not sift “fact from conjecture,” making for a “loosey-goosey, Internet-age narrative with diminished authorial responsibility.” The documentary was the same. I came away from it with a good idea of how much the actor Edward Norton loves The Catcher in the Rye (a lot), but I still didn’t have a handle on what Salinger was like.

So I decided to read something else instead. Scratch that. I didn’t decide: I gravitated, half-consciously, toward another, more primary source, the way you tend to do when you’re immersed in any biography, really, but especially a biography with a subject as recessive as Salerno and Shields’s.

What I read, or reread, in the days after finishing Salinger was Salinger’s Glass stories, a series about seven Upper West Side sibling geniuses, half-Jewish, half-Irish, the progeny of a team of vaudevillians, that began in January 1948 with the publication of “A Perfect Day for Bananafish,” a spare account of Seymour’s suicide, then gained momentum until it seemed to be the only thing Salinger was working on. By the time Franny and Zooey, a pairing of two earlier New Yorker stories about the youngest Glass siblings, appeared in 1961, Salinger was writing on the inner flap that the Glass tales were “a long-term project, patently an ambitious one,” with “some new material ... scheduled to appear [in The New Yorker] soon” and a “great deal” of additional “thoroughly unscheduled material on paper.” He added that he had “fairly decent, monomaniacal plans to finish [the project] with due care and all-available skill.”

Famously, Salinger would publish only a single new piece of Glass-iana, “Hapworth 16, 1924,” a long, strange story in the form of a letter from camp written by Seymour when he was 7, before vanishing from print altogether in 1965. But if Salerno and Shields are correct—and this is one of their real revelations—then five new Glass stories, all of them, like “Hapworth,” focused on Seymour, are set to be released sometime between 2015 and 2020. Four of the stories “explore the thirty years leading up to Seymour’s suicide and his lifelong quest for God,” including one in which “Seymour and Buddy are recruited at a party in 1926 for the children’s quiz show “It's a Wise Child.” The final story, meanwhile, “deals with Seymour’s life after death.” All of the new stories are narrated, like the old ones, by Buddy Glass.

When I started to reread Salinger’s Glass saga, my thinking was that there might be a more vivid place to find Salinger than in other people’s memories, and that maybe that place was the fictional world to which he was increasingly and then exclusively devoting himself in the years before, and now, apparently, after, he went silent. But what you find in the Glass stories isn’t just a better idea of what Salinger himself was like. You also start to sense What Happened to him after all: where he was heading when he left us, and why he went away.

***

It’s clear from the contemporaneous reviews and personal recollections cobbled together in Salinger that “A Perfect Day for Bananafish” wasn’t just Salinger’s first Glass story. It was also his first big smash.

“When Jerry published ‘A Perfect Day for Bananafish,’ it caused a great buzz,” says editor A.E. Hotchner. “Everybody was talking about it: ‘Did you read that story? Isn’t it remarkable? That little girl!’ He became a name to the intellectual set.”

“It seemed to be the first legitimate young American voice on the printed page that had all the power and song of what would later be in the words of Bobby Dylan, or the Beatles, or the music of Motown,” adds writer Gay Talese. “He was just the new man on the planet. And he carried us away.”

The story begins with Seymour’s superficial wife, Miriam, calling her superficial mother from a hotel in Florida, continues with Seymour joking, even flirting, with a 4-year-old girl named Sybil on the beach, and ends with Seymour shooting himself in the head as Miriam naps on the twin bed beside him. It is clean, precise, and devastating—nothing extraneous, nothing false—and it comes as close as any fiction I know to perfection.

Salinger’s next two Glass stories, “Uncle Wiggly in Connecticut” and “Down at the Dinghy,” were the same: polished, lapidary, indivisible. But then, in 1951, A Catcher in the Rye was published, and Salinger became a celebrity. Two years later, in 1953, he evacuated to Cornish and became a celebrity recluse.

By the time Franny and Zooey came out in 1961, followed by Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction in 1963, Salinger’s style had changed. Gone was the idiomatic cool, the chic minimalism, and the formal shapeliness of “Bananafish”; in its place was something shaggier, more digressive, more self-conscious, and more explicitly spiritual. Salinger remained as popular as ever with readers, who instantly snapped up every issue of The New Yorker that contained one of his stories and who always propelled his hardcovers to the top of the bestseller list. But the critics, evidently, were fed up.

Here’s how Janet Malcolm summarized the pummeling Salinger received in the early 1960s:

“Zooey” had already been pronounced “an interminable, an appallingly bad story,” by Maxwell Geismar and “a piece of shapeless self-indulgence” by George Steiner. Now Alfred Kazin, in an essay sardonically entitled “J.D. Salinger: ‘Everybody’s Favorite,’” set forth the terms on which Salinger would be relegated to the margins of literature for doting on the “horribly precocious” Glasses. “I am sorry to have to use the word ‘cute’ in respect to Salinger,” Kazin wrote, “but there is absolutely no other word that for me so accurately typifies the self-conscious charm and prankishness of his own writing and his extraordinary cherishing of his favorite Glass characters.”

Didion dismissed Franny and Zooey as “finally spurious, and what makes it spurious is Salinger’s tendency to flatter the essential triviality within each of his readers, his predilection for giving instructions for living. What gives the book its extremely potent appeal is precisely that it is self-help copy: it emerges finally as Positive Thinking for the upper middle classes, as Double Your Energy and Live Without Fatigue for Sarah Lawrence girls.”

Even kindly John Updike’s sadism was aroused. He mocked Salinger for his rendering of a character who is “just one of the remote millions coarse and foolish enough to be born outside the Glass family,” and charged Salinger with portraying the Glasses “not to particularize imaginary people but to instill in the reader a mood of blind worship, tinged with envy.”

The reviews of Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters were even worse—“merciless,” as David Shields, the co-author of Salinger, puts it. “‘Seymour: An Introduction’ is only a story by the most generous definition of the word,” wrote Orville Prescott. “Buddy rambles, digresses, pontificates, and fails completely to make Seymour Glass seem a believable human being.”

“I have just finished reading ‘Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters’ and ‘Seymour: An Introduction’ and should be interested in any evidence readers can provide that J.D. Salinger is still alive and writing,” added Jose de M. Platanopez.

“It is necessary to say that the four stories about the Glass family by J.D. Salinger, published in two books called Franny and Zooey and Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters, seem to have been written for high-school girls,” Norman Mailer concluded. “The second piece in the second book, called Seymour: An Introduction, must be the most slovenly portion of prose ever put out by an important American writer.”

The trouble with all of this is that when you read the latter-day Glass stories now, a half-century or so later, it’s obvious that Salinger’s critics were wrong. Not because the stories are great, although I think they are, but because neither Mailer nor any of his fellow travelers seemed to notice that Salinger was trying to accomplish something different from what he was after when the Glass series began in the late 1940s. He was past that now.

***

The most scathing, most representative takedown of the early 1960s was written by Mary McCarthy. “J.D. Salinger’s Closed Circuit,” which ran in the October 1962 issue of Harper’s, begins with a question—“Who is to inherit the mantle of Papa Hemingway?”—to which McCarthy immediately, scornfully replies: “Who if not J.D. Salinger?” This may have once been true: “Bananafish” glides across the page like a cold, chiseled iceberg. Seven eighths of the story is submerged.

But the style of “Zooey” and “Seymour,” the last stories Salinger wrote before “Hapworth,” couldn’t be more different from Hemingway’s, because Salinger’s point couldn’t be more different from Papa’s. This is what McCarthy & Co. were missing; they were still measuring Salinger by Hemingway’s old yardstick. Hemingway believed that the only sensible response to modern life was to withdraw into oneself, and he invented a prose style that reflected his theme: cool, plain, unadorned, and detached, with the author absent and surfaces, as apprehended by the five senses, in the spotlight.

And yet the solution that Salinger presents in the late Glass stories isn’t withdrawal or detachment. It is, in fact, the opposite of all that: encounter, as the critic Donald P. Costello once put it. At 22, Franny is in a funk because she’s “sick of pedants and conceited little tearer-downers” and “ego, ego, ego”—Holden Caulfield’s famous “phonies”—so her brother Zooey, 25, urges her to live out of love for everyone, because “there isn’t anyone out there who isn’t Seymour’s Fat Lady”—that is, “Christ Himself, buddy.” In “Seymour: An Introduction,” Buddy’s solution is the same: to return to teaching, as attractive as withdrawal might seem. “There is no single thing I do that is more important than going into that awful Room 307,” he writes, because “all we do our whole lives is go from one little piece of Holy Ground to the next.”

Like Hemingway, Salinger created a style that mirrored his theme: intimate, engaged, idiosyncratic, informal, garrulous, and convoluted, with the narrator always present on the page in the person of Buddy Glass. And far from being inadvertent—evidence, as various pundits argue in Salinger, that the author had “lost it,” “destroyed his art,” or “retreated so far into the bunker of his mind that he was writing for an audience of one”—this is a shift that Salinger was supremely conscious of. Far more so, in fact, than his critics. “I think it’s high time,” Buddy Glass writes in “Seymour,” “that all the elderly boy writers were asked to move along from the ballparks and bull rings.”

The proof is on the page. In his dedication to Franny and Zooey, Salinger describes himself as “hopelessly flamboyant.” In “Zooey,” Buddy calls his style “excruciatingly personal, and reprints a letter he characterizes as “virtually endless in length, over-written, teaching, repetitious, opinionated, remonstrative, condescending, embarrassing, and filled, to a surfeit, with affection”—a fairly complete summary of how critics would respond to the story itself when it eventually appeared in book form. Later, in “Seymour,” Buddy confesses that he is too “ecstatically happy a prose writer” to be “moderate or temperate or brief”—or “detached.” Structurally, the stories cease to be chronological narratives and become instead what Buddy describes as “prose home movies.” “I want to distribute mementos, amulets, I want to break out my wallet and pass around snapshots, I want to follow my nose,” he writes. “In this mood, I don’t dare go anywhere near the short-story form. It eats up fat little undetached writers like me whole.”

And just as Salinger was aware that Buddy’s style has “flaws”—“if the style is to communicate the love of a totally involved human being,” explains Costello, “it will not be neat or tidy or economical or cold or crisp”—he was also aware that his characters, Buddy included, could be irritating: that they could seem, as Gore Vidal once complained, like “this ghastly, self-observant family, going on and on about everything of importance to them, which they assume is important to all the world.” Janet Malcolm was right when she said that she didn’t “know of any other case where literary characters aroused such animosity, and where a writer of fiction has been so severely censured for failing the understand the offensiveness of his creations. In fact, Salinger understood the offensiveness of his creations perfectly well.” Buddy himself recalls, with a nod of self-awareness, that many quiz-show listeners considered the Glasses “a bunch of insufferably ‘superior’ little bastards that should have been drowned or gassed at birth.”

And so what you realize, reading the Glass stories today, is that in “Zooey” Salinger isn’t putting the title character on a pedestal; he isn’t “cherishing” Zooey, to quote Alfred Kazin’s putdown, or creating a “wise and loveable and simple” savant to show up all those “phonies” who weren’t lucky enough to be born Glasses themselves, to quote Mary McCarthy’s. He’s presenting Zooey as a flawed, arrogant young man who berates his mother when she invades his bathroom and browbeats his sister when she has a spiritual breakdown but is nonetheless groping, in endless, annoying, agonizingly realistic bouts of self-contradictory, smarty-pants dialogue, toward some sort of epiphany of encounter. It seems to me that’s who Salinger was, too.

In “Seymour: An Introduction,” meanwhile, this sense of identification—of Salinger himself being present in the prose—is even stronger. More than half the story consists of Buddy Glass clearing his throat, talking about himself, talking about writing, digressing, apologizing, anticipating the reader’s reservations, stopping, starting, and stopping again. This isn’t an accident; it isn’t “the mental acuity of Salinger … diminishing right in front of you,” as one of Salinger’s talking heads puts it. By the time Buddy begins to describe Seymour 67 pages in—his eyes, his ears, his nose, his clothes, his athleticism, or lack thereof—it begins to dawn on you that while the story is “supposed” to be a portrait of Seymour as elder brother and guru, it’s actually a self-portrait of the character who’s struggling to write Seymour back into existence: Buddy Glass himself. In this “Introduction,” Seymour never really materializes; it’s Buddy, as well as his old “alter-ego and collaborator,” to whom we’re being introduced.

“Seymour: An Introduction” enacts what is it. It performs the process of a writer writing. And so it’s still the closest we can get, I think, to understanding what Salinger was actually like—whatever the ads for Shane Salerno’s documentary might claim.

***

Given how grievously the critics of the early 1960s misunderstood Salinger’s new style—how far behind him they lagged, and how violently they lashed out—it isn’t hard to imagine why Salinger decided to disappear from print: he wanted to keep going in that direction and probably preferred not to have Norman Mailer second-guessing him along the way.

Up in Cornish, Salinger continued to hammer at his typewriter every day, and he filed his finished and unfinished manuscripts in a color-coded vault, according to eyewitnesses. In At Home in the World (1998), Salinger’s former girlfriend Joyce Maynard wrote that “he had compiled stacks of notes and notebooks concerning the habits and backgrounds of the Glasses—music they like, places they go, episodes in their history. Even the parts of their lives that he may not write about, he needs to know. He fills in the facts as diligently as a parent, keeping up to date with the scrapbooks.” One time Salinger told his friend Alastair Reed, the Scottish poet, “You know, the Glass family have been growing old just as you and I have.”

Likewise, it’s no surprise that Salinger intended to release his later work posthumously, as Salerno and Shields report. Buddy says as much in “Seymour”: “What is it I want (italics all mine) from a physical description of [Seymour]? … I want it to get to the magazine … I want to publish it … I always want to publish.”

The only surprise, I suppose, would be if the new Glass stories don’t turn out to be even more untidy and undetached and intimate, when they finally emerge from the vault, than the ones that preceded them in print.

So if you are tempted to see the Salinger documentary or read the Salinger book—if you feel that zing—by all means, go ahead. But don’t be fooled into thinking that you’re glimpsing the real J.D. Salinger up on that screen, or uncovering him in those loosey-goosey pages. My guess is that Salinger spent his last 45 years squirreling away something much richer and more revealing up in New Hampshire, and that we will discover far more of him in the continuing Glass chronicles, however “good” they may or may not be, than in any account of his Gestapo marriage, his single testicle, his poor poker face, and so on, God have mercy on the lonely bastard.