Elections

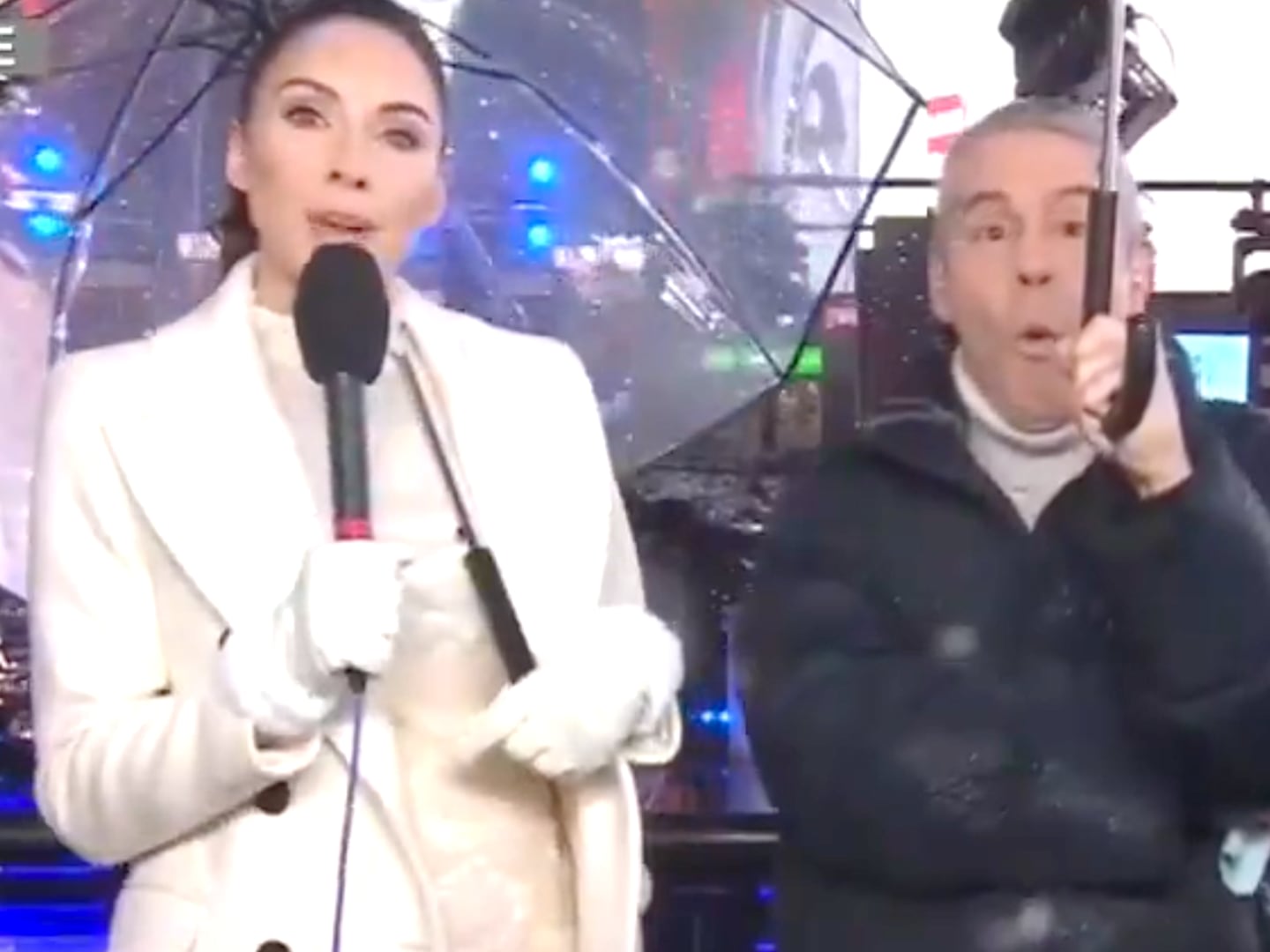

Photo Illustration by Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast/Getty

What’s the Main Reason Women Candidates Drop Out Early? Take One Gue$$

DECK STILL STACKED

A once-diverse field has winnowed to one that’s led by white men. And barriers to female candidates’ fund-raising is the leading culprit.

opinion