There’s a difference between journalism and voyeurism and, too often, Secrets of a Psychopath partakes in the latter.

The subject of director Derek Dillon’s three-part docuseries, premiering today on Sundance Now and AMC+, is the March 22, 2012, disappearance of Elaine O’Hara, a single Irish woman living on the outskirts of Dublin. O’Hara had dreams of becoming a Montessori school teacher and worked as a childcare assistant, but her professional aspirations were complicated by her considerable mental health issues, which included depression, anxiety, and borderline personality disorder. Those afflictions had led to a teenage suicide attempt and multiple stays in psychiatric hospitals, and were further exacerbated by the death of her mother. She was a loving and selfless individual, if also an unstable one. Consequently, when she vanished, many were quick to conclude that she had taken her own life by jumping off the cliffs near Shanganagh Cemetery, where—following her release from a psychiatric ward—she’d visited her mother’s grave with her father that day, and where her car was later found.

Still, things didn’t quite add up. Her iPhone was found in her apartment. Her car boasted a charger for a Nokia cellphone that she wasn’t known to own. And she’d been planning on volunteering at the Tall Ships’ Races the following day. It wouldn’t be until 13 months later that the truth would come into clearer view. On Sept. 10, 2013, anglers at the Vartry Reservoir in nearby Wicklow retrieved articles of clothing, yellow rope with handcuffs attached to it, leather restraints, head gear with a ball gag, and a zipper-mouth gimp mask from the water. Three days later, O’Hara’s skeletal remains were located in the Dublin Mountains near Kilakee. And then, a second search of the reservoir turned up O’Hara’s keys. As these amazing coincidences proved, this was a case of murder.

Further examination of O’Hara’s phones and computers revealed that the deceased had led a secret second life in the world of BDSM. Her laptop was full of images of mutilated bodies, naked and murdered women, serial killers, and herself (clothed and unclothed) being abused—as well as documents about “piquerism” (the sexual puncturing of skin with sharp objects) and a signed “slave agreement” contract. O’Hara apparently liked to assume the BDSM role of the submissive, and would suffer scarring physical wounds that she then showed off to those she knew. She also told acquaintances and colleagues that she was engaged in a scary relationship with a married man. CCTV footage soon corroborated this narrative, via images of a male arriving and departing her apartment while being careful to always shield his face from the cameras.

Who was this mystery man? In texts, O’Hara referred to him as “David,” and Secrets of a Psychopath depicts their unhealthy conversations via on-screen graphics. “My urge to rape, stab, kill is huge. You have to help me control or satisfy it,” he wrote at one point. “I want to stick my knife in flesh when I am sexually aroused. Blood turns me on. I’d like to stab a girl to death one day,” read another. His commentary was that of a sadistic predator, as well as a domineering sociopath, browbeating O’Hara into continuing a relationship that was predicated on him getting off (and thus satiating his bloodlust) by brutally binding and stabbing her—a practice that had taken place in her apartment, as proven by a mattress covered in knife marks, blood, and semen.

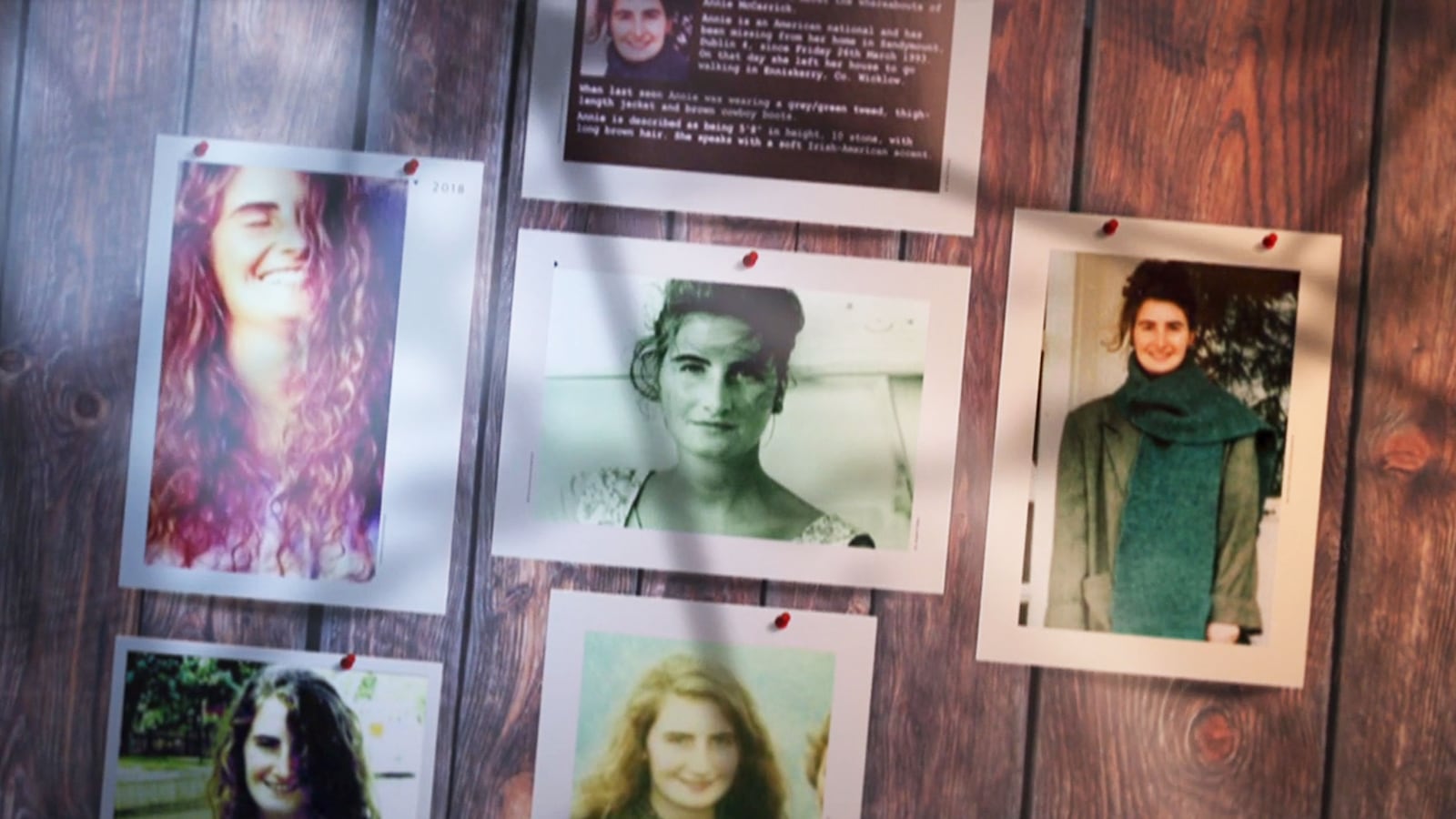

To its detriment, Secrets of a Psychopath paints this horrifying picture with almost no first-hand material; save for a handful of oft-seen photographs and a few blink-and-you’ll-miss-it news clips, it utilizes almost no archival video or audio. It also lacks the participation of O’Hara’s friends and relatives, or the many law enforcement members who carried out the investigation. What it does have is numerous reporters and criminologists who recount every detail of the case in exacting and breathless fashion, frequently to a monotonous degree. Even taking into account that it wants to get viewers back up to speed following commercial breaks (and at the start of each episode), the series sometimes feel like it’s rehashing in order to distend the proceedings to a full three chapters.

Worse, however, is the melodramatic cheesiness with which these people pronounce new developments, and the way those statements are accentuated by blaring momentous musical cues. To compensate for its dearth of first-hand accounts or intriguing archival evidence, Secrets of a Psychopath piles on the exaggerated sensationalism. That would be frustrating in any context, but what makes it more vexing here is that the series simultaneously exhibits a real interest in sympathetically understanding O’Hara. A troubled woman whose psychological problems made her vulnerable to her abuser’s manipulations, she was a lost soul in search of companionship and direction who found herself at the mercy of a madman—whom, it was ultimately determined through a canny analysis of cell phone tower pings, text-message clues, and astute cross-referencing of multimedia data, was Graham Dwyer, an unassuming architect with a wife and two young children.

Dwyer himself is a fascinating example of an everyman whose ordinary outward appearance masked his lethally deviant interior life. Again, though, Secrets of a Psychopath can only plumb the depths of his mind and heart from a distance, courtesy of commentary from various journalists and experts who not only had no contact with him, but weren’t even directly involved in the effort to identify and catch him. The prosecution of Dwyer eventually hinged on a plethora of circumstantial evidence, and Dillon’s series likewise tells its tale via second-hand reports that leave viewers at a remove, forced to comprehend O’Hara’s truly horrifying fate—and the quest to bring her killer to justice—through corny storytelling methods that are more reductive than enlightening.