Oscar Robertson, one of the greatest players in NBA history and a visionary labor rights leader, is riding out the current stretch of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic down in Florida. It’s not his permanent residence, but like many in the Sunshine State and across the globe, the 82-year-old is worried, Robertson told me in an August phone conversation. He’s been vaccinated, and is taking every precaution, including wearing a mask outdoors, until conditions improve. “Goodness, gracious,” he said. “It’s unbelievable, unbelievable.”

He was baffled to read that a number of pro football players were making a public show of refusing to get the jab. Beyond the spread of the new variant, the risks posed to children and family members, Robertson couldn’t comprehend why an athlete wouldn’t at a bare minimum be looking out for their teammates, regardless of what misinformation they’d been fed. “Why would a player say ‘I don’t want to get the shot’ if he's going to be around other players?” he plaintively asked. “Why would he do that?"

That Robertson would view the ongoing health crisis as requiring greater labor solidarity shouldn’t come as much of a surprise.

For all the Big O’s successes on court—the awards and accolades, the titles and medals won, his name scrawled at the top of the NBA’s record books, and the effusive praise from his contemporaries—Robertson’s legacy is also built on the decades spent fighting for justice and equity. He’s stood up to groaning bigots that treated him as less-than-human and threatened his life; he locked arms in solidarity in order to bring an All-Star game to a halt; and he dragged the NBA court and then testified before Congress, demanding that he and his in-demand, talented colleagues should (at a minimum) be able to choose their place of employment. All this was accomplished at a time when an outspoken athlete could easily find themselves on the unemployment line.

“There is a long tradition in our league going back to Oscar and others, including Bill Russell, who spoke out about civil rights issues,” Commissioner Adam Silver told Sports Illustrated’s Jack McCallum in 2020. “It’s a culture that’s been passed down from generation to generation, and Oscar led the fight.”

Over the summer, Robertson watched the Milwaukee Bucks win their first NBA title in 50 years, since he and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar last led the team to glory. It delighted him to no end. He marveled not just at the tens of thousands who had crammed into what the team dubbed “the Deer District” outside the stadium, but franchises now worth billions, and contracts for the biggest stars topping $200 million. As much as any NBA player, Robertson fought to ensure at least a somewhat more equitable distribution of wealth, though this stretch of NBA and labor history may have faded over time for fans and players alike.

“Some don’t know what the Oscar Robertson Rule is all about,” he said of the 1976 settlement agreement granting NBA players the right to free agency before any of the other major pro sports leagues. According to Robertson, those unaware of his battles should probably ask themselves, “How did it get this way?”

Born in 1938, Robertson grew up in poverty, first in rural Tennessee and then in a segregated housing project in Indianapolis, Indiana. Buying a regulation basketball was beyond the family’s means, but Robertson honed his skills as best he could, shooting tennis balls or crumpled cans at imaginary baskets before receiving a battered ball at age 11. Lack of proper equipment or not, his skills soon became evident.

As Robertson detailed in his 2003 autobiography, The Big O: My Life, My Times, My Game, athletic ability couldn’t shield him from the rampant racism of the era. He led Crispus Attucks High School to consecutive state championship-winning seasons in 1955 and 1956, becoming the first all-Black institution in the nation to do so. The prior year, Crispus Attucks fell to tiny, all-white Milan High School in the title game—an upset of such enormity it would be used as the basis for the movie Hoosiers. Annually, the state title winner would be feted with a parade in the heart of Indianapolis. When Milan High won, tens of thousands of fans lined the streets. Robertson’s team was shunted back into a predominantly Black part of town, thanks to the then-mayor, who feared the presence of that many Black athletes and fans would lead to violence.

“Even now I wonder: Did they think we’d riot because we were primitive animals, beasts who could do nothing but destroy?” Robertson wrote in his autobiography. “Or maybe, just maybe, did they worry because they knew we had good cause and were entitled to our rage?”

Former NBA players Yao Ming, Oscar Robertson and Bill Russell are honored by LeBron James #23 of the Cleveland Cavaliers and the Eastern Conference in the first half during the NBA All-Star Game 2016 at the Air Canada Centre on February 14, 2016 in Toronto, Ontario.

Elsa/Getty ImagesRobertson only agreed to participate in a ceremony retiring his high school jersey if his Crispus Attucks teammates were included. By his account, their groundbreaking achievement had never received the proper recognition. "Because it's a Black school, people just don’t care. Nobody cares about Black issues,” he said in 2009. (Six years later, Indianapolis righted the long-overdue wrong by bringing the team back to serve as honorary grand marshals.)

At the University of Cincinnati, Robertson continued to encounter deep-seated prejudices. Segregated drinking fountains and lunch counters were still the norm; during his sophomore year at a game in Houston, he was barred from staying at the same hotel as the all-white coaching staff; a letter from the Klu Klux Klan was delivered prior to a tournament in North Carolina, warning Robinson he’d be shot if he suited up. (He played anyway.) Someone left a black cat in the locker room when Cincinnati played the then-segregated North Texas State University. Once he stepped on court, Robertson was met with a deluge of racist jeers and pelted with food.

As the invectives rained down, Robertson stood perfectly still, refusing to warm up with his teammates, and seething with justifiable rage. “I’ll never forgive them,” he told the Indianapolis Star about his college years Still Robertson thrived. By graduation, he ranked as the all-time leading scorer in NCAA history, and then trekked to Rome for the 1960 Summer Olympic Games, winning a gold medal.

Robertson’s dominance continued after he was drafted by the Cincinnati Royals. (The team has since moved twice, first to Kansas City and now Sacramento.) Long before Russell Westbrook was racking up triple doubles, the dominant 6-5 floor general averaged over 30 points, 10 assists, and 10 rebounds per game over the first six years of his career. The twelve-time All-Star and 1964 MVP still ranks 10th and 3rd in points per game and assists per game, the only NBA player in league history to crack the top-20 in both categories. Before Michael Jordan’s ascendance, Robertson (or, occasionally, Jerry West) was invariably cited as the greatest guard the game had ever seen.

At the 1964 NBA All-Star game in Boston, the players saw an opportunity. At the time, the minimum NBA salary was only $7,500. Many players took a second job in the offseason. Prior to tipoff, Robertson, along with fellow luminaries Bill Russell and Jerry West, locked arms, refusing to play. They wanted the league to provide a guaranteed pension, a formal recognition of the nascent union, and seemingly basic amenities, like having a trainer on every coaching staff. The then-commissioner pleaded with the striking workers, and at least one owner stomped his feet, swearing they’d live to regret their act of defiance. “We thought that was just disrespectful,” Robertson said. No matter what threats were lobbed, Robertson and his cohorts wouldn’t budge.

The commissioner and owners blinked first. The players’ demands were met; the game went ahead as scheduled; and Robertson was named MVP. Within a year, Robertson became the president of the NBPA, the first Black man to reach such heights not just in sports, but any entertainment union.

Their victory didn’t mean basketball had moved out of the stone age. (Early in his career, unwritten racial quotas were adhered to by NBA teams.) A far greater battle loomed in Robertson’s near future: the landmark class-action lawsuit he headed: Robertson v. National Basketball Association. In 1970, the NBA was deep into negotiations on a merger with their fledgling competitors, the ABA. So the union filed an antitrust suit, stopping the two leagues from becoming one. Primarily, they wanted to have the same rights as every other laborer and be allowed to ply their trade once their contractual agreement had expired. As things stood, they were de facto tied to one employer for life. “Players were basically indentured servants to their teams,” Kareem Abdul-Jabbar wrote in a recent essay for Jacobin magazine.

Six years later, and two years after Robertson had retired, he won. Though true free agency was still years in the offing, the settlement agreement allowed players to negotiate their services to the highest bidder. Robertson believes that for a time, the NBA harbored a grudge. (Despite being feted with post-career honors, Robertson never found a way into a pro-level coaching role. His stint as a broadcaster for CBS was short lived, too.) Spearheading the case, “sort of left a bad taste in the NBA’s mouth,” Robertson told The Undefeated in 2017. “They might tell you it’s not true, but I’ve heard it from other guys around the league I played with and some after that. I think they really resented that, to be honest.”

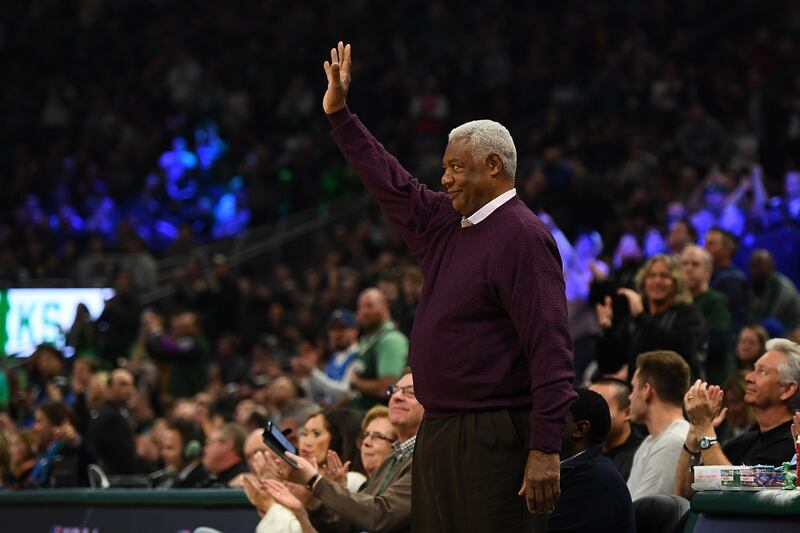

Former NBA player Oscar Robertson waves to the crowd during the first half of a game between the Milwaukee Bucks and the Philadelphia 76ers at Fiserv Forum on February 22, 2020 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Stacy Revere/Getty(During the discovery process of the trial, it was revealed that one owner called him an “adversary of the NBA,” and suggested ownership should have been allowed to pick a more suitable person for the job. )

Similarly, former All-Star guard Joe Caldwell sued the NBA over a withheld pension. For decades, Caldwell has insisted the NBA retaliated by blackballing him. Asked about Caldwell, Robertson backed up his claims. “I don’t doubt that one bit,” he said. “All of the player reps were in danger of being cut from the team, and that includes Oscar Robertson as well.”

Since his playing days ended, Robertson has continued to put his weight behind causes he believes in. He joined a 2011 lawsuit filed to block the NCAA from using the likenesses of college players without compensation, has backed pro-marijuana legalization campaigns in Ohio, and helped found a nonprofit dedicated to aiding players navigate their post-playing careers.

Throughout all the stories written about Robinson, both in the NBA in retirement, there is a constant throughline. He’s been described as “angry and bitter,” over the lack of recognition for his contributions, or a “perfectionist,” who’d berate and bully teammates. When Robertson left the Royals to join the Bucks in 1970, the right-wing Cincinnati Enquirer promised he’d “grow old a bitter man,” forever blaming others for his failings. Bill Simmons, the founder of Grantland and The Ringer, devoted chunks of his chapter on Robertson in The Book of Basketball to his glowering demeanor. (Asked about Simmons’ interpretation, Robertson said he’d never heard of him.)

When we spoke, none of the bellicosity came through. The message remained the same, but he was willing to temper his delivery. Robertson praised the brief wildcat strike the Bucks started during the bubble season in Disneyworld following the shooting of Jacob Blake, but understood why the players returned to the court. In terms of keeping the workforce safe, the whole endeavour was a success, he said. If modern fans didn’t rhapsodize about his dominance on court, well, that was understandable, too. He downplayed comments made in 2018 about white athletes not standing up for social justice, saying he understood why some needed time to find their voice. The problem, he explained, was that the question was being posed to Black athletes as a matter of course. For some, both Black and white, addressing these subjects takes time. Allowing people room to come around doesn’t obviate the necessity.

“I don't think you can be like a bug on the wall, and say, Oh, that's the way things are,” said Robertson. “A country has to grow up or it becomes stale.”

But given the life he’s lived and obstacles he’s overcome, it’s hard to imagine the kind of person who wouldn’t at times express some justified sense of resentment, if not outright anger. And perhaps someone willing to entirely turn the other cheek couldn’t have taken on an entire league, let alone prevailed.

As Robertson wrote in his autobiography, Larry Fleisher, the general counsel for the NBPA during the lawsuit, repeatedly told him: “I had the one great talent necessary for an effective labor negotiator: always distrust the other side.”