In late November of 1952, Oona O’Neill Chaplin, then a 27-year-old mother of four, flew from Europe to Los Angeles for a week-long visit to the house she and her husband had until recently called home. It wasn’t a pleasure trip. Oona was in town to wrap up their life in America and to recover her family’s fortune, the money her famous husband—Charlie Chaplin—had buried in the backyard.

According to a neighbor who recounted a conversation he had with Oona over a decade later, she took the recovered cash, went to a bank to convert the pile into thousand-dollar bills, and then sewed them into her mink coat, following her husband’s instructions. Ten days after her arrival, she slung her now very valuable mink over her arm, said a teary goodbye to her home country, and boarded a plane back to Europe.

“While the veracity of this particular story, like so many tales about the Chaplins, could be questioned, there is no doubt that Oona was a key figure in saving her husband’s assets and that had she not been up to the task, the bulk of the Chaplin fortune might have been lost,” Jane Scovell writes in the biography Oona: Living in Shadows.

For 38 years since the premier of his first film in 1914, Charlie Chaplin had been a fixture in Hollywood. His life story was quintessentially American: the rags to riches, the pulling-up of bootstraps, the embodying characters that became familiar in every U.S. home. Yet, Chaplin was not in fact an American. While he had lived in the States for decades, the British-born actor had never gotten his citizenship.

This fact might have saved him from the gravest fallout of the witch hunt that was McCarthyism and the blacklist that tore Hollywood apart in the middle of the 20th century, but it also had another sudden and startling effect. In September of 1952, Chaplin was effectively forced into exile by the U.S. government. From the day Chaplin left the shores of America, unaware of the decree about to come down on his head, to his death over two decades later, he only returned once to the country to which he had given so much of his life and talent.

Sixty-three-year-old Chaplin may have been a household name at the height of his career in 1952, but he was also no stranger to public opprobrium.

As a young Brit, the born performer bootstrapped his way to success, but he also followed the path of so many who suddenly find themselves enjoying fame and fortune. His dubious decisions, particularly in light of the accepted principles of the day, were plenty.

The moral police turned their noses up at his propensity for divorce. They wagged their tongues even more ferociously when newspapers began covering his involvement in a paternity lawsuit surrounding an illegitimate child nearly a decade before he was ousted from the country. (While a blood test would ultimately determine the baby was not his, he would still be ordered to pay child support.) And certainly, if Chaplin was to get into trouble for anything, it should have been twice marrying underage women (all of the mature age of 16), and only narrowly avoiding a third offense by waiting for his fourth wife, Oona, to turn 18 before they married against the wishes of her famous playwright father.

But in the late 1940s, it was the Cold War and the Red Scare at home that was on everyone’s minds. The biggest way this materialized in Hollywood was in the blacklist, the list of people banned from working in the entertainment industry under suspicion of communist sympathies. The most extreme form this took was the 1948 trial of the Hollywood Ten that ended in the imprisonment of 10 directors, screenwriters, and producers for refusing to cooperate with the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Chaplin had not been immune to the probe prior to his expulsion from the country. In 1948, his name was added to the FBI’s Security Index and he had been officially added to the Hollywood blacklist after his own failure to cooperate with a congressional inquiry. (Over the course of their surveillance and inquiry into Chaplin, the FBI built up a file thousands of pages long.)

While he wouldn’t name names or indulge the McCarthy fever, Chaplin did staunchly deny any connection to or affiliation with Communism. “I do not want to create any revolution, all I want to do is create a few more films. I might amuse people. I hope so,” he said.

Over the previous decade, some of Chaplin’s films had taken a more political tone. The Great Dictator in 1940, for example, lambasted Hitler and Mussolini. Of the message of that film, Chaplin said, “I want to see the return of decency and kindness. I’m just a human being who wants to see this country a real democracy.”

While Chaplin’s overall immoral behavior certainly didn’t help his cause, it was his 1938 film Modern Times, which was a satire of industrialization and the machine age, that some pointed to as evidence of his communist sympathies.

But the lack of proof and Chaplin’s adamant professions of innocence were not enough for his adopted country that had been swept up by the Red Scare. He may have been in hot water with the congressional inquiries before, but the light began to shine a little to brightly on him when Representative John E. Rankin of Mississippi began to call for his banishment, claiming Chaplin was “detrimental to the moral fabric of America.”

It didn’t help that Hedda Hopper, the influential gossip columnist, was out for blood when it came to Chaplin, and was tight with FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. “Hopper and Hoover collaborated with one another. She gave him evidence that came to her through the gossip grapevine and he gave her information that the FBI wanted to make public. They were united in the goal to destroy Chaplin who they both believed was a dangerously influential Jewish communist,” Karina Longworth says in her podcast You Must Remember This.

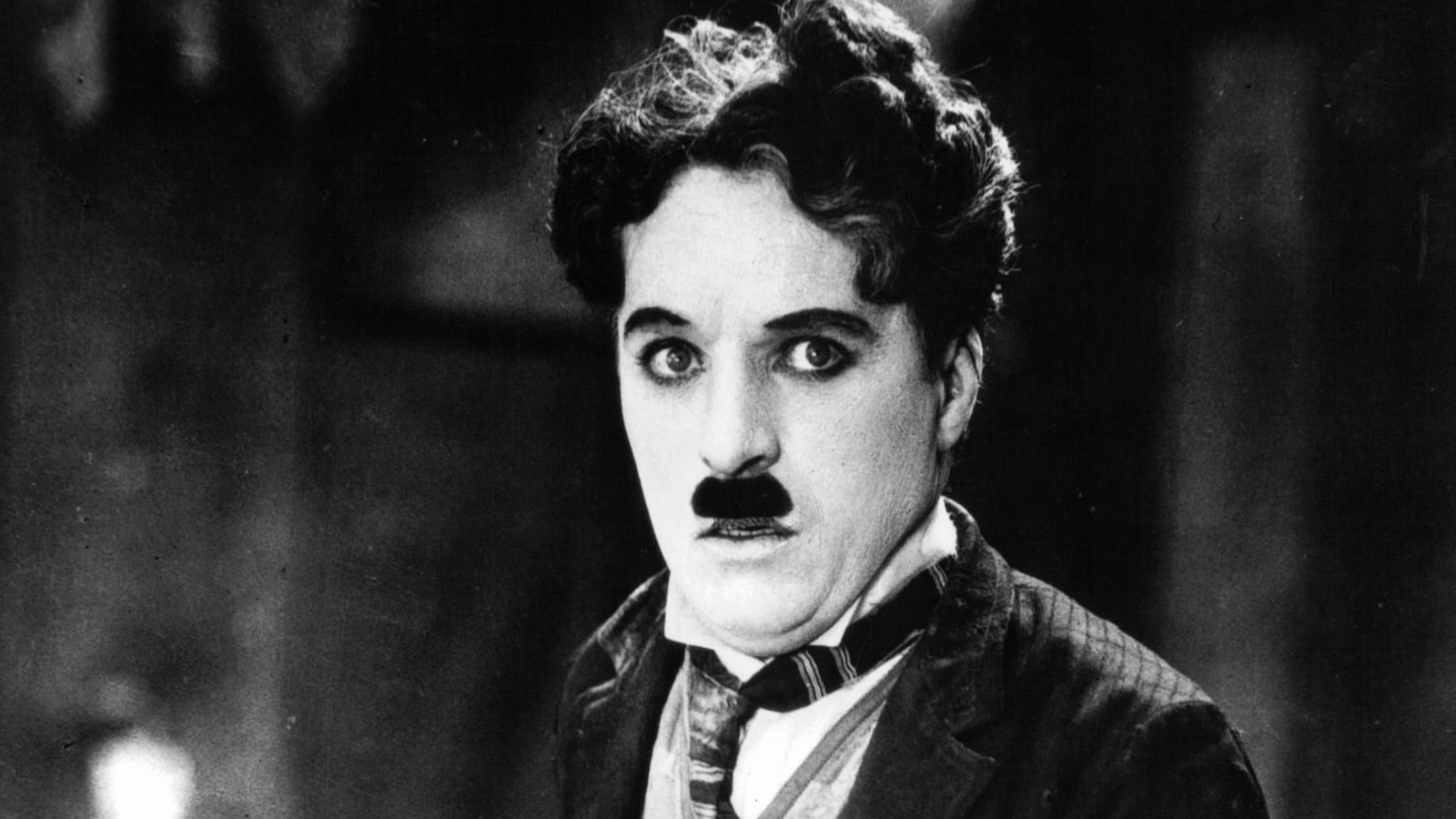

Chaplin, circa 1974.

Horst Tappe/Hulton Archive/GettyAgainst this backdrop, the Chaplin family set sail from New York on Sept. 17, 1952, for what was supposed to be a six-month trip to the homeland he hadn’t visited in over 20 years. Two days after their departure, while the family was warmly ensconced aboard the Queen Elizabeth and Chaplin was enjoying lunch, his publicist who had accompanied him on the voyage received a telegram. The missive informed him that U.S. Attorney General Thomas McGranery had just issued an order banning Chaplin from entering the country and requesting his attendance at an immigration hearing.

Chaplin flat-out refused to cooperate. While this extreme development surely shocked him, a fact attested to by Oona’s mad dash to recover the family money two months later, he had also quietly prepared for something like this, though he never said so outright. Before he left on his trip, he had ensured that Oona, an American citizen, had access to all of his financial accounts.

Despite this startling news, his decision was clear. The U.S. may have been his home for nearly four decades, but he would not cooperate with the witch hunt or risk punishment. If this is how the country was going to treat him, he and his family would make a new home in Switzerland.

Chaplin’s lawyer summed up the betrayal of the incident, explaining, “The immigration was so nice about issuing Chaplin his permit and even told him to hurry back… Now the minute he gets on the high seas this comes up.”

Chaplin, for his part, docked in Southampton five days after being informed about his changed fortunes in the Land of the Free and was greeted by a cheering crowd. Later that day, he again staunchly denied any communist affiliation and said he was a person “who wants nothing more for humanity than a roof over every man's head.”

The British communists, for their part, were happy to greet the star, even if he wanted nothing to do with them. The communist newspaper of London, The Daily Worker, printed a letter welcoming to Chaplin to the city, writing, "His films have lampooned the great and the dictators, raised up the common man against the rich. Now the world’s bully threatens the world’s clown.”

While Chaplin wasn’t officially exiled from the U.S., he was left with no other option than to stay away from the country he called home. This self-exile lasted until 1972, when Chaplin returned to America one last time at the age of 83 to attend the Oscars, where he was receiving an honorary award.

The reception to his grand return was uproarious. After an applause-filled screen of two of his films at the Lincoln Center several days earlier, Chaplin told the crowd, “I feel as if I were the object of a complete renaissance—as if I were being reborn.”

Just over five years later, he died at home in Switzerland, never having stepped foot in America again.