For a time the Middle East seemed like it just froze, the conflicts of yesterday put in quarantine—as so many of us have been—while various countries strive to contain an epidemic of biblical scale. Don’t expect that to last. The coronavirus outbreak is not the great equalizer, nor is it the crisis in which past rivalries will be forgotten.

Like an earthquake, the coronavirus is magnifying the foundational weaknesses of the least prepared countries, exacerbating existing inequalities across the region. And like a particularly lethal aftershock, the crash of the oil price further debilitates petroleum-based economies that lack the financial reserves to weather the secondary blow to their system.

For Gulf countries, the “double whammy” of the coronavirus and the oil shock, while major disruptions, can be weathered with mass injections of capital. Moreover, these countries appear to have been some of the best prepared to deal with the pandemic, likely because they already faced the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreak. They acted relatively quickly and decisively to identify cases and close down their borders. That’s not to say that things aren’t going to be bad for Gulf countries—they will—but there will be different shades of bad.

By contrast, Algeria, Iraq, Egypt, and Lebanon are certain to be hit especially hard by the twin blows. Algeria and Iraq’s budgets are so tied to the price of oil that they have no margin to maneuver. The economic crisis will also hit Egypt, especially with the loss of tourism, while Lebanon was in the process of defaulting on its sovereign debt even before the outbreak really took off.

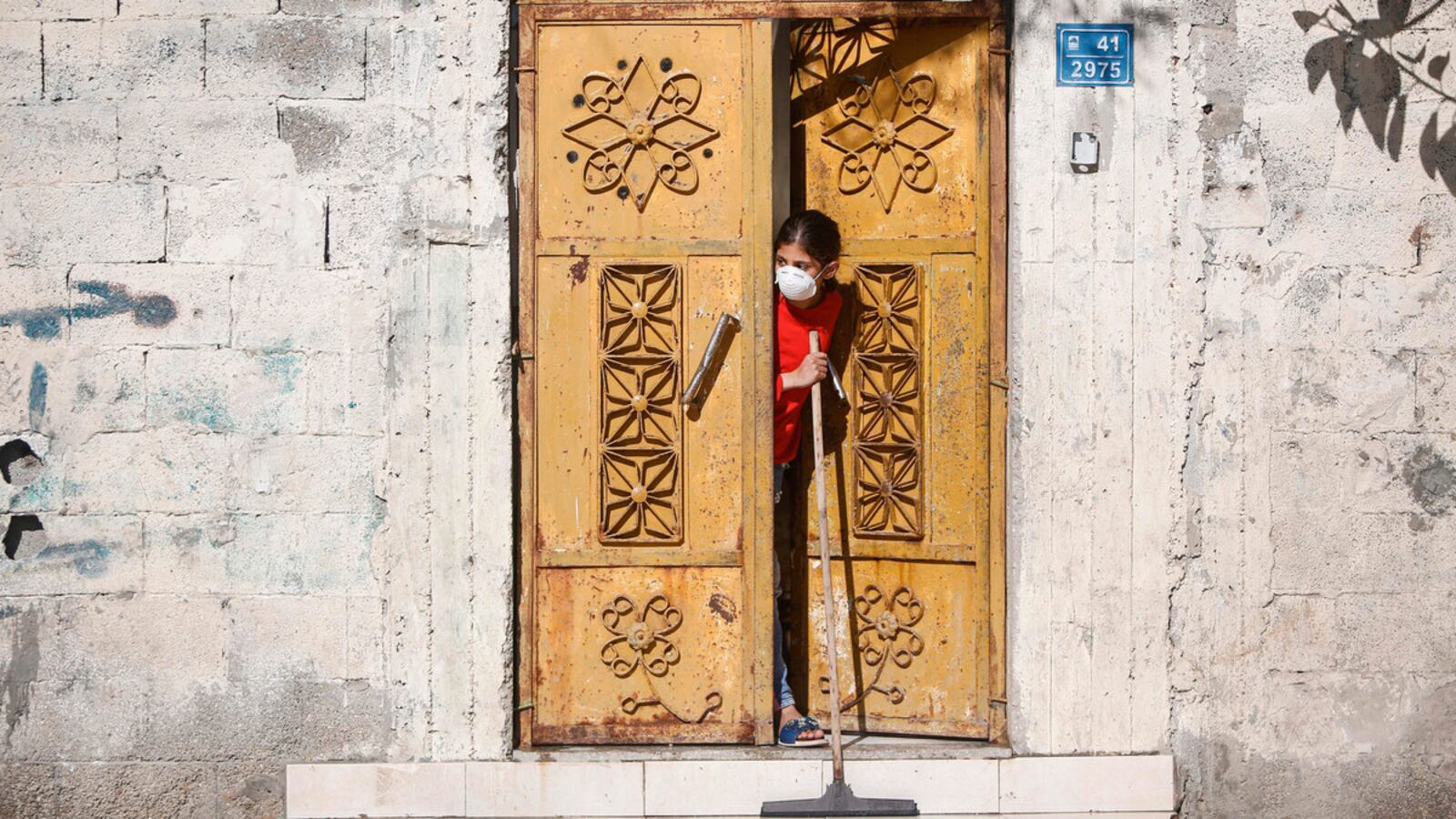

Refugee and internally displaced communities across the region also are going to be hit very hard, which is likely to increase refugee flows both within and outside the region—with potential recipients of these flows having another reason to close their doors. As a result, the burden of these new refugees is poised to be borne most by the states that can least afford to do so and those that already are host to massive displaced populations.

This widening gap will have an impact on the region’s geopolitics. Desperate people do desperate things, and desperate regimes even more so.

The recent escalation in attacks against coalition forces in Iraq which resulted in the killing of two U.S. and UK soldiers in the Taji military base is one example of what could become a trend: namely, the growing need for countries weakened by the outbreak to project strength.

Iran has been at the epicenter of the crisis in the region and its lack of transparency and effort to maintain ties with one of its last trading partners, China, turned the crisis into a nightmare—making us, as geopolitical analysts, wonder what does Iran have to lose and where could its proxies strike next?

Beyond that, as the crisis shifts America’s focus even more inwards, local actors will test Washington’s willingness to respond to escalation. Given what happened in Iran, and the possible geopolitical consequences, this raises the questions of what would (or more likely will) happen if/when the crisis will reach these levels in areas such as Syria, Yemen, Libya or Gaza? In an already unequal world, the crisis may well make asymmetric warfare even more relevant than it already was.

While some regimes struggling against popular protest movements may have perceived a silver lining in the outbreak, a day of reckoning is not far over the horizon.

In Algeria and Lebanon the streets are emptying fast. Now that the scale of the outbreak has set in, most if not all protesters won’t be marching for weeks or months to come. But there will be some reluctance to call off the demonstrations. Some protesters view their local regimes as worse than the virus.

Those who decide to continue demonstrating will face a crackdown rationalized by the outbreak—Algeria already issued a ban on protests. The pandemic will break the momentum of these popular movements, but, once the dust settles, these may also come back swinging at governments that mishandled the crisis. The Middle East and North Africa were in the middle of a second Arab Spring. There’s every reason to expect the uprisings to regain their momentum when “coronavirus season” is over.

On a domestic level, the crisis likely won’t bring people together, at least not in the long term—and not only because of the need for social distancing. Sectarian tensions are liable to increase, particularly as a result of Iran’s catastrophic mishandling of the situation.

In the Gulf, where much of the initial outbreak was the result of Iran-related travels—which are difficult to track given that Gulf citizens who travel to Iran don’t get their passports stamped—fear of a broader outbreak due to such travel is already having an impact, with Saudi Arabia closing the Shiite-majority region of Qatif, and other Gulf countries reluctant to repatriate their own citizens from Iran.

The lack of testing capabilities in Sunni areas of Iraq (when compared to Kurdish and Shiite-majority areas), a similar lack of balance between testing numbers among the Jewish and Arab communities in Israel alongside tensions prompted by lockdown measures in Jaffa, all highlight the possibility that the outbreak will widen domestic divides rather than bridge them.

In Israel, the crisis has revealed—overnight—the government’s willingness to approve massive spying on its own population at a time when parliament can’t convene to monitor the use of data gathered by the Israeli Security Agency.

This is not an isolated case: more broadly, containment measures and the subsequent reaction by their respective populations will widen the gap between governments who managed to gain public trust, and those who didn’t.

All of these factors suggest the coronavirus pandemic will turn into a defining moment for the region, not simply because of its magnitude, but because it came at a time when most countries were experiencing their own political crises—and failed to build any immunity to the one that suddenly knocked at their doors.