The second decade of the 21st century has been a sobering one for many Americans, especially those who have interpreted racial progress as an indication of the end of racism. For those well-versed in both the distant and recent past, claims of a post-racial era smack not only of naivety but ignorance. As even a cursory glance at any online comment section is likely to reveal, racism is widespread, and its proponents still walk among us.

Americans have long underestimated the nation’s race problem, assuming the transition from a nation that for hundreds of years sanctioned slavery and white supremacy to one that embraces full racial equality would be an easy one. In fact, the transition will continue to be difficult, requiring much more than the time that’s passed since the landmark legislation of the mid-20th century. Nevertheless, we should not despair.

For history shows that as long as there has been racism there has been resistance to the idea. Though only recently attracting scholarly attention, interracialism⎯defined briefly as companionship, collaboration, and cooperation across racial lines⎯is as much a part of American history as is racial division and strife. Even when and where you would least expect to find interracial friendships and alliances, they have always existed.

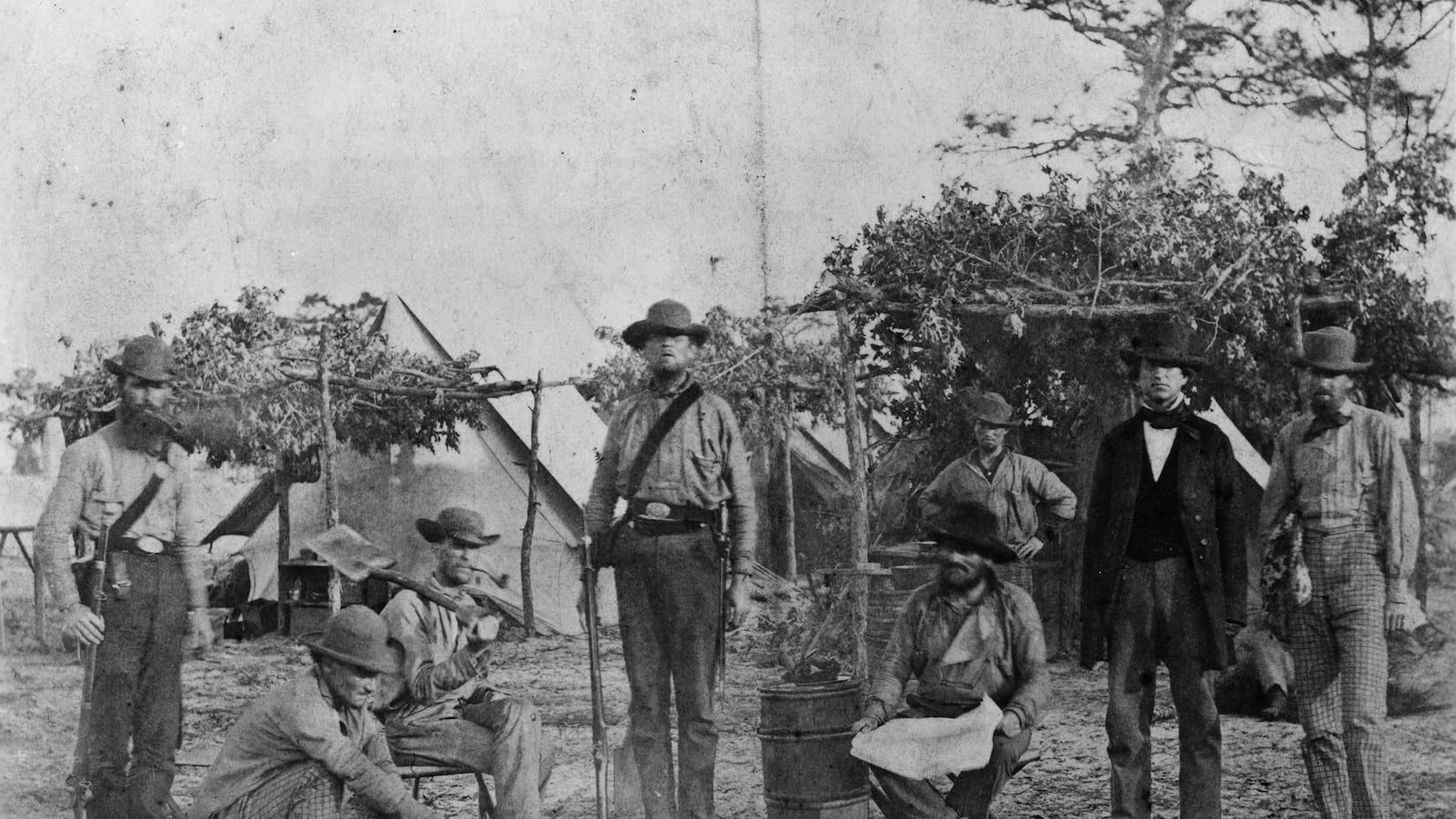

Take Pensacola, Florida, during the Civil War. In terms of politics, culture, and geography, it’s a city more Deep South than South Florida, resembling Mobile and Montgomery as opposed to Miami. Given this, you might not expect to discover the widespread resistance to slavery and white supremacy in the far-west Florida Panhandle during the heyday of secessionism and the rise of the Confederate States of America. But there was.

Though little-known today, the Civil War almost started in Pensacola when newly elected President Abraham Lincoln ordered men and supplies to reinforce Fort Pickens, a massive hexagonal brick citadel on the opposite side of Pensacola Bay. Lincoln wanted to provoke Confederates into firing the first shots of the war at Fort Pickens—because of its defensibility. That plan failed when Army leaders ignored the commander in chief’s orders and handed Pensacola and the adjacent navy yard to the Confederacy without a fight.

Despite the setback, Union forces managed to hold Fort Pickens for the duration of the war. As the largest federally controlled fortification in the Deep South, it became a beacon of freedom, attracting hundreds of fugitive slaves. It was, in the words of one soldier stationed there, “the point to which the Negroes fled after the outbreak of the war, from all surrounding districts, as it was for some time the only point in the extreme South which was held by federal troops, and where they could be safe.”

A look at two separate incidents involving fugitive slaves, who tried to reach Fort Pickens and instead ended up facing a Confederate court-martial, proves the existence of interracialism at a time and place considered entirely hostile to the practice. The first involved five enslaved laborers claimed by Jackson Morton, a Florida state senator and one of the most powerful men in region. The men, Peter, William, Robert, George, and Stephen, claimed they were well-treated by Morton, but when he threatened to move them to Alabama, they stole several boats docked near Morton’s plantation and began the dangerous journey down the Blackwater River toward Fort Pickens.

When they were arrested by Confederate sentinels several days later, the slaves took full responsibility for the escape attempt, openly avowing their desire to be free; nevertheless, they admitted that several white men helped convince them to abscond. According to Confederate court records, the Southern race traitors included Mayo, a well-known grog-shop owner in a small industrial village north of Pensacola; Chance, a contractor who worked for Morton near Mayo’s shop; and Garrett, a lumber trader who plied the nearby waters. For more than a year, each of these free white Southerners risked their lives and livelihoods by encouraging their enslaved black associates to run away, proclaiming that because of Lincoln’s election they were as free as white men “and that they were fools if they did not go to Pickens as it was easily done.”

In the second incident, a bondsman from Pensacola named Ebenezer made his way to Fort Pickens carrying newspapers and other materials considered “useful to the United States troops stationed there and injurious to the Southern Confederacy.” After being apprehended and taken aboard a Confederate steamship, the “intelligent being” likewise admitted to having several white accomplices. Lockly, a mysterious man with a reputation for befriending his black neighbors, provided the boat on which Ebenezer tried to escape and even sailed with him part of the way to Fort Pickens before being “knocked overboard by the boom.” Melmore was also notorious in Pensacola as he was “the habitual associate of Negroes⎯and places himself upon equality with them.” When Ebenezer began plotting his escape to Fort Pickens, he asked the “Irishman” if there was truth to Ebenezer’s owner’s claim that the “Yankees” at Fort Pickens treated fugitive slaves severely. Melmore told Ebenezer that everything his owner told him “was a damned lie—that if he went over to the Yankees he would be so well treated that they would give him work and pay for it and Send him to New York or Liberia.”

In the end, the Confederate court-martial found each of the runaways guilty on all charges. But before officials could carry out the punishments, which ranged from hundreds of lashes to death by hanging, Confederate troops evacuated Pensacola, returning the city and surrounding areas to the Union. With the exception of Garrett, whom the court acquitted of unknown charges, the fate of “the traitorous people with white skins” who encouraged and assisted these and countless other runaways to Fort Pickens is unknown. Still, before leaving Pensacola, a high-ranking Confederate commander warned “those Monsters and vile wretches in the shape of white men” of the dangers they faced should they ever betray their race again.

Further evidence of interracialism surviving in the Antebellum and Confederate South comes from the last two years of the war, when Union-occupied Pensacola served as a base for thousands of black and white soldiers and refugees. Among them were James Summerford and Wade Richardson, two young white abolitionists who traveled from central Alabama to enlist in the Union Army. According to a memoir written years after the war, Summerford came from a family of “strong abolitionists,” while Richardson was the son of a Universalist preacher who “extended his creed to include all men, black and white, good and bad, in his scheme of universal redemption.” Richardson’s uncle, also an abolitionist, nearly lost his life to an angry mob near Tuskegee, Alabama, following Lincoln’s election, when he refused to enlist in a Confederate regiment because of his opposition to slavery and secession.

Summerford and Richardson nearly failed to reach Pensacola as the entire region was controlled by Confederates, yet they managed to avoid detection with the assistance of black slaves, who readily volunteered information on the movement of Confederate troops, along “with a bit of bread or a roasted potato or ear of corn.” When the two finally reached their destination, both fell victim to yellow fever. Summerford succumbed to the disease within days, but Richardson managed to survive thanks to the selflessness of a “colored nurse.” “The woman’s treatment was heroic, I assure you,” Richardson recalled, “but thanks to her, I survived.” After recovering, Richardson enlisted in the First Florida Cavalry, a Union regiment consisting almost entirely of white Southerners who spent much of the remainder of the war freeing hundreds of slaves along the Gulf Coast.

Civil War Pensacola reminds us that history is an important teacher. While large numbers of American citizens have found white supremacy an attractive ideology worth fighting and even killing for, it is just as important to remember that the dream of racial equality has also always attracted a wide following—even when and where believing such an idea came at great cost. As we continue to move forward amid the jarring sounds and arresting images of racial discord, it would be wise to remember our past and have faith in our future, anticipating the day when our nation will again be touched, as Lincoln promised, “by the better angels of our nature.”

Matthew Clavin is the author of the new book Aiming for Pensacola: Fugitive Slaves on the Atlantic and Southern Frontiers published by Harvard University Press.