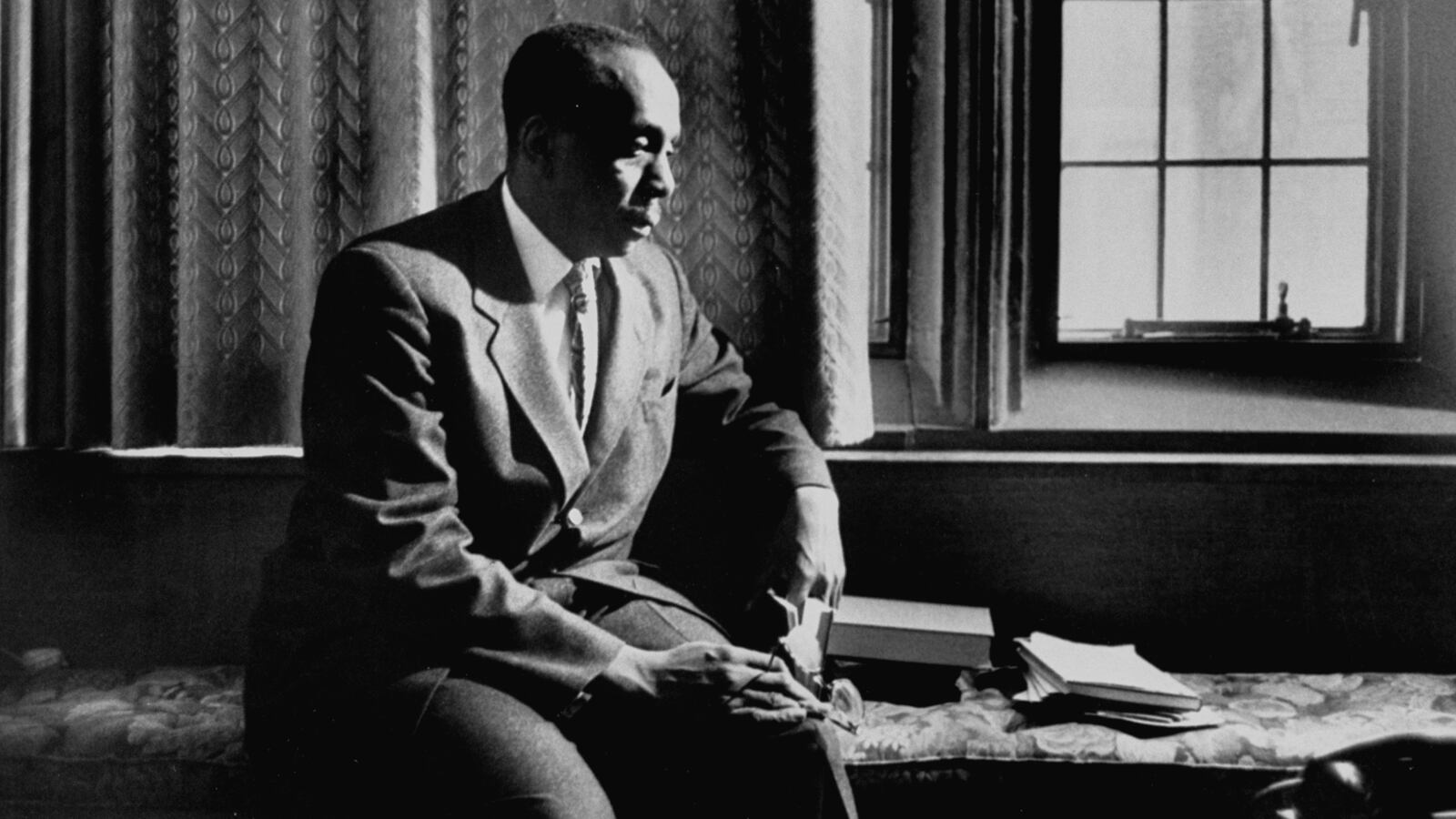

Howard Thurman was born in Florida in November 1899, and was raised in Daytona, primarily by his mother and grandmother. By dint of his native intelligence, determination, and ability to circumvent a system that was established to thwart Black Floridians, he received a first-rate education at Morehouse College and Rochester Theological Seminary and thereafter became an influential minister, much in demand before both Black and white audiences.

He was one of the first prominent Black advocates of radical nonviolence, and in 1936 met with Mahatma Gandhi in India. He had teaching positions at Morehouse and Spellman colleges and Howard University. In 1944 Thurman left his comfortable position at Howard to become pastor at the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples in San Francisco, one of the first churches in the United States organized on an interracial and interdenominational basis. In 1953 he became dean of chapel and professor of Spiritual Disciplines and Resources at the Boston University School of Theology.

Although he was never a front-line activist—he preferred to offer advice and spiritual counsel from behind the scenes—he inspired many future leaders of the civil rights movement, among them James Farmer, Pauli Murray, and Martin Luther King, Jr. A mystic, he was an influential proponent of the spirituality of personal exploration, and helped shape a new liberal American religiosity, increasingly untethered from the traditional Christianity of creeds and denominations.

He retired from Boston University in 1965, and spent his remaining years, actively writing and teaching, until shortly before his death. He was the author of more than 20 books, among them Jesus and the Disinherited (1949), one of Martin Luther King Jr.’s favorite books, and The Search for Common Ground (1971).

On Feb. 21, 1936, Howard Thurman, his wife, Sue Bailey Thurman, and Edward Carroll arose around midnight from their hostel in Bombay. They comprised three-fourths of the Negro Delegation sent by the American Student Christian Federation on a “Pilgrimage of Friendship” to their Indian counterparts. (The fourth member of the delegation, Edward Carroll’s wife, Phenola Carroll, was indisposed.)

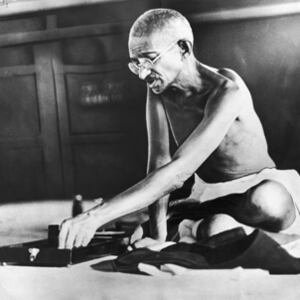

By Feb. 21, the delegation had been on an extended speaking tour of British colonies in South Asia for four months. This night was special. After getting ready, Howard, Sue, and Edward Carroll boarded a train. About four hours later, they arrived at Navsari Station, about two hundred miles north of the city. They were met by Mahadev Desai, Mahatma (Mohandas) Gandhi’s longtime personal secretary. While Sue and Edward Carroll rested in a bungalow, Howard chatted with Desai. At dawn they all got into Desai’s battered Model T Ford for the 20-mile drive over a badly rutted dusty road to Dharampur in the native state of Bardoli, where the Indian Congress Party had a compound. (In the political patchwork that was British India, Bardoli was one of the more than 550 princely or native states, areas that enjoyed a slightly greater measure of self-governance than areas directly under British control.) The three would shortly become the first African Americans to formally meet with Gandhi, the world-famous leader of the Indian independence movement.

Gandhi bounded out of his tent bungalow to meet the visitors. Desai told Thurman he had never seen Gandhi greet visitors so effusively or enthusiastically. The first thing Gandhi did was to pull out a pocket watch from under his dhoti and say, “I apologize, but we must talk by the watch, because we have so much to talk about and you have only three hours before you have to leave to catch your train back to Bombay.” Mahadev Desai kept notes from the meeting with Gandhi and the Negro Delegation and would publish an account of the meeting the following month in Gandhi’s magazine Harijan, under the title “With Our Negro Guests.”

Gandhi started to pepper the delegates with questions. “Never in my life,” Thurman would later write, “have I been a part of that kind of examination: persistent, pragmatic questions about American Negroes, about the course of slavery, and how we survived it.” Gandhi asked questions about voting rights, lynching, discrimination, public school education, and Black churches. Thurman provided a short history of African Americans since Emancipation, explaining to Gandhi “the various schools of Negro thought,” in Desai’s words, “with the cautious and dispassionate detachment characteristic of a professor of philosophy.”

Thurman began with Booker T. Washington. Throughout his time in India, Thurman emphasized Black accomplishment and what had been achieved in the 70 years since Emancipation, an anniversary he often mentioned in his talks. He was always complimentary to Washington, emphasizing less his racial compromises than what he had achieved and built despite the formidable barriers he faced. The previous November, in Palamcottah, a newspaper account of Thurman’s talk, “The Faith of the American Negro,” reported that Thurman spoke of how Washington and his peers tried to uproot “the slave mentality of the race. They soon brought into existence a new way of knowledge and thinking and understanding. They developed in the minds of the Negroes a deep faith in their own strength and abilities.”

If Thurman admired Washington, he also thought that his era had passed. He told Gandhi that Washington’s ideas no longer made sense in an era of urbanization, mass production, and industrial unionism. Citing W. E. B. Du Bois’ recently published Black Reconstruction, Thurman provided a history of the South that emphasized the role of white working-class resentment in shaping racial attitudes.

Thurman told Gandhi of the “theory of the separate but so-called ‘equal’ education of the Negro.” He had told an audience some two months earlier that the goal of Black education since Emancipation was not to build Black institutions for their own sake but to give Blacks “a certain social attitude that can be injected into American society, so that it will become increasingly impossible to have separate schools for whites. The Negro attack is directed against segregated institutions of the present day.” In other words, the justification for segregated educational institutions was educating their students to question the existence of segregated institutions.

When Gandhi asked, “Is the prejudice against color growing or dying out?” Thurman’s answer was ambivalent: “It is difficult to say.” He seemed most optimistic, somewhat surprisingly, about the situation in the South, where, probably reflecting his interaction with southern white students, Thurman found a “disposition to improve upon the attitude of their forebears.” However, he added that the “economic question is acute everywhere,” and that “in many of the industrial centers in [the] Middle West the prejudice against Negroes shows itself in its ugliest form,” and he worried about clashes between white and Black workers. When Gandhi asked, “Is the union between Negroes and the Whites recognized by law?,” Edward Carroll told him that such marriages were illegal in a majority of the states and that as a Black minister in Virginia he had to post a $500 bond and forfeit it if he ever solemnized an interracial marriage. Thurman, a strong feminist, added that these laws especially hurt Black women: “But there has been a lot of intermixture of races as for 300 years or more, the Negro woman had no control over her own body.” A possible subtext to this part of the conversation was Gandhi trying to make amends for a controversial 1930 book in which he seemed to oppose interracial marriage. This provoked outrage among some of Gandhi’s African American supporters, leading to his statement in the Baltimore Afro-American in 1934 that “prohibition of marriage between colored people and white people I hold to be a negation of civilization.” . . . .

At this point, it was the visitors’ turn to ask Gandhi questions. Sue, whom Desai credited as being “nobly sensitive to the deeper things of the spirit,” posed some of the knottier ones: “Did the South African Negro take any part in your movement? [during the two decades, from 1893 to 1914, that Gandhi lived in South Africa].” “No,” answered Gandhi, “I purposely did not invite them. It would have endangered their cause. They would not have understood the technique of our struggle nor could they have seen the purpose or utility of non-violence.” This was a questionable defense of a dubious strategy. Gandhi’s comments to the Negro Delegation indicate that he was still not free of stereotypes of Africans as unusually violence-prone. As for practical results, the policy of excluding Africans from Gandhi’s campaigns might have resulted in some short-term term tactical victories, but it is difficult not to conclude that this decision significantly contributed to the ultimate failure of his South African satyagraha campaign.

The conversation then turned to, in Desai’s words, “a discussion which was the main thing that had drawn the distinguished members to Gandhiji,” the philosophy of nonviolence. Although “nonviolence” is a term that Gandhi coined—his is the earliest citation in the Oxford English Dictionary, from 1920—he never liked the term, as he told the delegation, because, of “the negative particle ‘non.’” “It is no negative force,” he said, but is rather “the greatest and the activest force in nature,” a translation of the Jainist concept of ahimsa, respect for all living things, Gandhi’s Sanskrit term for the concept. (“Satyagraha” is giving ahimsa a concrete political task to accomplish.) “Superficially,” he told Thurman and the others, we are “surrounded by life and bloodshed, life living upon life,” but ahimsa is the deeper and truer reality, “a force which is more positive than electricity and more powerful than [the] ether.” When Thurman asked if nonviolence “overrides all other forces,” Gandhi replied, “Yes, it is the only true force in life.” Nonviolence, or ahimsa, for Gandhi was less an idea than a physical and moral reality. It was the Force.

This force could be channeled by its masters. Worldly goods and material possessions limit its effectiveness. “It possesses nothing, therefore it possesses everything.” And though it was open to everyone and anyone—“if there was any exclusiveness about it, I should reject it at once”—very few had mastered it. Gandhi, who could toggle easily between abject humility and extraordinary hubris, suggested to Thurman that if just one person had grasped and learned the meaning of ahimsa, it might be possible for just “one single Indian to resist the exploitation of 300 million Indians.” He hoped to accumulate sufficient “soul-force” to do this, but he acknowledged to Thurman that he was still far, very far, from this goal…

Sue, no doubt slightly wearying of this airy metaphysical discussion, tried to bring the conversation around to some of the practical consequences of ahimsa and satyagraha: “How am I to act, supposing my own brother was lynched before my eyes?” There is, Gandhi replied, “such a thing as self-immolation.” Self-immolation was a difficult doctrine indeed, as difficult as it sounded. It was a recognition that nonviolence rested on personal suffering and absorbing sufficient suffering to change the behavior of others: “I must not wish ill to these, but neither must I co-operate with them.” If your livelihood is in any way dependent on the community of lynchers, one must find alternative means of support, refusing “even to touch food that comes from them, and I refuse to co-operate with even my brother Negroes who tolerate the wrong.” The only life you can take to address evil and injustice is your own: “One’s faith must remain undimmed whilst life ebbs out minute by minute.” Perhaps sensing that the delegates were not entirely persuaded, Gandhi added that he was “a very poor specimen of the practice of non-violence, and my answer may not convince you.” But this was his faith. He had given the delegates much to consider. The conversation began to draw to a close. The delegates begged Gandhi to come to America. Sue was even more specific: “We want you not for White America, but for the Negroes, we have many a problem that cries out for solution, and we need you badly.” Gandhi said it was impossible. “How I wish I could,” but he had to “make good the message here before I bring it to you.” In any event, he implied, what Black Americans needed wasn’t Gandhi in the flesh but their own Gandhian movement, authentic to their own needs and ideals…

There are two different accounts of the end of the meeting. In his autobiography, Thurman writes that at parting, he asked, “what is the greatest handicap to Jesus Christ in India?” Gandhi told him that it was “Christianity as it as practiced, as it has been identified with Western civilization and colonialism.” The greatest enemy of the message of Jesus in India is “Christianity itself.” This was a sentiment Thurman had heard many times while in India, and it was one with which he heartily agreed.

But the Desai account, “With Our Negro Guests,” published in 1936, became the main reference for the interview. In Desai’s retelling, Thurman told Gandhi that “the Negroes were ready to accept the message” of nonviolence, and Gandhi replied, in his closing comment as he said good-bye, “Well, . . . if it comes true it may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of non-violence will be delivered to the world.” The civil rights movement, of course, has no single starting date, and the question of when it began has been vigorously if inconclusively debated. But if one had to pick a day, Feb. 21, 1936, the date of Gandhi’s benediction to the budding Negro revolution, is as good as any.

After Thurman returned from India in April 1936, one of the first places he visited was Atlanta. While there, he had dinner with his old friends Martin Luther King Sr. and Alberta Williams King. With seven-year-old Martin Luther King Jr., presumably in earshot, he talked of his adventures in India and his meeting with Gandhi. Thurman told this story to the historian Vincent Harding, and both men thought there was some deeper significance to this meeting, something stronger than coincidence. If indeed, as Gandhi told Thurman, “it may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of non-violence will be delivered to the world,” Thurman wasted no time in passing on the message to the person who would be most responsible for fulfilling it. (If nothing else, the story demonstrates that the younger King knew Thurman from his earliest days.)

Two decades before King burst into political prominence, Thurman was one of the prime deliverers of the message of African American nonviolence. There were many who were listening. In August 1942 Thurman was interviewed by a reporter from the Pittsburgh Courier. Thurman was in a feisty mood. He was angry that Churchill had recently rearrested Gandhi and the leaders of the Congress Party in India. “The imperialist stubbornness of Britain” had reduced their claims to be fighting for democracy “to a moral absurdity.” Try as they might, in their usual brutal fashion, the British will not be able to lock up the “spirit of present day India” however many jails they build. The reporter took the measure of the “modest, stocky black man, with resonant voice and smiling countenance” before him. He had, he told his readers, “probably moved more cynical men and intellectual women than any other speaker of his generation.” This man was a mystic, “but a mystic with a practical turn of mind” who understood politics and economics. The reporter, Peter Dana, suggested that Thurman was “one of the few black men in this country around whom a great, conscious movement of Negroes could be built, not unlike the great Indian movement with which Gandhi and Nehru are associated.”

History took another path, and neither Thurman’s talents nor temperament were suited for the role of lead strategist and tactician for a national political movement. But in the years after his return from India, in the late 1930s and early 1940s, when his advocacy for nonviolence was at its freshest and most ardent, he was being heard. After his return to the United States Thurman would spend several years crossing the continent from Canada’s Maritime provinces to California trying to explain, to himself and his audience, “What We May Learn from India,” to borrow a frequent lecture title. He was a prime shaper of a distinctive, radical African American interpretation of Gandhian nonviolence, placed into a broadly Christian framework, one that Martin Luther King Jr., when he was old enough, and many others, would inherit.

Reprinted from Against the Hounds of Hell: A Life of Howard Thurman by Dr. Peter Eisenstadt, by permission of the University of Virginia Press (copyright 2021).