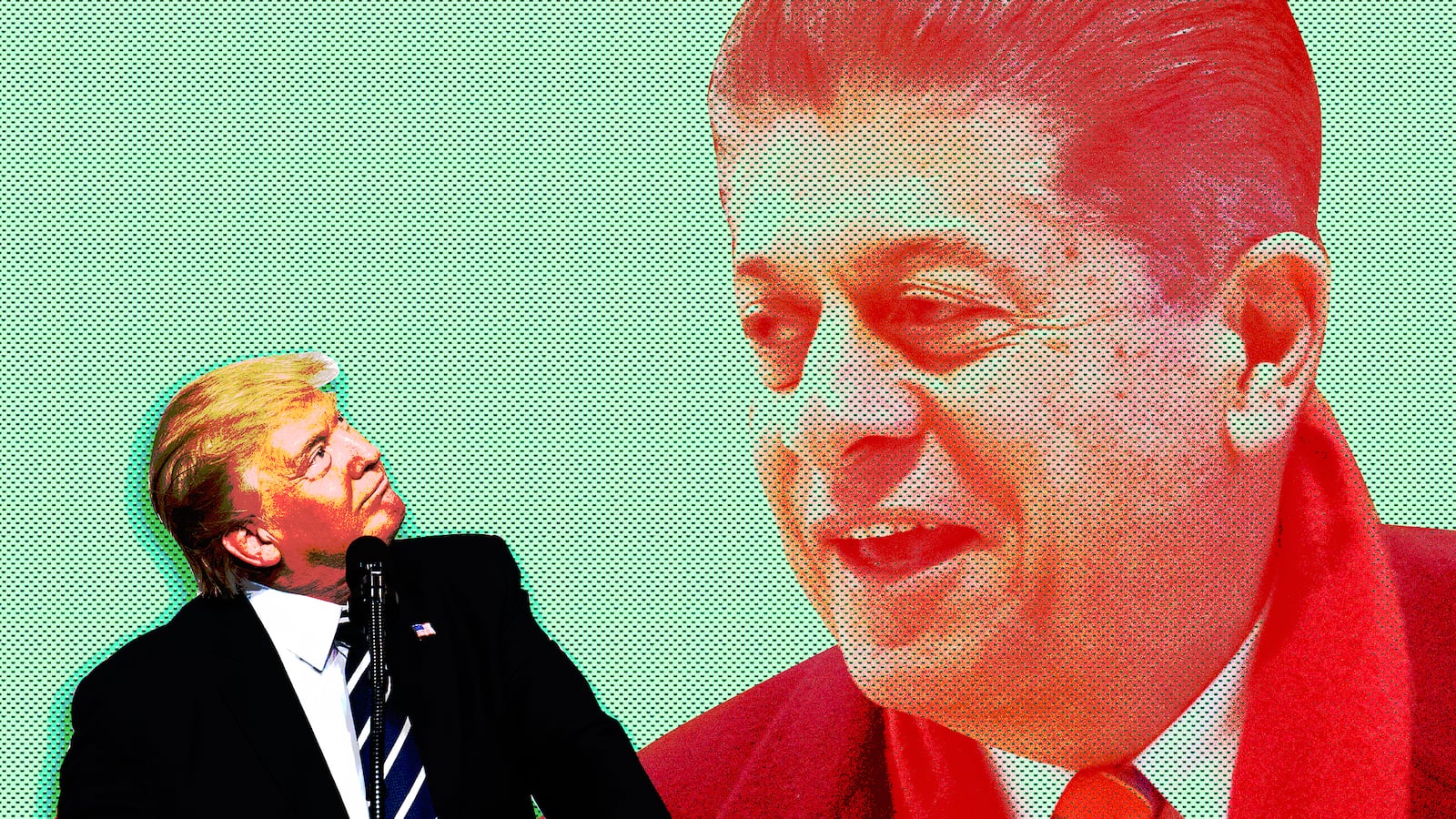

Fox News personality Andrew Napolitano—best known to viewers of the Donald Trump-friendly cable outlet as “The Judge,” in deference to his long-ago stretch on the Superior Court bench in New Jersey—is emerging as one of the 45th president’s more influential, if unconventional, ex-officio advisers.

The latest example of the judge’s curious sway with Trump occurred earlier this month, when Napolitano’s Jan. 11 appearance on the president’s favorite television show, Fox & Friends, prompted Trump to post a tweet parroting the judge’s vehement opposition to legislation renewing FISA—the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act—and expanding government powers to conduct warrantless mass surveillance of U.S. citizens, and to use the takings for criminal investigations unrelated to terrorism.

The presidential tweet, which contradicted official White House policy, sowed panic, confusion, and anger among congressional Republicans who were voting on the issue that day in the House. It was only after White House staffers and House Speaker Paul Ryan staged an intervention that Trump reversed himself and suddenly realized that he actually supported the legislation.

The 67-year-old Napolitano—who declined to comment for this story—is a libertarian absolutist who, like Trump, has indulged a weakness for conspiracy theories and entered into a mutual admiration society with Infowars charlatan Alex Jones, who has praised the judge as “an amazing judicial legal mind” and “a patriot who loves America and stands for our constitutional republic.”

Unlike many libertarians, Napolitano, a self-described “pre-Vatican II traditionalist Catholic” who regularly attends Latin mass, is a fierce opponent of abortion rights, a position he frames as consistent with the libertarian “non-aggression” principle against taking life without moral justification. “There is no moral justification for killing a child in the womb,” he argues.

The judge, a graduate of Princeton University and Notre Dame Law School, is also a legal and constitutional scholar who has written nine popular books with dystopian titles such as Lies the Government Told You, A Nation of Sheep, and Theodore and Woodrow: How Two American Presidents Destroyed Constitutional Freedom.

Indeed, Napolitano’s beliefs frequently clash with Republican and Democratic orthodoxy and even the policies of the Trump administration.

He has argued that all narcotics should be legalized along with prostitution; that the government has zero authority to regulate consensual sexual behavior or, for that matter, prohibit same-sex marriage; that police officers regularly lie under oath in order to secure wrongful convictions; that government regulations of food, business, and the environment should be rescinded as unwarranted intrusions on the free market; that the United States should not be projecting military power to lead the Western international order; that the Justice Department has regularly shredded the Constitution in order to persecute Muslims; that the government’s official version of the 9/11 attacks, especially what caused the collapse of World Trade Center 7, could well be a sinister fabrication; and that George W. Bush and Dick Cheney “absolutely should have been indicted for torturing, for spying, for arresting without warrant.”

After he made the latter assertion—in a 2010 C-SPAN interview with perennial presidential candidate and consumer advocate Ralph Nader—then-Fox News Chairman Roger Ailes summoned him to his office and “took him to the woodshed,” according to an informed source.

Napolitano had forgotten he’d done the interview—which aired several weeks after the taping—and the angry Ailes was displeased that he’d learned about it from an indignant member of the Bush family. (Napolitano has privately professed ignorance of the sexual misconduct accusations against Ailes, who died last May.)

More eccentrically, the judge remains a harsh critic of the country’s most sainted president, Abraham Lincoln—“Dishonest Abe,” as he calls The Great Emancipator—who “misled the nation into an unnecessary war,” and was less interested in freeing the slaves (which, in Napolitano’s questionable view, would inevitably have happened anyway) than in becoming a bloody dictator who jailed thousands of political opponents, quashed the First Amendment, and presided over the needless deaths of hundreds of thousands of citizens.

“In Judge Napolitano’s defense,” said longtime admirer (and Daily Beast contributor) Nick Gillespie, editor of the libertarian-leaning Reason magazine, “he really hates all the other presidents as well.”

Apparently Donald Trump is an exception. By most accounts, Napolitano has met and spoken with Trump multiple times since the election—“numerous engagements with him on the telephone and in person,” as he boasted this week on Fox News’ Outnumbered—and he frequently mentions that he has a “business connection” with the president, in that he owns an apartment in the Trump International Hotel and Tower on Manhattan’s Columbus Circle.

The judge has privately told friends, albeit with appropriate skepticism, that Trump has mused about the possibility of nominating him to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Napolitano, who met with Trump during the post-election transition to advise on constitutional issues and Supreme Court prospects, wasn’t enthusiastic about Trump’s candidacy in 2016 (“the lesser of two evils,” and only a slight improvement on Hillary Clinton, he said). “I don't think there's a libertarian bone in Mrs. Clinton's body,” he told Gillespie in a Reason TV interview, “and I don’t know of one in Donald Trump’s body.”

While the judge occasionally criticizes the president’s positions on the air, he does so diplomatically. In private, however, he is said to be scathing about Trump’s lack of policy knowledge, undisciplined brain, scattershot speaking style, and apparent aversion to reading.

Still, the portly, 5-foot-7 Napolitano claims to be amused by the (allegedly) 6-foot-3 Trump’s continual mockery of his height—what passes for the president’s sense of humor.

Unlike Trump—who has assumed the role of president-as-insult-comic, and seems to revel in his mushrooming list of enemies—the judge is fanatically congenial, greets both men and women with hugs and kisses, and tends to address even folks he’s never met before as “My dear friend!”

Napolitano’s actual friendships cut across party and ideological lines—ranging from Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul and his libertarian father, former Texas congressman Ron Paul, to right-leaning Republican Sen. Mike Lee of Utah, to former New Jersey Sen. Robert Torricelli, a liberal Democrat who regularly joins the judge for raucous dinners at Italian restaurants with a diverse group of pals.

In the acknowledgements section of his 2014 book Suicide Pact, about how expanding presidential power has eroded civil liberties—with a forward by Sen. Paul—Napolitano writes that New Jersey attorney James C. Sheil, who died at age 48 in March 2013, was his best friend, literary collaborator, and “alter ego.” He wrote: “Jim and I shared much of our lives with each other... Yet our philosophies and politics were like oil and water.” Napolitano wrote that he dedicated the book to Sheil’s memory.

“His life cut short devastated me,” Napolitano wrote, “but gave me an editor and advocate in Heaven. May the angels deliver him into Paradise, if they haven’t done so already.”

At Fox News and the Fox Business Network—where he hosted his own show, Freedom Watch, for several years until it was abruptly canceled in 2012 (a setback that still rankles him)—Napolitano is famous for carting bushels of apples, corn, and pears into the green room for colleagues from his farm in northern New Jersey, where the maple syrup season is about to commence.

The eldest of three sons of second-generation Italian-Americans—his parents, retired employees of the New Jersey Bell telephone company, are still around at age 92—Napolitano was born in Newark and grew up in the suburb of Bloomfield.

Through his local congressman, Democrat Rep. Peter Rodino—who later became chairman of the House Judiciary Committee that launched impeachment proceedings against Richard Nixon—young Andrew served as a House page in Washington, and attended the page school before ultimately landing at Princeton.

In his 2006 book, Constitutional Chaos, he wrote that as an undergraduate, he held views that he would find repugnant today. “I was a strong and vocal conservative,” he wrote. “I even once wore a T-shirt in 1970 that proclaimed ‘Bomb Hanoi’! I thought Richard Nixon’s law-and-order, pro-police platforms in 1968 and 1972 were right for the country.”

His libertarian epiphany came two decades later, after moderate Republican New Jersey Gov. Tom Kean appointed him to a judgeship on the Superior Court, where he became increasingly alarmed at police violations of the Fourth Amendment prohibiting unjustified searches and seizures, and at the cops’ flagrant and repeated perjuries in court.

“As a judge, I heard the police lie and lie again,” wrote Napolitano, who during his eight years on the bench presided over more than 150 civil and criminal jury trials involving, rapes, murders, robberies, and medical malpractice among other cases. “I remember one case in which a driver had been pulled over and directed to walk away from the car by one cop, while his partner secretly kicked in the car’s tail light. Why? To give the police a legal reason for the pull-over should it come up in court.”

He concluded: “The one incontrovertible lesson I learned over those hard, disillusioning years: Unless you work for it, sell to it, or receive financial assistance from it, the government is not your friend.”

Napolitano is widely considered a thought leader in the libertarian movement. Gillespie, for one, said: “He’s definitely in the pantheon of contemporary libertarian commentators and public intellectuals.”

“He doesn’t just walk on water, he runs on water,” said prominent libertarian theorist Walter Block, a professor of economics at New Orleans’ Loyola University.

Rand Paul, meanwhile, called Napolitano a “hero” in a statement to The Daily Beast: “In a world where economic liberty somehow became separated from personal liberty, the Judge has a unique ability to bring all liberty back together with logic, laughter, and warmth,” the senator wrote.

Ralph Nader, who occasionally speaks with the judge, said: “He’s basically an academic sage operating in a frenetic circus… To analyze him, you’ve got to divide him. There are different Napolitanos. There’s the Napolitano that reacts to his intellect and his sense of justice—that’s reflected in his books. And then there’s the Napolitano that reacts to Fox’s investment in him—and that’s his two-minute or one-minute spiels for the masses.”

Which arguably includes Trump.

Last March, the judge’s on-air commentary famously provoked an international incident when the president and White House press secretary Sean Spicer approvingly cited Napolitano’s claim that British intelligence operatives had surveilled Trump Tower during the 2016 campaign as a favor to Barack Obama—a “Bad (or sick) guy!” for ordering the supposed “wiretap,” as Trump had tweeted days earlier without evidence.

After British government officials furiously denied the accusation and objected to the White House’s legitimization of it, the president defiantly called Napolitano a “very talented legal mind.”

Fox News was compelled to retract the judge’s damaging assertion, and Napolitano was suspended from the airwaves for a couple of weeks; a controversy over fake news with the British authorities was not calculated to help Fox News parent company 21st Century Fox’s case with U.K. regulators that it be permitted to acquire 100 percent of Sky Television (a $16 billion bid that was disallowed last week).

Napolitano, however, continues to maintain that he was correct in the first place.

Not that Napolitano’s opinion has always had the desired impact. This week, for instance, the president expressed his willingness to be interrogated “under oath” by special counsel Robert Mueller even as the judge spent day after day going on Fox News and the Fox Business Network to repeatedly urge the opposite.

“You don’t talk to a guy who owns a grand jury,” Napolitano warned on Thursday’s installment of Fox & Friends. “Bob Mueller owns two grand juries—one in Virginia and one in Washington, D.C. Look, the president is convinced he’s done nothing wrong. But the president couldn’t possibly know what Bob Mueller knows about the case—the thousands of documents he’s seen and the hundreds of witnesses that he and his team have investigated. This is what we call a perjury trap…

“If he answers, and he answers the way we know he likes to answer—where he doesn’t always use, most respectfully, an economy of words—he’s going to give them an opportunity to trip him up… You can’t talk somebody out of charging you with a crime if they’re determined to do it… It’s a very, very dangerous environment… When you go to talk to them, you make it worse.”

In their chats in recent months, the judge and the 45th president occasionally have reminisced about their chance meeting in October 1986, when they found themselves sitting next to each other at a memorial service for a mutual friend.

The notorious Roy Cohn had brought them together.

Cohn’s death—at age 59 of AIDS, a diagnosis Cohn, a closeted gay man, denied to the end—had lured some 500 admirers to Manhattan’s Town Hall, including Rupert Murdoch, Barbara Walters, Roger Stone, and the leading lights of the Tammany Hall machine and the New York political and real estate establishments, according to The New York Times’ account of the event.

Cohn—a mythic and widely reviled figure of the Red-baiting McCarthy Era—had been Trump’s mentor and consigliere as the young real estate developer was becoming a tabloid gossip column celebrity with oft-hyped political ambitions.

Meanwhile, Napolitano, then a 36-year-old lawyer in private practice and a Ronald Reagan acolyte, had collaborated with Cohn on a couple of legal cases, and had joined forces with him to help Shirley Wohl Kram, President Reagan’s federal judicial nominee for the Southern District of New York, prepare for her Senate confirmation.

As the mourners, including Trump and Napolitano, ended the service by belting out “God Bless America,” Cohn’s favorite tune, it was the beginning of an unlikely friendship that is consequential three decades later.