Goblins and witches, monsters and Martians. Invaders of all kinds will come knocking on doors this Halloween, eager to scare. The evening before, Mischief Night, pranksters roam the dark. Probably the greatest Halloween prank ever took place 75 years ago on Mischief Night.

On October 30, 1938, Orson Welles and The Mercury Theatre on the Air aired an updated dramatization of H.G. Welles’s Mars-invades classic War of the Worlds. Radio Martians were on the march and in much of the East, thousands of listeners who missed or ignored the signals that this was a radio play panicked and took to the streets. Police and newspaper telephone switchboards lit up with callers, terrified listeners armed themselves, whole families fled in horror, and reportedly some people even considered suicide rather than face the awful prospect of the Martian death rays and the end of the world.

My father, age 14 at the time, recalls listening to the broadcast that night. He knew it was entertainment. But tens of thousands—perhaps millions—in the audience did not. It remains arguably the most widely known delusion in United States, and perhaps world, history. Many radio stations around the world will rebroadcast the original play this Halloween eve. On October 29, PBS’s American Experience will broadcast its own “War of the Worlds” documentary about the “panic broadcast.”

The New York Times front page story the next morning reported that “a wave of mass hysteria seized thousands of radio listeners throughout the nation…[leading them] to believe that an interplanetary conflict had started with invading Martians spreading wide death and destruction in New Jersey and New York.” But what made so many Americans so gullible? It was a case of the jitters, a nation primed to jump at the word “Boo!”

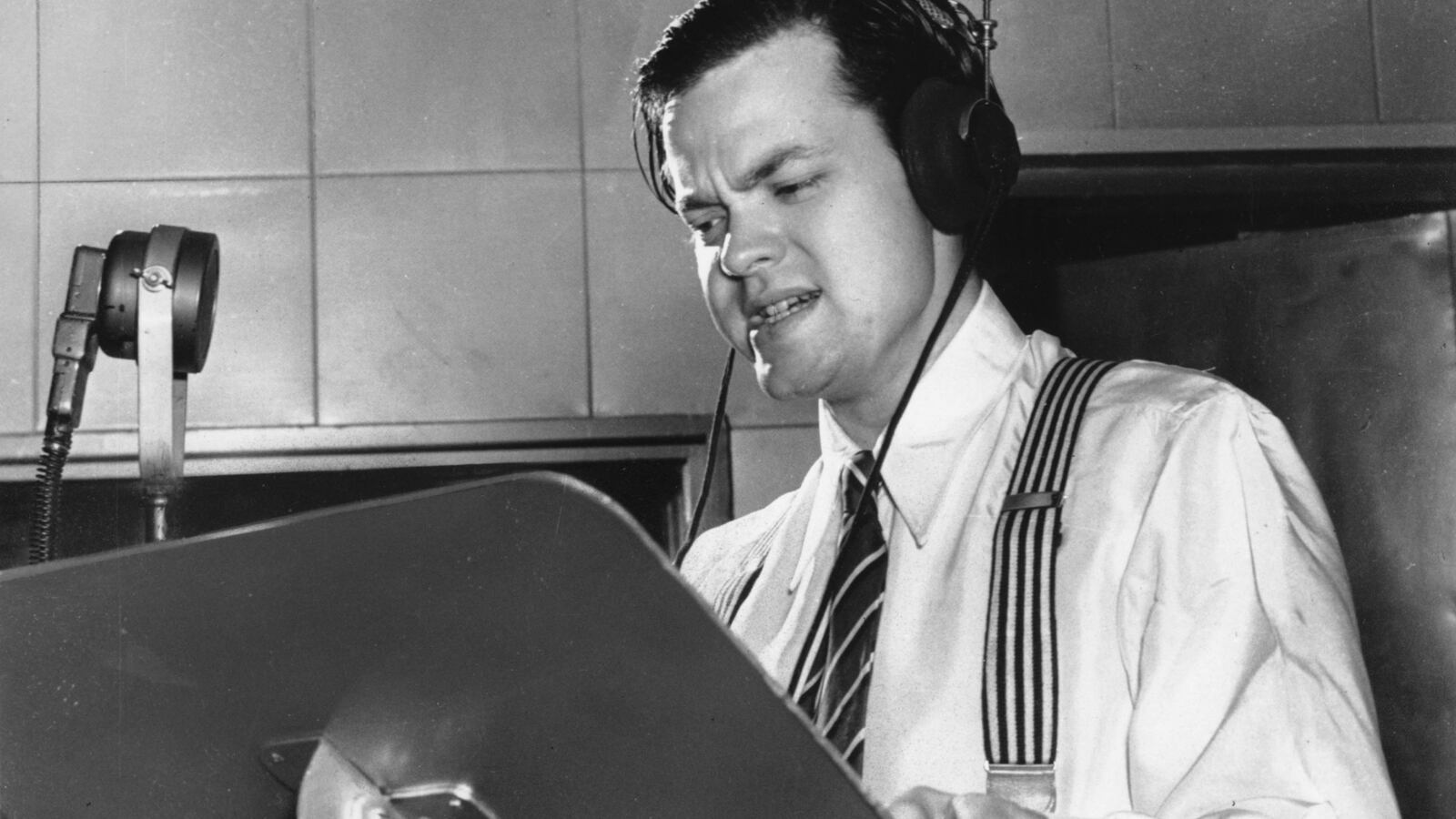

Few people knew better than Orson Welles how to spook an entire country. By then, 24-years-old, the handsome actor with his resonant baritone—a voice that would have made James Earl Jones envious—was already a recognized theater prodigy. He also had plenty of experience as a confidence man. Orphaned as a child, at age ten he ran off with the daughter of the Chicago-area family that had taken him in, living on the streets by doing song and dance numbers for change. At age 16, he used a small inheritance to travel to Europe and then, claiming to be a Broadway star, managed to win a role in a production at Dublin’s famed Gate Theatre.

Returning stateside to New York, he was soon starring in and mounting productions of his own. He worked with John Houseman, Aaron Copeland, Joseph Cotton and many others who were already famous or soon to be. In 1937 he founded a repertory company, Mercury Theatre, that quickly won a following for its modern stagings of classic dramas, like Julius Caesar set in then-fascist Italy.

Welles supported himself primarily with radio roles. This was a great time for someone with Welles’s talents, a flair for drama, a magisterial voice, and the ability to mount professional productions quickly within an allotted time slot.

Like 1950s broadcast television, after barely more than a decade as a consumer medium, radio was still new but had already swept into American homes. A nation of fewer than 120 million people spent most evenings gathered about 50 million radio sets by the late 1930s. They couldn’t get enough of live baseball and boxing, radio dramas, comedies, musical performances, political discussions, and news reports. Franklin D. Roosevelt was the first President to understand the power of the new broadcast medium. His fireside chats brought his reassuring “radiogenic” voice to millions of Americans still suffering from the Great Depression.

And listeners were also getting used to hearing the news live for the first tiem. Radio was there. In late 1936 they followed marathon coverage of the melodrama of Edward VIII’s abdication for his American lover, Wallis Simpson. That same year Americans heard their first ever live battlefield reports from the Spanish Civil War. The teary description by Herbert Morrison of Chicago station WLS of the fiery 1937 explosion that killed 36 people aboard the German zeppelin Hindenburg and one ground crewman in Lakehurst, New Jersey, still has the a vivid power to shake listeners.

Then in 1938 the mounting crisis presaging war in Europe burst over the airwaves into American homes. First came Adolf Hitler’s Anschluss in Austria; then a shooting war looked about to break out at any moment until three tense weeks of negotiations in September 1938 finally brought agreement in Munich to appease the Nazis with the annexation of Czechoslovakia. More radios were sold while British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and others met with Hitler than ever before.

A month later, war-tension nerves raw, rattled Americans were, as the neuroscientists say, primed for terror.

Welles had already appeared in many nationally broadcast radio dramas, including an anonymous starring role as Lamont Cranston in the immensely popular crime drama series The Shadow. He also began producing his own radio productions. In the summer of 1938 CBS gave the young talent unusual complete creative control to produce hour-long radio dramas that broadcast Sundays, 8:00 to 9:00PM. The Mercury Theatre on the Air brought together his repertory theater cast and crew, but rather than stage play readings on air, Welles and company adapted works of literature, most often novels, for the radio.

Welles and his writer Howard Koch, who would soon co-write the screenplay for Casablanca, lighted on H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, from 1897. It was one of the first novels of extraterrestrial invasion ever written, and it still feels fresh to readers today. But Welles and Koch decided to freshen it even further by moving the action from the Victorian English to the contemporary New Jersey countryside.

After Welles’ soothing introduction listeners were sent to the sparkling sounds of “Ramon Raquello and his Orchestra.” Flash! the music was interrupted by the first of a series of increasingly alarming news stories.

Reports came in that observatories had spotted explosions of “incandescent gas” on the planet Mars. After a brief musical interlude, the “station” set up a hook-up to the Princeton observatory where a reporter interviews astronomy professor Richard Pierson. Pierson (played by Welles) assures the listeners that there is nothing to be alarmed at, but then the first reports of a meteor impact arrive. Soon the reporters arrive at the tiny (and real) New Jersey farm village of Grover’s Mill to inspect a strange red hot object that plowed into the earth.

Before the reporter can say, Mars attacks! hideous fiends exit the space craft and begin shooting out death rays that incinerate scores of curious onlookers. The unstoppable Martians are on the move. The war of the world is on. An emergency government announcement appeared to give credence to the story. Before it was over, the Martians sweep aside American defenders and lay dozens of familiar places to waste before destroying New York City.

Nobody seemed to hear the second part of the program when, the lone survivor reports that after several months earthly disease finally did in the Martians. At the end, the sonorous Welles concludes with a little talk about Halloween.

Too late, listeners bombarded local police stations with calls. Phone company figures showed that local media and law enforcement agencies were inundated with up to 40 percent more telephone calls than normal during the broadcast. The next day the Times reported receiving 875 calls. The article claims, “One man who called from Dayton, Ohio, asked, ‘What time is the end of the world?’” Police converged on the real Grover’s Mill looking for the source of the trouble.

Listeners across the land had heard enough; they packed their bags and set off for safety. Many people in fact overlooked the extraterrestrial origin of the attack and assumed foreign armies, releasing poison gas, had invaded the United States. Volunteers showed up ready for battle. “We’ve got to stop this awful thing,” declared one courageous man.

Anecdotal reports from around the nation showed just how troubled America’s war-scare traumatized psyche was. A Princeton psychologist’s study estimated that approximately 6 million people listened to the program, of whom at least 1.2 million took it literally, while an unknown number who had not tuned in were caught up in the general hysteria.

The saying goes, “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty,” but the edge between vigilance and paranoia can be shockingly thin. History shows how Americans conditioned by news reports to fear those who might steal their freedom are to panic in terror. Thinking back on both the “War of the Worlds” panic and the all-too-real scenes of destruction and carnage of recent years, one of the lessons of living in the age of anxiety seems to be not to worry so much about alien invaders of any kind.

Trick or treat!