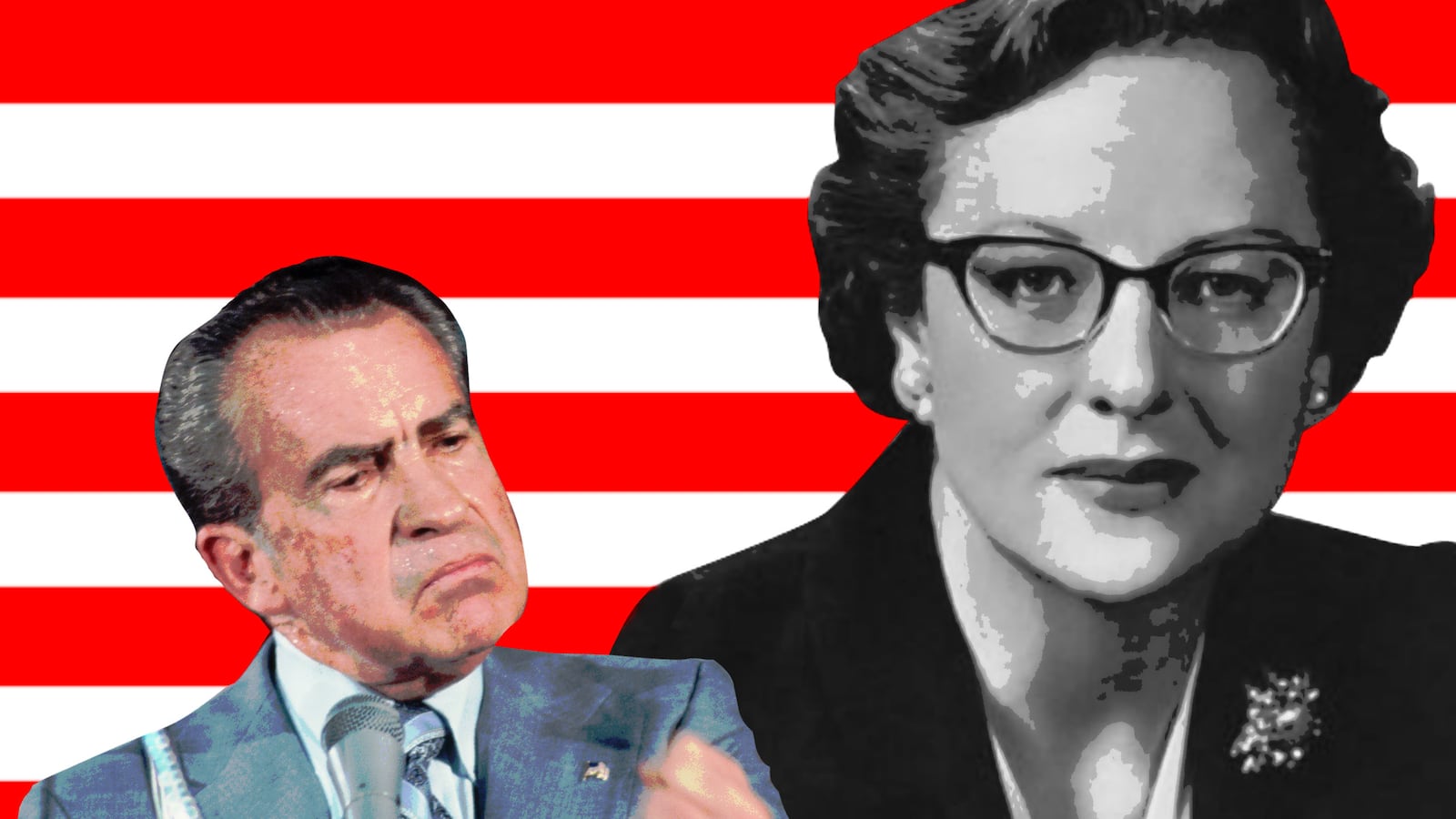

If he survives this ugly nomination fight where partisanship trumps ideology and qualifications—yet again—Judge Neil Gorsuch won’t be joining his daddy’s and granddaddy’s Supreme Court. America’s most exclusive fraternity used to be such a boys’ club that even when a Republican president floated the name of an impressive woman jurist, his trial balloon popped. Tellingly, in 1971, the American Bar Association advisory committee deemed Mildred Lillie, the first serious female Supreme Court possibility, “unqualified.”

That Richard Nixon tried to be the pioneering president to first name a woman to the highest court in the land appears to be another Nixon anomaly. The Red-baiting, liberal-hating, enemies-list-making Nixon also signed off on the Environmental Protection Agency, Affirmative Action, and an ever-expanding federal budget—while visiting Soviet Russia and Communist China.

Was he a closet feminist too?

Actually, these liberal moves demonstrate how “Tricky Dick” coped with the Sixties—and a Democratic Congress. Having been elected in 1968, Richard Nixon understood that unless he faced the major cultural, political, and social upheavals he would face defeat in 1972. When campaigning, this perpetually-needy politician shouted to women: “I want you! We need you!”

Once elected, Nixon agreed with his advisor Daniel Patrick Moynihan that, thanks to women’s liberation, “female equality will be a major cultural/political force in 1970’s.” Hoping to “make political hay,” Nixon directed his chief of staff H.R. Haldeman to “grab [the] ball on [the] women’s thing.”

Juggling, Nixon hired more women than his Democratic predecessors had but celebrated the traditional wife more enthusiastically, too. He said he was “proud of the women in our Administration who don’t hold office but hold the hands of the men who do.” He honored the Cabinet wives as a dozen mothers of 47 children—and as a dozen grandmothers to 45 more. Barbara Bush, the Republican National Chairman George H.W. Bush’s traditionalist helpmate, called one spousal outreach meeting Nixon hosted “the silliest thing in the world. He did it to make us feel part of things; instead of that, we felt like dolts—sitting in the back row.”

Similarly, while marginalizing his wife in the White House, Dick began pitching her as an equal to the outside world.

Pat Nixon visited day care centers—a bold move when many still considered them facilitators of maternal neglect. President Nixon also told Haldeman to “get a story out” that his wife and daughters were the “strongest advocates” for a female Supreme Court justice. He calculated that even if he failed, women would like having friends in the White House.

In October 1971, after two Nixon nominations to the Supreme Court failed, Nixon decided to ask the ABA’s committee to vet possible candidates before he nominated them. One front-runner was the California Court of Appeals judge Mildred Lillie.

Born in Iowa in 1915, Lillie grew up in California. Her formidable mother made her a moralist but failed to make her an artist. In college, Lillie realized “that if I had to rely upon my artistic talents to earn a living, I would probably spend the rest of my life on welfare.” Graduating Berkeley’s Law School in 1938, she faced the Great Depression and widespread discrimination. “I would never appoint a woman,” one senior lawyer admitted. “I’ve had a couple of women in this office, one of whom worked out fairly well, but the other ones created nothing but trouble.”

Eventually, Lillie found a job in private practice and in 1947 an appointment to Los Angeles Municipal Court. By 1958 this smart jurist often dismissed as “lady judge” began serving on the Court of Appeals. When she died in 2002, she was California’s longest-serving appellate judge for 44 years—and judicial officer for 56 years.

Lillie impressed Nixon’s aides. Attorney General John Mitchell declared: Lillie is “just conservative period.” Forever fighting liberals, Nixon sneered: “One thing about the woman conservative. These bastards can’t vote against her.” He added: “A conservative woman from California! God. That will kill them.”

Mitchell hoped the American Bar Association’s pre-approval would appear objective. “What the hell does the bar know about it,” Nixon replied. “Good God, I can take a bar examination better than any of those assholes.”

Surprisingly, despite Mildred Lillie’s impressive record, the twelve ABA representatives deemed her unqualified. They couldn’t conceive of a woman as colleague or judicial superior. Chief Justice Warren Burger, whom Nixon ordered to be a “good solider” and accept a female colleague, secretly lobbied members of the Committee to preserve the Court’s single-sex collegiality. Nixon’s former White House counsel John Dean later characterized the “disqualified” conclusion as “shameless gender discrimination.”

Forces to his right now blocked Nixon the reformer—or did they? John Jenkins’ 2012 book about the appointment of the successful nominee, William Rehnquist, suggests Nixon wanted credit for proposing a female justice without being stuck with one. It is hard to read any president’s mind, especially the Machiavellian Richard Nixon’s. Still, one possible tell remains. Nixon lacked the courage to tell his wife Pat that he appointed two men, William Rehnquist and Lewis Powell on October 21, 1971. When she objected, rather than blaming the ABA, he claimed no qualified woman shared his judicial philosophy of strict constructionism. Pat was furious. Dick dismissed her, saying “We tried to do the best we could Pat.” When Haldeman reported that the announcement “scored another ten strike,” the president added: “except for my wife, but boy is she mad.”

Mildred Lillie didn’t sulk. Dodging any Nixon-related taint may have relieved her. She became a California legend, with a favorite anecdote from her brush with national immortality. She enjoyed recalling that “the lanky and pleasant young man at the Justice Department who had carried her suitcase” became Chief Justice William Rehnquist.

Modern historians insist historical forces make history. Americans have certainly learned these last few months that individuals can force those forces in different directions. No one knows what kind of Supreme Court justice Mildred Lillie would have been. But, one thing is clear. The feminist revolution was greater than any one individual pioneer—or any twelve obstacles. A decade after Lillie’s rejection, Ronald Reagan appointed Sandra Day O’Connor to the Supreme Court. The locomotive of progress slowed but was neither derailed nor blocked, no matter who was president.