This is a story about truth and how, against all the odds, it can be discerned and defended against liars through individual acts of courage and genius. It is a story for all time and particularly our time, when totalitarianism bludgeons the truth tellers with renewed support.

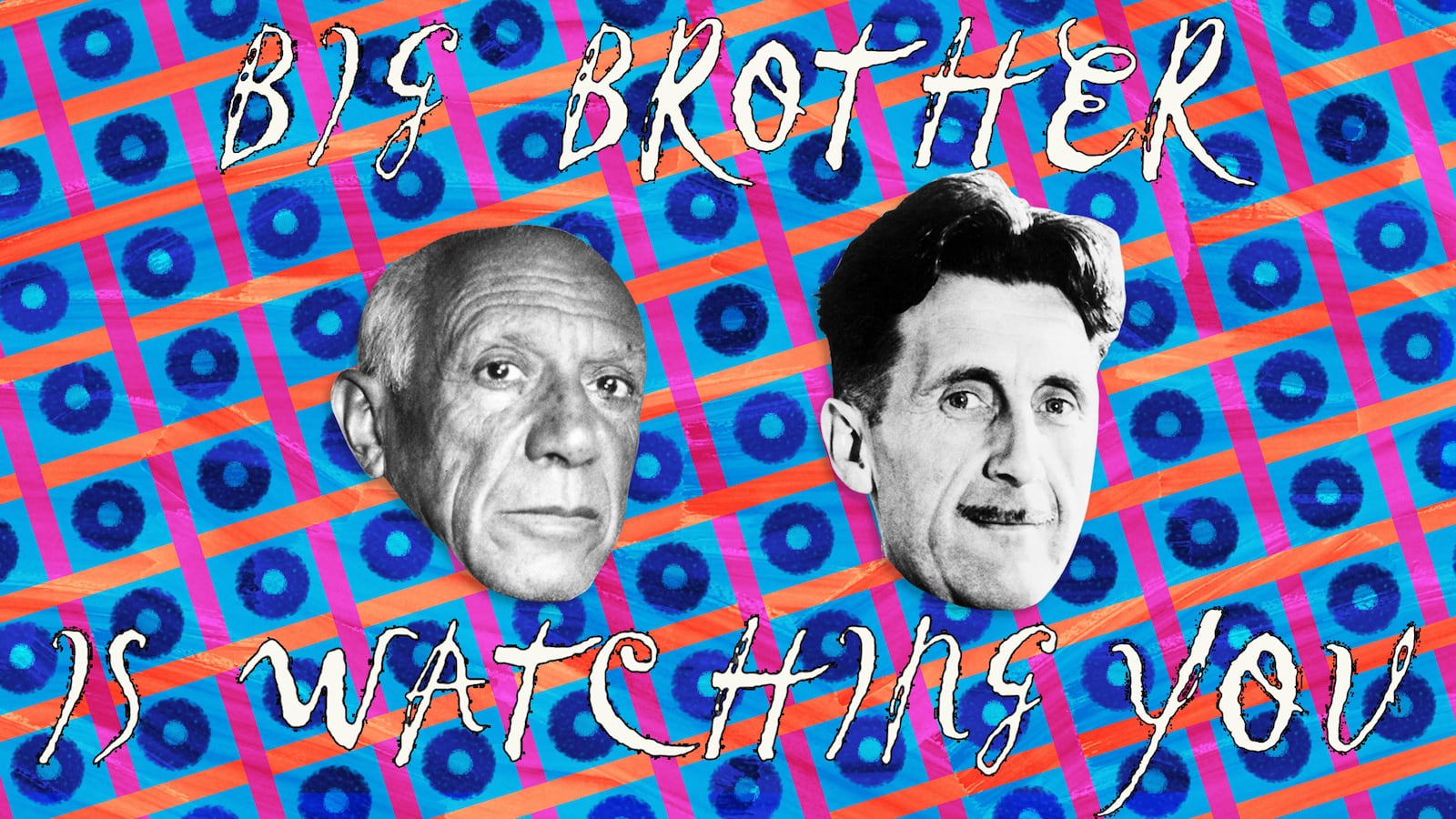

Pablo Picasso and George Orwell never met. But each of them, reaching the heights of their powers, looked at the same events in the same place at the same time, 80 years ago, and used their art to expose the true face of totalitarianism. At the time they were vilified for doing so.

Picasso produced his huge and wrenching masterpiece, Guernica, named for the northern Spanish city that was the first European city to be carpet-bombed. Orwell produced Homage to Catalonia, his gimlet-eyed record of fighting in the Spanish Civil War in which he nearly died.

Spain, Orwell discovered, “was a pawn in an enormous struggle that was being fought out between two political theories.” He fought with the republican government forces against the fascists but in the course of several battles realized that the republicans were being manipulated by Moscow and that “the Communists stood not upon the extreme Left but upon the extreme Right.”

The error—made by many thousands of European and American volunteers fighting with the republicans—was to believe that the forces opposing Generalissimo Franco’s fascists were naturally on the side of the angels simply because they were anti-fascist. As Orwell himself was swiftly disabused of this idea he came to the core revelation of his political life—that the true evil was totalitarianism, no matter what uniform it wore or what language it spoke.

Eventually that revelation shaped his two literary masterpieces, Animal Farm and 1984. However, the most immediate and personal result was that Orwell, in Homage To Catalonia, had delivered a message that nobody wanted to hear. In London his old socialist friends disowned him. Many of them were in thrall to Moscow’s utopian propaganda that the struggle in Spain was for universal liberty, rather than the slavery that Stalin had in mind.

Picasso was in a different kind of trap. When Guernica was exhibited in the U.S. the American Right labeled it “Bolshevist art controlled by the hand of Moscow.” In fact, Picasso did not join the French Communist Party until 1944, when Paris was liberated from the Nazis. Political theory had nothing to do with the raging art that drove Guernica.

On the afternoon of April 27, 1937, successive waves of German and Italian bombers dropped a combination of bombs on Guernica carefully designed to kill, maim and terrorize the civilian population—they included fragmentation bombs that eviscerated people and incendiaries burning at 2,500 degrees centigrade that turned the city into a fireball. People who fled into the hills were strafed with machine guns. More than 1,600 people died and nearly 1,000 more were injured.

Seen in the perspective of what followed, Guernica was a calculated forewarning to the world that total war now included the mass slaughter of civilians. Picasso’s canvas was more than 25 feet wide and eight feet deep. Within this space every figure—including a bull, a horse, a mother with a dead child, was eviscerated. Limbs, fingers, skulls interlocked in a gruesome dance of death. What Picasso took from the atrocity was intensely personal: the people of his native country had become the cannon fodder of a new order in Spain. Franco, abetted by Hitler and Mussolini, would rule by terror.

Guernica was exhibited in London before being shipped to the US. Critics were divided. As a commentary on war some ranked it with Goya’s rending account of the savagery of the Napoleonic wars. But the hand of ideology also surfaced. The critic Anthony Blunt called the painting “hopelessly obscure, its meaning elusive.” Unknown to anyone then, Blunt was a Soviet sleeper agent, unmasked only in 1979 as the long-sought Fourth Man in an espionage ring—his rejection of Guernica was the Stalinist party line conveyed as aesthetic distaste.

In America, when Guernica arrived in 1939, the reverse camp went on the attack. When it was exhibited in San Francisco an extreme right wing group named Sanity in Art savaged it as part of its campaign to “fight foreign influence” and dismissed it as left-wing propaganda. In Chicago, a hotbed of America Firsters who thought Europe should be left to be blitzed into oblivion, the Herald and Examiner, reflecting widespread conservative hostility toward Picasso, pushed the mantra that he was a tool of Moscow. Other papers across the country sang the same tune.

Part of Picasso’s America problem was not political. It was that the philistines had no understanding of modern art or, particularly, of Picasso’s pre-eminence. A newspaper in California said Guernica was “cuckoo art.” Another said it was “revolting” and “bunk.”

But it was different in New York. On November 15, 1939 the first retrospective of Picasso’s work opened at MoMA. Alfred Barr, the director of MoMA, had long persisted in assembling a show that he felt would finally establish Picasso as a giant of twentieth century art. Guernica provided the natural climax to the succession of galleries, a fusion of anguish and frightening beauty.

The show was the equivalent of a modern blockbuster—60,000 people saw it. With Europe now at war Picasso agreed that MoMA would be Guernica’s sanctuary until such time that he deemed it could return to Europe. That was where I first saw it, in 1963. It was the first thing I headed for, as did many first-time visitors to MoMA.. Here was the ultimate proof that reproductions can never prepare you for the impact of the real thing. It was not just the size. The canvas had an almost audible power—a great primal scream of agony and, at the same time, of outrage.

Guernica was finally returned to Spain in 1981, when the country had recovered its footing as a maturing democracy.

It took Orwell a lot longer to become recognized as the literary giant he was.

Reading Homage to Catalonia is to follow Orwell as his political education is forged day by day in war. The insights—and aphorisms—accumulate through intimate and painful experiences. This is what separated him from the socialists and communists in London—his previous milieu—whose beliefs came not from battlefields but from the comfortable groves of academe and Bloomsbury, where a number of upper class covert Soviet agents like Anthony Blunt mingled among the gullible subtly shaping opinions. carefully nurtured by covert Stalinist agents.

Outwardly Orwell (whose real name was Eric Blair) had the manners of Bloomsbury, of what he himself called “the lower upper class.” He spoke with an accent shaped by an education at the toffs’ academy, Eton and by working in the colonies (Burma) as a junior administrator. Inwardly he found this class repugnant. In Spain he noted the “Fat prosperous men, elegant women and sleek cars” of Barcelona but at the front line he discovered something far more admirable: “Many of the normal motives of civilized life—snobbishness, money-grubbing, fear of the boss, etc. —had simply ceased to exist. The ordinary class-division of society had disappeared to an extent that is almost unthinkable in the money-tainted air of England.”

But this wonderment is followed by cool reality: “Of course, such a state of affairs could not last. It was simply a temporary and local phase in an enormous game that is being played over the whole surface of the earth.”

Other people could reach the same conclusions, and feel them as strongly. Only Orwell had the mastery to turn feelings into prose of devastating directness—a quality he referred to as “intellectual brutality.”

Too brutal for some of his erstwhile fellow journalists.

The most widely-read and influential of British socialism’s publications was the weekly New Statesman. The editor, Kingsley Martin, asked Orwell to review one of the first books about the Spanish Civil War, Spanish Cockpit. It was written by Franz Borkenau, once an Austrian communist who worked for the party’s doctrinal police, the Comintern, in Moscow—until he realized that Stalin’s main interest was in tyranny. He fled to exile in Mexico and Panama and then went to Catalonia, ahead of Orwell, to write about the war.

Like Orwell, Borkenau had seen the big game for what it was and decided that Stalinism and fascism were indistinguishable in style and method. Orwell’s review endorsed Borkenau’s conclusion, citing his own experiences.

Martin rejected the review. He told Orwell: “it too far controverts the political policy of the paper. It is very uncompromisingly said and implies that our Spanish correspondents are all wrong.”

In 1943, when the outcome of World War II was still uncertain, Orwell wrote a postscript to Homage to Catalonia. He nailed the mindset that Martin had shown:

“In Spain I saw newspaper reports which did not bear any relation to the facts…I saw newspapers in London retailing these lies and eager intellectuals building emotional superstructures over events that had never happened. I saw, in fact, history being written not in terms of what happened but of what ought to have happened according to various party lines.”

He was equally unforgiving of the right.

It was troubling then to look back at those who had openly sympathized with German fascism and wonder why. Orwell compiled a list of them that included William Randolph Hearst, Ezra Pound, Father Coughlin, the Mufti of Jerusalem and Jean Cocteau. He was amazed at their diversity. But he had an explanation: “They are all people with something to lose, or people who long for a hierarchical society and dread the prospect of a world of free and equal human beings.”

In many cases what they had to lose, in their minds, was their security in a social order giving them privileges they thought should be permanent. If they thought this system was in jeopardy they were prepared to trade freedom for order. Orwell pointed out that it is always the propagandist’s first job to persuade people that their freedom is under threat when it is really the people pushing this line that intend to take away the freedom.

Orwell was describing a state of mind that was made disreputable in his time by the four versions of totalitarianism, German, Russian, Italian and Japanese, that jointly devastated the world. Now it turns out that the bad odor was not permanent. Totalitarianism simply hibernated until another age beckoned it to return.

Today, in Russia, Turkey, Hungary and Poland politicians “who dread the prospect of a world of free and equal human beings” are, in various degrees, either seeking or already holding power.

In Europe, ironically, Germany is seen as the best hope for defending the postwar compact of progressive democracies. Chancellor Angela Merkel lived for the first 35 years of her life in the Orwellian state of East Germany where every third person was employed to spy on the other two. That gives her an instinctive recognition of ideological cant. In Britain, Orwell would surely recognize in Jeremy Corbyn, the Labour Party leader, the same counterfeit socialism he exposed in Spain; Orwell would see a man who is suckered by Vladimir Putin, came to power on a tide of proletarian xenophobia and tolerates anti-Semitic lieutenants.

Of Donald Trump’s many disorders it is his authoritarian streak that is most natural to him. Anything requiring study and thought is tiresome. He has little interest in ideology. The constitution is not something to be honored but flouted. Always a scofflaw, his pardoning of Sheriff Joe Arpaio was a clear message that loyalty to him mattered more than criminality. Those of his former operatives now in the crosshairs of the Mueller investigation got that message: make no deals and I will make sure you don’t end up in jail.

As he blunders from crisis to crisis Trump is finally discovering and using the powers that are singular to his office, like pardons, that give him the results he wants. He now knows beyond any doubt what every would-be demagogue before him has understood: truth is a nuisance and lies build a fortress. As he proceeds, his body and face language more and more resemble those of the most thespian of the twentieth century’s dictators, Benito Mussolini. The hunched shoulders, the jutting jaw, the popping eyes are all so jarringly reminiscent of Il Duce.

Some made the mistake of seeing Mussolini as a bit of a joke. What happened to Italy under him was no joke. And Trump is no joke. We must hope that what eventually will destroy him is a simple but elegant line from Homage to Catalonia: “However much you deny the truth, the truth goes on existing.”