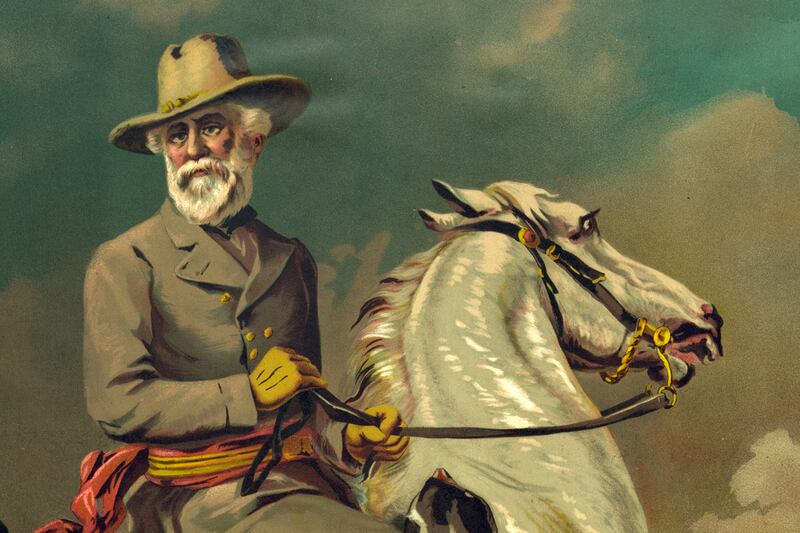

In October 1859, Brevet Colonel Robert E. Lee,* commanding the Second U.S. Cavalry, in Texas, was home on leave, laboring to untangle the affairs of his late father-in-law’s estate. Despite a brilliant military career—many thought him the most capable officer in the U.S. Army—he was a disappointed man. Nobody understood better than Lee how slowly promotion came in this tiny army, or knew more exactly how many officers were ahead of him in the all-important ranking of seniority and stood between him and the seemingly unreachable step of being made a permanent full colonel. He did not suppose, given his age, which was 52, that he would ever wear a brigadier general’s single star, still less that fame and military glory awaited him, and although he was not the complaining type, he often expressed regret that he had chosen the army as a career. An engineer of considerable ability—he was credited with making the mighty Mississippi navigable, which among other great benefits turned the sleepy town of Saint Louis into a thriving river port—he could have made his fortune had he resigned from the army to become a civil engineer. Instead, he commanded a cavalry regiment hunting renegade Indians in a dusty corner of the Texas frontier, and not very successfully at that, and was now home, in his wife’s mansion across the Potomac from Washington, methodically uncovering the debts and the problems of her father’s estate, which seemed likely to plunge the Lees even further into land-poor misery. Indeed, the shamefully run-down state of the Arlington mansion, the discontent of the slaves he and his wife had inherited, and the long neglect of his father-in-law’s plantations made it seem only too likely that Lee might have to resign his commission and spend his life as an impoverished country gentleman, trying to put things right for the sake of his wife and children.

He could not have guessed that an event less than seventy miles away was to make him famous—and go far toward bringing about what Lee most feared: the division of his country over the smoldering issues of slavery and states’ rights.

Harpers Ferry, Sunday, October 16, 1859

Shortly after eight o’clock at night, having completed his preparations and his prayers, a broad-brimmed hat pulled low over his eyes, his full white beard bristling like that of Moses, the old man led eighteen of his followers, two of them his own sons, down a narrow, rutted, muddy country road toward Harpers Ferry, Virginia. They marched silently in twos behind him as he drove a heavily loaded wagon pulled by one horse.

The members of his “army” had assembled there during the summer and early autumn, hiding away from possibly inquisitive neighbors and learning how to handle their weapons. John Brown had shipped to the farm a formidable arsenal: 198 Sharps rifles, 200 Maynard revolvers, 31,000 percussion caps, an ample supply of gunpowder, and 950 pikes.

For three years, from 1855 through 1858, a group of Free Soilers under the “command” of “Captain” Brown (or “Osawatomie Brown,” as he was called after his heavily fortified Free Soil settlement) fought pitched battles against “Border Ruffians” (as the pro-slavery forces were known by their enemies), in one of which his son Frederick was killed. Brown achieved fame bordering on idolatry among abolitionists in the North for his exploits as a guerrilla fighter in Kansas, culminating in a daring raid during the course of which he liberated eleven slaves from their masters in Missouri and, evading pursuit despite a price on his head, transported them all the way to freedom across the border in Canada in midwinter.

The object of his raid was the U.S. Armory at Harpers Ferry, where 10,000 military rifles a year were manufactured and more than 100,000 were stored. Its capture was certain to create a nationwide sensation, and panic in the South; but although Brown was a meticulous planner, his intentions after he captured the armory were uncharacteristically vague. He hoped the act itself would encourage slaves to join his cause, and intended to arm them with rifles if they came in large enough numbers; certainly his intention, once they were armed, was to lead them into the Blue Ridge Mountains, from which they could descend from time to time in larger and larger numbers to liberate more slaves: reenacting the raid into Missouri on a grander and growing scale. When he struck, Brown wrote, “The bees will begin to swarm.”

Careful as his preparations had been, Brown had perhaps waited too long before striking, with the result that his usual energy and decisiveness in action seem to have deserted him just when they were most needed. Unlikely as it may seem, he may have come to believe it would be sufficient to “stand at Armageddon and . . . battle for the Lord,” and the rest would follow. If so, he was underestimating the anger his raid would cause among the 2,500 people who lived in or near Harpers Ferry, or the alarm it would create in Washington, D.C., less than seventy miles away as the crow flies.

His first moves were sensible enough, given the small number of his force and the sprawling size of the armory. Two of his men cut the telegraph wires, while others secured the bridges over the Potomac and the Shenandoah rivers—Harpers Ferry was on a narrow peninsula, where the rivers joined, and not unlike an island—thus virtually isolating the town. Brown took prisoner the lone night watchman at the armory in the brick fire-engine house, a solid structure that he made his command post, then sent several of his men off into the night to liberate as many slaves as they could from nearby farms and bring their owners in as hostages. The western part of Virginia was not “plantation country” with large numbers of field slaves, but Brown had done his homework—one of his men had been living in Harpers Ferry for over a year, spying out the ground, and even fell in love with a local girl who had borne him a son.

Brown was particularly determined to capture Colonel Lewis W. Washington, a local gentleman farmer and slave owner on a small scale, the great-grandnephew of President Washington, and to have the ceremonial sword that Frederick the Great had presented to George Washington placed in the hands of one of his black followers as a symbol of racial justice. Colonel Washington (his rank was an honorary one) was removed in the middle of the night from his rather modest home, Beall-Air, about five miles from Harpers Ferry, and delivered to Brown in his own carriage, along with a pair of pistols that Lafayette had given George Washington, the sword from Frederick the Great, and three somewhat puzzled slaves.

More slaves were soon brought in, and armed with pikes to guard their former owners in the engine house—most either accepted these weapons reluctantly or refused to touch them. Brown now had thirty-five hostages and possession of the armory, but the slave uprising on which he was counting did not take place, and during the night, one by one, things started to go wrong.

*****

On October 17, John W. Garrett, the president of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, telegraphed President James Buchanan, as well as the governor of Virginia and the commander of the Maryland Volunteers, “that an insurrection was in progress . . . in which free negroes and whites were engaged.”

In the mid-nineteenth century presidents were by no means as insulated from the communications of ordinary citizens as they are today, and not a few presidents still opened their own mail and read their own telegrams. At the same time, the president of a major railroad was a person of considerable importance, so it is not surprising that Garrett’s message to President James Buchanan reached him without delay early in the morning on October 17 or that he acted on it immediately.

Buchanan … rapidly set in motion as many troops as possible: detachments of regular army infantry and artillery from Fort Monroe, Virginia, and a company of U.S. Marines from the Navy Yard under the command of Lieutenant Israel Green, the only troops available in Washington, were ordered to proceed by train at once to Baltimore and from there to Harpers Ferry, while uniformed companies of the Virginia and Maryland militias (the Hamtramck Guards, the Shepherdstown troop, the Jefferson Guards) had already begun to move into Harpers Ferry and were exchanging fire with John Brown’s outnumbered followers, along with a sizable number of armed and angry citizens and “volunteers,” or vigilantes.

Buchanan’s secretary of war, John B. Floyd, was not efficient … but he had the good sense to realize that somebody needed to be in command of all these forces converging on Harpers Ferry, and that the right man for the job was at his home in Arlington, just across the Potomac River from Washington.

Robert E. Lee and his wife had inherited the imposing white-pillared mansion that is now the centerpiece of Arlington National Cemetery in 1857 from her father, George Washington Parke Custis, the stepgrandson and adopted son of George Washington. The Arlington property alone comprised 1,100 acres, with a slave population of sixty-three, while two other plantations in Virginia brought the total number of Custis slaves to nearly 200. Custis’s management of his plantations, never his first interest—even a sympathetic fellow southerner described him as “a negligent farmer and an easy-going master”—had further slackened with age and infirmity. The Arlington mansion, while it was something of a museum of George Washington’s possessions (including the bed he died in), was leaking and in need of major, expensive repairs; the plantations were poorly farmed; and the slaves, who had been given to understand that they would be freed on Custis’s death, found instead that their release was contingent on the many other poorly drafted obligations in his will, which looked as if it might drag itself through the courts for years, keeping them in bondage indefinitely.

That this did not make for a happy or willing workforce was only one of the many problems that faced Lee, who, much against his own desire, had taken leave after leave from his post as commander of the recently formed Second U.S. Cavalry at Camp Cooper, Texas, a rough frontier outpost on the Clear Fork of the Brazos River, to devote himself to bringing some kind of order to his father-in-law’s estate. Much as Lee might wish he were back in Texas with his troopers chasing bands of Comanche marauders on the frontier, his sense of obligation and duty to his family kept him at Arlington, “trying to get a little work done and to mend up some things,” as he wrote to one of his sons, adding, “I succeed very badly.”

If so, it was one of the few examples of failure in the life of Robert E. Lee. One of the rare cadets to have been graduated from the U.S. Military Academy with no demerits, he had joined the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which in those days got the best and the brightest of cadets, and undertook successfully some of the largest and most difficult public projects of his time, including a safe deepwater channel on the Mississippi that opened up Saint Louis to shipping and caused the mayor of that city to hail him grandly as the man who “brought the Father of the Waters under control.” His service in the Mexican War was at once heroic and of vital importance; his “gallantry” won him universal admiration, as well as the confidence and friendship of General Winfield Scott, who singled Lee out for special praise to Congress.

Lee was later appointed superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy; his leadership at West Point won him the confidence and praise of both the cadets and the War Department, as well as giving him an opportunity to take advantage of its library and study in exhaustive detail the campaigns of Napoleon—a scholarly interest that would pay dividends in the most unexpected way only seven years later when he would become celebrated as the greatest tactician in American military history, as well as “a foe without hate, a friend without treachery, a soldier without cruelty, a victor without oppression . . . a Caesar, without his ambition, Frederick, without his tyranny, Napoleon without his selfishness, and Washington, without his reward.”

Lee was happy enough to give up the Corps of Engineers for active soldiering, and Jefferson Davis, secretary of war (and future president of the Confederacy), was eager to have him as second in command of the newly formed Second Cavalry, for which Davis had long petitioned Congress to reinforce the American military presence on the frontier. For the next six years Lee’s military service was to be of the hardest kind, in places where there was nothing much except lonely space “to attract Indians . . .or to induce them to remain,” and from which he wrote to his wife on July 4, 1856, with a burst of sincere patriotism: “the sun was fiery hot. The atmosphere like the blast from a hot-air furnace, the water salt; still my feelings for my country were as ardent, my faith in her future as true, and my hopes for her advancement as unabated, as if called forth under more propitious circumstances.”

Secretary of War Floyd returned from the White House to his office to put in motion the forces that he and President Buchanan had decided to send to Harpers Ferry, and to summon Colonel Lee to the War Department at once. He scrawled a quick note to Colonel Drinkard, chief clerk of the War Department, to write out an order to Lee, which read: “Brvt. Co. R. E. Lee, Lt. Col. 2nd cavalry is assigned to duty according to his Brvt rank & will repair to Harper’s Ferry & take command of the troops ordered to that place. He will direct all the troops from Ft. Monroe to continue their route to that place, Harper’s Ferry. [signed] J. B. Floyd, Secretary of War.” Finding First Lieutenant J. E. B. (“Jeb”) Stuart of the First Cavalry in his waiting room, and since Stuart was actually staying with the Lees at Arlington, Floyd gave him the sealed envelope and asked him to deliver it personally to Lee. Stuart had been a cadet at West Point when Lee became superintendent, and was a close friend of one of Lee’s sons, Custis, who had been a classmate. A Virginian, Stuart was already a young officer of great promise, a natural horseman with a reputation for dash and bravery gained in countless clashes with Indians throughout the West, and for steady competence in the pro- and antislavery warfare of Kansas, during which he had briefly met John Brown in the process getting Brown to release a detachment of pro-slavery Missouri militiamen he had taken prisoner. Stuart, who would become a Confederate hero, a major general, and the greatest cavalry leader of the Civil War, was in civilian clothes—he was there on business, having invented and patented “an improved method of attaching sabers to belts,” for the use of which the War Department paid him $5,000, plus $2 for every belt hook the army bought, not a bad deal for a junior officer—and set off immediately to Arlington. Stuart must have overheard enough to know that there was a slave insurrection taking place at Harpers Ferry, and once he reached Arlington and handed Lee the envelope, he asked permission to accompany Lee as his aide. Lee was almost as fond of Stuart as he was of his own sons (two of whom would serve under Stuart in the coming war), and agreed immediately. They set off together at once for the War Department—such was the urgency of the message that Lee did not even pause to change into uniform.

Floyd filled both officers in on what he knew—the president of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was already criticizing the small number of troops being sent, and hugely overestimating the number of insurrectionists—then took them over to the White House, to meet with the president. President Buchanan quickly provided Lee with a proclamation of martial law to use in case he needed it (by now rumor put the number of armed insurrectionists at 3,000), and both officers left for the station, Stuart having borrowed a uniform coat and a sword.

Horror of a slave revolt resonated sharply for Lee—slave rebellion, with the inevitable massacre of white women and children, was a fear of every white southerner, even without the prospect of northern abolitionists and freed blacks seizing possession of a Federal arsenal to arm the slaves.

Lee and Stuart took a train for the Relay House, where the spur line to Washington met the main line from Baltimore to the West, but found that the marines had already left there. The president of the Baltimore and Ohio provided them with a locomotive, and Lee telegraphed ahead to order the marines to halt at Sandy Hook, on the Maryland side of the Potomac about a mile to the east of Harpers Ferry, where Lee and Stuart caught up with them around ten o’clock on the night of October 17, after a smoky, noisy ride standing on the fire plate of the locomotive between the engineer and the fireman. By midnight, Lee, Stuart, Lieutenant Green, and the marines (accompanied by Major W. W. Russell, a marine paymaster) were in Harpers Ferry, and Lee had already appraised the situation as being less serious than was feared in Washington. Learning from the militiamen that the insurrectionists and their hostages were in the fire-engine house of the armory, he quickly telegraphed to Baltimore to halt the dispatch of further troops and artillery, ordered the marines into the armory grounds to prevent any insurrectionists from escaping, and decided to assault the fire-engine house “at daylight.” He would have attacked at once, but feared that the lives of “some of the gentlemen . . . that were held as prisoners” might be sacrificed in a night assault.”

One can sense, even in Lee’s brief report after the event, the firm hand of a professional soldier taking over. With exquisite politeness, he offered the honor of forming “the storming party” to the commander of the Maryland Volunteers, who declined it with remarkable candor, saying, “These men of mine have wives and children at home. I will not expose them to such risk. You are paid for doing this kind of work.” The commander of the Virginia militia also declined the honor (referring to the marines as “the mercenaries”), as Lee surely guessed he would—a lesson for the future, if Lee needed one, about the value of state militias—and he therefore ordered Lieutenant Green to “take those men out,” which is what he probably wanted in the first place, since Green was a professional and the marines were well-trained, reliable regulars. Calmly, Lee surveyed the ground, moved the militiamen back out of the way, and sat down to write a message to the leader of the insurrectionists:

Headquarters Harpers Ferry

October 18, 1859

Colonel Lee, United States Army, commanding the troops sent by the President of the United States to suppress the insurrection at this place, demands the surrender of the persons in the armory buildings.

If they will peacefully surrender themselves and restore the pillaged property, they shall be kept in safety to await the orders of the President. Colonel Lee represents to them, in all frankness, that it is impossible for them to escape; that the armory is surrounded on all sides by troops; and that if he is compelled to take them by force he cannot answer for their safety.

R. E. Lee

Colonel Commanding United States Troops.

John Brown was a realist in military matters, and although it was not in his nature to surrender, he soon recognized that he was surrounded by superior numbers and that no slave uprising was going to save him. By noon on October 17, the volume of fire had driven him back into the armory’s fire-engine house, a stout brick building with oak double doors, and he had already made an attempt to negotiate, proposing to release his prisoners in exchange for the right to take his men across the Potomac into Maryland, from which he no doubt hoped they could reach Pennsylvania. The two men he had sent out under a white flag were taken prisoner—the militia and the volunteers were in no mood to honor a white flag—but he soon sent out three more, with dire consequences: despite the white flag they carried, one of them was shot and wounded, and Brown’s son Watson was mortally wounded by a bullet in his guts and dragged back into the fire-engine house.

Brown set his men to work knocking out firing ports to transform the fire-engine house into a makeshift fort, and lashed the big central doors with ropes so as to leave a gap of several inches to fire through. His spirits were undaunted, and his faith in his mission as firm as ever. Even his prisoners, Colonel Washington among them, had come to admire the old man, however strongly they deplored what he was doing. By mid-afternoon, men were falling on both sides—the mayor of Harpers Ferry was shot and killed; Brown’s son Oliver, firing through the gap in the doors, was mortally wounded; two more of Brown’s men were shot as they tried to swim across the river; and one of the men Brown had sent out under a flag of truce was dragged from the hotel where he was being held to the Potomac bridge by the mob and executed—his body fell into the river and drifted to a shallow pool where people used it as “an attractive target” for the rest of the day. It could still be seen for a day or two “lying at the bottom of the river, with his ghastly face still exhibiting his fearful death agony.”

Lee made his plans carefully. Now that the fire-engine house was surrounded by the marines, he was certain nobody could escape. He ordered Lieutenant Green to pick a party of twelve men to make the assault, plus three especially robust men to knock in the doors with sledgehammers, and a second party of twelve to go in behind them once the main door was breached, and made it clear that they would all go in with their rifles unloaded—in order to spare the hostages, the assault was to be made with bayonets; no shots were to be fired. Green did not even have a revolver— because his orders had come from the White House, he had assumed that his marines were urgently required for some ceremonial duty. They wore their dress uniforms, and he was armed merely with his officer’s dress sword, the marines’ famous “Mameluke” commemorating their assault on Tripoli, with its simple ivory grip and slim curved blade, an elaborate, ornamental, but flimsy weapon intended for ceremony rather than combat, instead of the pistol and heavier sword he would normally have worn on his belt going into battle. Major Russell, the paymaster, as a noncombatant officer, carried only a rattan switch, but being marines these officers were not dismayed at the prospect of assaulting the building virtually unarmed.

At first light J. E. B. Stuart was to walk up to the door and read to the leader of the insurrectionists—his name was assumed to be Isaac Smith— Lee’s letter. Whoever “Smith” was, Lee took it for granted that the terms of his letter would not be accepted, and he wanted the marines to get to “close quarters” as quickly as possible once that had happened. Speed— and the sheer concentrated violence of the assault—was the best way of ensuring that none of the hostages was harmed. The moment “Smith” had rejected Lee’s terms, Stuart was to raise his cap and the marines would go in.

As dawn broke Stuart advanced calmly to the doors carrying a white flag and Lee’s message. Through the gap he could see a familiar face, and the muzzle of a Sharps carbine pointed directly at his chest at a distance of a few inches—after being captured John Brown remarked that he could have wiped Stuart out like a mosquito, had he chosen to. “When Smith first came to the door,” Stuart would later write, as if he had met an old friend, “I recognized old Osawatomie Brown, who had given us so much trouble in Kansas.”

Lee’s message made no great impression on John Brown, who continued to argue, with what Stuart called “admirable tact,” that he and his men should be allowed to cross the Potomac and make their way back to a free state. Stuart got along well enough with his old opponent from Kansas— except for their difference of opinion about the legitimacy of slavery, they were the same kind of man: courageous, active, bold, exceedingly polite, and dangerous—and the “parley,” as Stuart called it, went on for quite some time, longer almost certainly than Lee, who was standing forty feet away on a slight rise in the ground, had intended. At last Brown said firmly, “No, I prefer to die here,” and with something like regret, Stuart took his cap off and waved it, stepping sideways behind the stone pillar that separated the two doors of the building to make way for the marines.

There was a volley of shots from the fire-engine house as the three marines with sledgehammers stepped forward and began to batter away at the heavy oak doors. Because Brown had used rope to hold the doors slightly open, the sledgehammers made no impression at first, merely driving them back a bit as the rope stretched. Green noticed a heavy ladder nearby, and ordered his men to use it as a battering ram, driving “a ragged hole low down in the right hand door” at the second blow. Colonel Washington, who was inside, standing close to Brown, remarked later that John Brown “was the coolest and firmest man I ever saw in defying danger and death. With one son dead by his side, and another shot through, he felt the pulse of his dying son with one hand and held his rifle with the other, and commanded his men with the utmost composure, encouraging them to be firm and to sell their lives as dearly as they could.” This admiration for John Brown as a man was to become a common theme in the South in the next few weeks: he had all the virtues southerners professed to admire, except for his opinion of slavery.

Colonel Washington cried out loudly, “Don’t mind us. Fire!” as the door splintered, and Lee, who recognized Washington’s voice, exclaimed admiringly, “The old revolutionary blood does tell.”

Lieutenant Green was first through the narrow, splintered opening his men had created in the door. The inside of the fire-engine house was already dense with smoke—in the days before the invention of smokeless gunpowder, every shot produced a volume of thick, acrid black smoke— but despite it he at once recognized Colonel Washington, whom he knew. Washington pointed to Brown, who was kneeling beside him reloading his carbine, and said, “This is Osawatomie.” Green did not hesitate. He lunged forward and plunged his dress sword into Brown, but the blade struck Brown’s belt buckle and was bent almost double by the force of the blow. Green took the bent weapon in both hands and beat Brown around the head with it until the old man collapsed, blood pouring from his wounds. As the marines followed Green in, led by Major Russell with his rattan cane, one of them was shot in the face, and another killed. The rest “rushed in like tigers,” in Green’s words; stepped “over their fallen comrades”; and bayoneted two of Brown’s followers, pinning one of them against the far wall. The others surrendered, and the fight was over in three minutes. Green would later remark that “a storming party is not a play-day sport,” which was no doubt true enough, but Lee had achieved his objective: none of the prisoners was harmed in the assault. Colonel Washington refused to leave the fire-engine house until he was provided with a pair of gloves, since he did not want to be seen in public with dirty hands.

Lee “saw to it that the captured survivors were protected and treated with kindliness and consideration.” Indeed, once the fire-engine house was taken, everybody seemed impressed by John Brown, rather than infuriated or vengeful. Lieutenant Green assumed he had killed Brown, but it soon appeared that the old man’s wounds were less serious than had been thought, and Lee had him carried to the office of the paymaster of the armory, where Brown soon recovered enough strength to hold what would now be called a “celebrity press conference” combined with some of the attributes of a royal audience. Lee courteously offered to clear the room of visitors if their presence “annoyed or pained” Brown, who, though in considerable pain, replied that “he was glad to make himself and his motives clearly understood,” a considerable understatement given what was to come in the next six and a half weeks, during which Brown would be transformed into a national hero and martyr, largely by the skill with which he played on public opinion in the North, and by his natural dignity and courage.

The small room was crowded. Brown and one of his wounded men, both lying on some blood-soaked old bedding on the floor, were surrounded by Lee; Stuart; Governor Wise of Virginia; Brown’s former prisoner the indomitable Colonel Washington; Senator Mason of Virginia, who in the near future would become the Confederacy’s “commissioner” in the United Kingdom; Congressman Vallandigham of Ohio and Congressman Faulkner of Virginia, among others; and perhaps more important than all of these, two reporters, one from the New York Herald and one from the Baltimore American, with their notepads at the ready. To everybody’s surprise, Brown allowed himself to be questioned for three hours, never once losing his self-control or the respect of his audience, and giving “no sign of weakness,” even though Lieutenant Green’s first thrust with his sword had pierced through him almost to his kidneys before striking his belt buckle.

Governor Wise perhaps spoke for everyone when he said of Brown, “He is a man of clear head, of courage, fortitude and simple ingenuousness. . . . He inspired me with a great trust in his integrity as a man of truth. He is a fanatic, vain and garrulous, but firm, truthful and intelligent,” unusual words to describe a man who had just stormed and captured a town and a federal arsenal, and was responsible, at least morally, for the death of four townspeople and one marine. Wise added, “He is the gamest man I ever saw,” a sentiment everybody seemed to share.

He was also the most eloquent. When Senator Mason asked him how he could justify his acts, Brown replied, “I think, my friend, you are guilty of a great wrong against God and humanity—I say it without wishing to be offensive—and it would be perfectly right in any one to interfere with you so far as to free those you willfully and wickedly hold in bondage. I do not say this insultingly.” When Mason asked him if he had paid his men any wages, Brown replied, “None,” and when J. E. B. Stuart remarked at this, a trifle sententiously, “The wages of sin is death,” Brown turned to him and said reprovingly, “I would not have made such a remark to you, if you had been a prisoner and wounded in my hands.”

Again and again Brown trumped his opponents. When asked upon what principle he justified his acts, he replied: “Upon the golden rule. I pity the poor in bondage that have none to help them; that is why I am here; not to gratify any personal animosity, revenge or vindictive spirit. It is my sympathy with the oppressed and the wronged, that are as good as you and as precious in the sight of God.”

Lee would later write that the ineptitude of Brown’s plan proved he was either “a fanatic or a madman,” and from the military point of view he was right: twelve of Brown’s eighteen men, including two of his sons, had been killed, and two (including himself) wounded. But in fact Brown’s plan had worked out triumphantly, though not in the way he had intended.

Lee ordered Lieutenant Green to deliver Brown to the Charles Town jail to await trial, but Brown was far from being a political prisoner in the modern sense; he was allowed to carry out from the very beginning an uncensored and eloquent correspondence with his admirers and his family. The initial reaction in the North was that he had given abolitionism a bad name by his violent raid, but that quickly changed to admiration— here was a man who did not just talk about ending slavery, but acted. Although his wounds obliged him to attend his trial lying on a cot and covered with blankets, Brown’s behavior during it transformed him into a hero and a martyr throughout the world except in the slave states.

Lee was glad to leave Harpers Ferry and return home, but after a few days there he was ordered back to organize the defense of the armory, since the growing storm of protest over Brown’s sentence had made Governor Wise fearful of a new attack on it, or of an attempt by armed abolitionists to free Brown—though Brown himself had discouraged all such attempts, convinced now that his martyrdom was part of God’s plan for the destruction of slavery. Lee, who above all things disliked emotional personal confrontations, was obliged to deal as tactfully as he could with the arrival in Harpers Ferry of Mrs. Brown, who wished to see her husband before he was executed. Mrs. Brown had come, accompanied by a few abolitionist friends, “to have a last interview with her husband,” as Lee wrote to his wife, explaining, “As it is a matter over which I have no control I referred them to General Taliaferro.” (William B. Taliaferro was the commander of the Virginia Militia at Harpers Ferry.)

The day of the execution, December 2, Lee was no more anxious to watch Brown hang than he had been to deal with Mrs. Brown, and took care to station himself with the four companies of federal troops from Fort Monroe, which had been sent by the president to guard the armory at Harpers Ferry at the request of Governor Wise. In his majestic biography of Brown, Oswald Garrison Villard—grandson of William Lloyd Garrison, the famous abolitionist and supporter of John Brown—mused, “If John Brown’s prophetic sight wandered across the hills to the scene of his brief Virginia battle, it must have beheld his generous captor, Robert E. Lee, again in military charge of Harper’s Ferry, wholly unwitting that upon his shoulders was soon to rest the fate of a dozen confederated states.”

But of course no such “prophetic sight” or “spiritual glance,” as Villard also imagined it, carried that far from the scaffold. The old man, who had arrived seated on his own coffin, in a wagon drawn by two horses, was as dignified and commanding a presence as ever—as he reached the scaffold, he remarked, looking at the line of the Blue Ridge Mountains, where he had hoped to shelter with the slaves he had freed and armed, and from which he had intended to raid from time to time to free more until a kind of human chain reaction brought an end to slavery, “This is beautiful country. I never had the pleasure of seeing it before.” Erect, serene, calm, he had to wait for twelve minutes with the noose around his neck while the Virginia militia tried clumsily to form up in ranks as a square around the gallows, without showing the slightest sign of trembling in his legs or of fear on his face; the fierce eyes, which countless people who knew him compared to those of an eagle, stared unblinkingly at more than a thousand witnesses to his execution before the hood was placed on his head.

Many in the ranks around the scaffold would die in the war that was coming, some of them rising to fame and high rank, one of them at least to lasting infamy. In command of a detachment of cadet artillerymen from the Virginia Military Institute in their uniforms of gray and red was Thomas J. Jackson, professor of natural and experimental philosophy and instructor of artillery, who was praying fervently for John Brown’s soul and who in just nineteen months would receive his nickname, “Stonewall,” at First Manassas—First Bull Run, in the North—and would go on to become Lee’s most trusted corps commander and lieutenant. Also among the troops drawn up to prevent Brown’s being rescued were Edmund Ruffin, a white-haired firebrand secessionist who was determined to see Brown die, had purchased some of the blades from John Brown’s pikes in order to send one to the governor of each slave state as a reminder of Yankee hatred of the South, and would fire the first shot on Fort Sumter; and, in the Richmond company of the Virginia militia, a private of dramatic appearance, eyes fixed on the figure on the scaffold and delighted to be part of a historic scene: the actor John Wilkes Booth, who in five years would become Lincoln’s assassin, and would himself have stood on a scaffold like Brown’s had he not been shot by a Union soldier.

Once it was north of the Mason-Dixon Line the train carrying Brown’s body—transferred to a new coffin that was not of southern origin or manufacture—was halted by huge crowds at every station along the way, until he was at last laid to rest before a giant boulder at his home in New Elba, New York, in the shadow of Whiteface Mountain.

Showers of meteors had marked Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, his trial, and his execution, prompting Walt Whitman, in a poem about Brown, to ask himself, “What am I myself but one of your meteors?” Thoreau too, described Brown’s life as “meteor-like, flashing through the darkness in which we live,” and Herman Melville, in The Portent, described Brown prophetically as the “meteor of the war.” It was Melville’s phrase that stuck, appropriately, since it would be only seventeen months between John Brown’s execution and the firing on Fort Sumter that brought about the war.

Whatever else Brown had done, the reaction to his death effectively severed the country into two opposing parts, making it clear to the South, even to moderates there who were searching for a compromise, that northerners’ tolerance for slavery was wearing thin. Until Brown’s death, the issues had been whether or not slavery would be extended into the “territories,” and the degree to which escaped slaves in the free states could be seized as property and returned to their owners. Now Brown had made the very existence of slavery as an institution an issue—in fact the issue.

Assigned temporarily to command the Department of Texas, Lee returned there in February 1860 to resume his pursuit of Mexican bandits and Comanche bands on the frontier. He did not dwell on his face-to-face meeting with John Brown, or on his own role in one of the most striking dramas in American history, but one senses in his correspondence with friends and family a growing alarm, intensified by his experiences at Harpers Ferry, at the speed with which the Union appeared to be unraveling. He was as little pleased with the extravagant demands of what he called, with the natural distaste of a Virginia aristocrat for the noisy and violent nouveaux riches of the great cotton plantations, “the ‘Cotton States,’ as they term themselves,” as with the strident hostility of the abolitionists toward the South. He was appalled at southerners’ talk about “the renewal of the slave trade,” to which he was “opposed on every ground,” and his experience of dealing with his father-in-law’s slaves had further soured his view of slavery as an institution. He regarded secession as “revolution,” dismissed it as silly, and “could anticipate no greater calamity for our country than a dissolution of our union.”

Robert E. Lee was a Virginian who had lived for over thirty years outside the South, except for brief periods at Arlington and his service in Texas. He was a cosmopolitan, who felt as much at home in New York as he did anywhere in the South; he was opposed to secession; he did not think that preserving slavery was a goal worth fighting for; and his loyalty to his country was intense, sincere, and deeply felt.

He was careful, amid the vociferous enthusiasm for secession in Texas once Lincoln was elected, to keep his opinions to himself, but in one instance, when asked “whether a man’s first allegiance was due his state or the nation,” he “spoke out, and unequivocally. He had been taught to believe, and he did believe, he said, that his first obligations were due Virginia.” This simple, old-fashioned point of view was to guide Lee through the next four years, during which he would become the foremost general, and indeed the figurehead, of a cause in which he did not completely believe.

He was still in Texas, the great moral decision of his life was still ahead of him, the country he loved was still—just—held together by bonds that were growing more strained with every day that passed, but already Lee was being forced to think about taking the same course as the man he had surrounded and captured at Harpers Ferry. In the short time the two men had spent together in the paymaster’s office in the armory at Harpers Ferry, they may not have recognized how much they had in common. The Virginia gentleman and the hardscrabble farmer and cattle dealer from New England were both deeply religious, both courageous, both instinctive warriors, both gravely courteous, both family men, both guided by deep and unquestioning moral beliefs. John Brown may have been, as Robert E. Lee believed, a fanatic and a madman (the first was certainly true, the second not at all), but like him Lee, too, despite his firm opinion that “obedience to lawful authority is the foundation of manly character,” would himself become, at last, a rebel—perhaps the greatest rebel of all.

*A “brevet” rank was honorary. Lee’s actual rank at the time was lieutenant colonel.

This article is excerpted from Michael Korda’s Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee and is reprinted with the permission of the author and the publisher, HarperCollins.