The 116th and 34th Congresses of the United States have a lot in common: tensions running high between political parties deeply divided on nearly every question; incendiary speeches made and personal barbs publicly thrown; and a disturbing number of bystanders, those so-called gentlemen of Congress (in the 34th, at least, the culprits were necessarily men) who accept no responsibility for the outrages happening around them.

But there is one major difference. In today’s Congress, these vicious ideological battles haven’t resulted (yet) in the near murder of a colleague on the Senate floor.

In May of 1856, America was a little less than five years away from the opening shots of the Civil War, but the conflict was already starting to feel inevitable. The seeds of discord that had been planted when the first slave ship arrived on the shores of the “new” land were finally beginning to bloom as the 34th Congress tackled the question of Kansas.

No one disputed that the territory of Kansas should become one of the newest states. The problem was whether slavery would be permitted or prohibited in its borders. The very premise of the question was an outrage to the anti-slavery Republicans, who thought this had been decided in 1820 with the Missouri Compromise, which established a boundary above which no state would be allowed to own slaves. Kansas was above the line.

But a new bill proposed to change that.

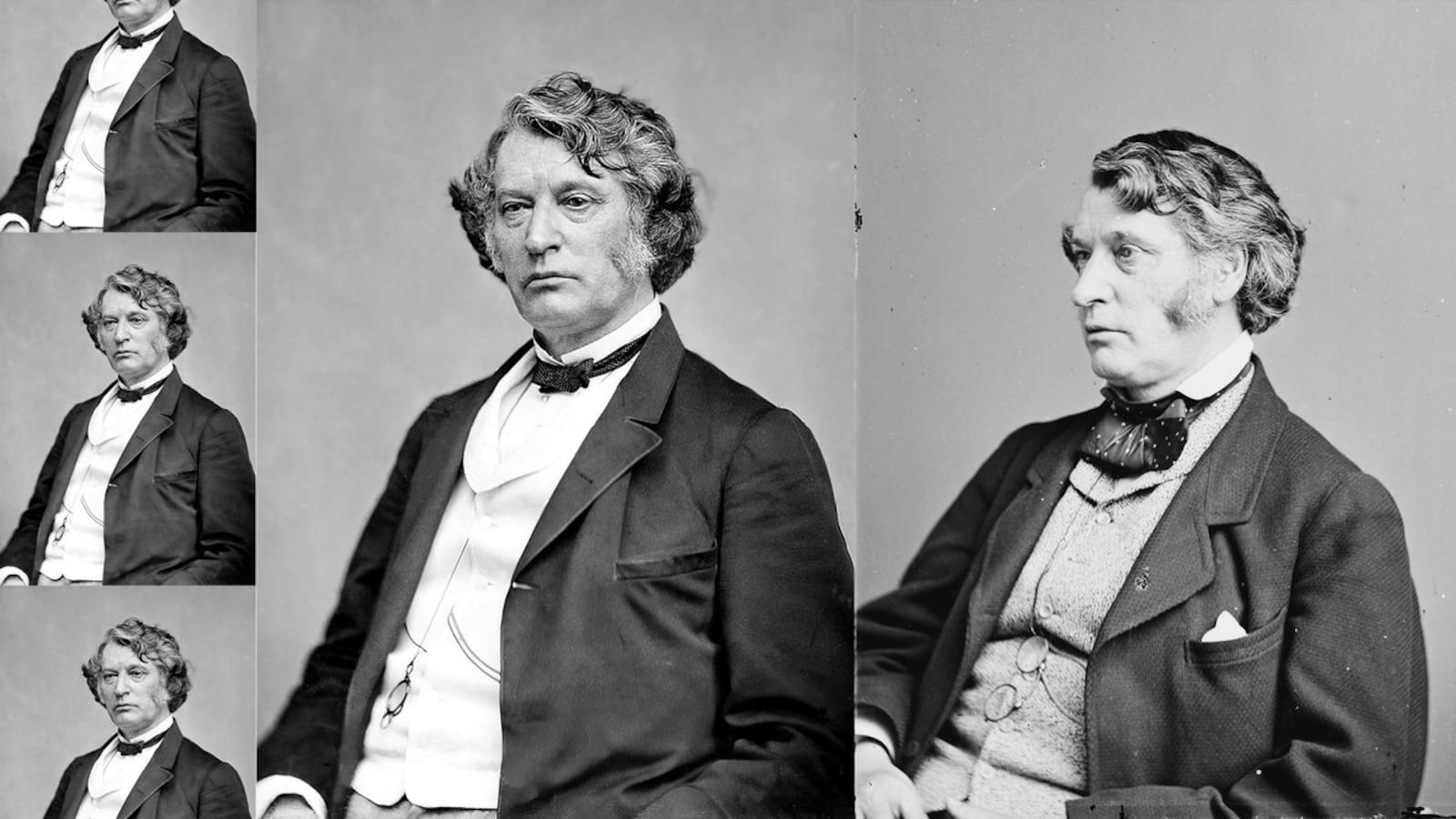

Senator Charles Sumner, an avowed abolitionist from Massachusetts, fought against it for a free Kansas with all of his rhetorical might by way of a two-day speech in which he attacked the men who upheld the institution of slavery for their “lust for power” and “depraved desire.” He called out two of his fellow senators in particular.

Congressman Preston Brooks took offense at the disparagement of his family—one of the senators Sumner insulted was his second cousin—and he met the words with his gold-tipped cane. In the vicious assault that took place on the Senate floor, Brooks nearly beat Sumner to death.

“Mr. Sumner, I have read your speech twice over carefully. It is a libel…”

The two men could not have been more different. Not only was there North versus South to contend with, abolitionist versus pro-slavery, Senate versus House of Representatives, but Sumner and Brooks were also temperamentally opposed.

Sumner had grown up committed to fighting for his cause and had even helped found the Free Soil Party that was dedicated to stopping the spread of slavery. Brooks had a history of violence, had been kicked out of college, and had been wounded in a duel by the time the 36-year-old South Carolinian found himself confronting the Senator from Massachusetts.

While the Kansas-Nebraska Act represented everything Sumner stood against, it also offered him the opportunity to make his first big mark since he was elected three years prior. He chose to do so via a speech, a very long speech, titled “The Crime Against Kansas” that spanned two days, five hours, and 112 pages.

When it came to making his impassioned plea for a free Kansas, Sumner was compelled to meet the offense of slavery with a few offenses of his own.

In his speech, he condemned the institution and called out the violence it incited that would lead to the period becoming known as “Bleeding Kansas.” But he took things one step further. His audience was shocked when Sumner began to speak about the culture of rape that permeated slavery.

“Just as today there are things that are widely known or assumed to be true by the public but understood to be off-limits to polite conversation, the intertwined nature of rape and slavery was one such verboten topic in the 1850s. But Sumner, in his first major speech as a senator, went there,” Ryan Grim writes in The Intercept.

Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas, a pro-slavery Democrat, had this to say about what he heard: “I cannot repeat the words. I should be condemned as unworthy of entering decent society, if I repeated those obscene, vulgar terms which have been used at least a hundred times in that speech.”

Sumner extended the sexual innuendo beyond just the institution as a whole, and specifically called out the authors of the proposed new act. Sumner particularly went after South Carolina Senator Andrew Butler, who wasn’t present in the chambers during those two days to hear his name besmirched.

Sumner said that Butler “has read many books of chivalry, and believes himself a chivalrous knight with sentiments of honor and courage. Of course he has chosen a mistress to whom he has made his vows, and who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight—I mean the harlot, slavery.”

To Brooks’s second-hand ears (he also wasn’t in the Senate chambers that day), they were fighting words.

It is indisputable that the South Carolina congressman wanted revenge for the insult Sumner lobbed against his family. But whether the incident that followed was purely an act of his own folly or whether he was used as a puppet of the party is still in dispute.

In All the Powers of the Earth, journalist Sidney Blumenthal argues that Brooks’ attack was masterminded by the “F Street Mess,” a group of powerful southern senators dedicated to upholding slavery.

Either way, Brooks was determined to seek his revenge. He thought about challenging Sumner to a duel, but egged on by two friends, he concluded that the gentlemanly face-off was too proper a response for the egregious offense. (Plus, there was Brooks’s complicated history with dueling, as his limp could attest). “Instead, he chose a light cane of the type used to discipline unruly dogs,” as a report by the United States Senate says,

On May 22, 1856, three days after the speech, Brooks walked into the Senate chambers at the end of session. He chivalrously waited for all of the women present as observers that day to leave the room, and then he approached Sumner, who was sitting at his desk preparing a pamphlet of his speech for distribution.

In a declaration worthy of Inigo Montoya, Brooks approached Sumner and said “Mr. Sumner, I have read your speech twice over carefully. It is a libel on South Carolina and Mr. Butler, who is a relative of mine.” He then raised the gold-tipped cane and landed a fierce blow on the Senator.

Sumner dropped to the floor and almost immediately lost his sight. He later said, “I no longer saw my assailant, nor any other person or object in the room. What I did afterwards was done almost unconsciously, acting under the instincts of self-defense.”

But he was incapacitated almost from the first blow and wasn’t able to put up much of a fight. Sumner dropped to the floor beneath his desk, while Brooks proceeded to relentlessly assault him. The desk was bolted to the ground and, instead of offering protection, proved to be a cage that kept Sumner in the perfect position for his attacker. Sumner eventually gathered his strength and rose, tearing the desk from the floor, but he was too weak to escape.

As he fled up the aisle, Brooks pursued him, getting in a few final beatings. Sumner allegedly gave one last groan and fell to a bloody heap on the floor. By this time, the cane was in pieces.

Brooks would later express no remorse for his actions. “Every lick went where I intended. I plied him so rapidly that he did not touch me,” he said.

During the assault several senators did try to intervene, but were met by the barrel of a gun wielded by Brooks’ two accomplices; others were reported to have egged Brooks on, shouting things like “Give the damned Abolitionist hell!”

Brooks would later contend that he stopped because he had accomplished his mission, but witnesses say he was eventually pulled off the senator, who by that time was near death.

Sumner faced a long recovery, and he wouldn’t return to the Senate full-time for three years. Brooks largely escaped censure. The Senate deferred to the House on his punishment, but the House couldn’t whip up the votes to have him ousted. He instead resigned, though he was quickly re-elected in the special election that followed.

In the eyes of Southerners and his Democratic party, Brooks was a hero. Several congressmen allegedly turned pieces of the broken cane into rings that they wore as necklaces in celebration and support of the attack.

But Sumner would be the victor in the end. Less than a year after the incident, Brooks would die from a sudden illness. While it would take two more years for Sumner to be well enough to return to his seat, he would remain there for another 15.

In the end, Brooks and the Southerners would be remembered as belonging to the wrong side of history, while Sumner never wavered in his commitment to the cause of abolition. After the Civil War, his mission continued as he took up proverbial arms once again, this time against the racist policies of Reconstruction.