In light of the recent discord over the Metropolitan Opera’s staging of John Adams’s The Death of Klinghoffer, consider another opera that will see a rare American performance at the Met on November 10. Almost 80 years ago, the controversy it raised came close to costing its composer his life.

The heroine of Dmitri Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk and her lover will once again hurtle to their Siberian doom in front of a New York audience on Nov.10. The opera is a dark and passionate tale of adultery and greed. Blood and murder will bestride the boards at the Met.

On a freezing January night in Moscow in 1936, in a performance by the Bolshoi, the ferocity and tragedy escaped from the stage to haunt the living.

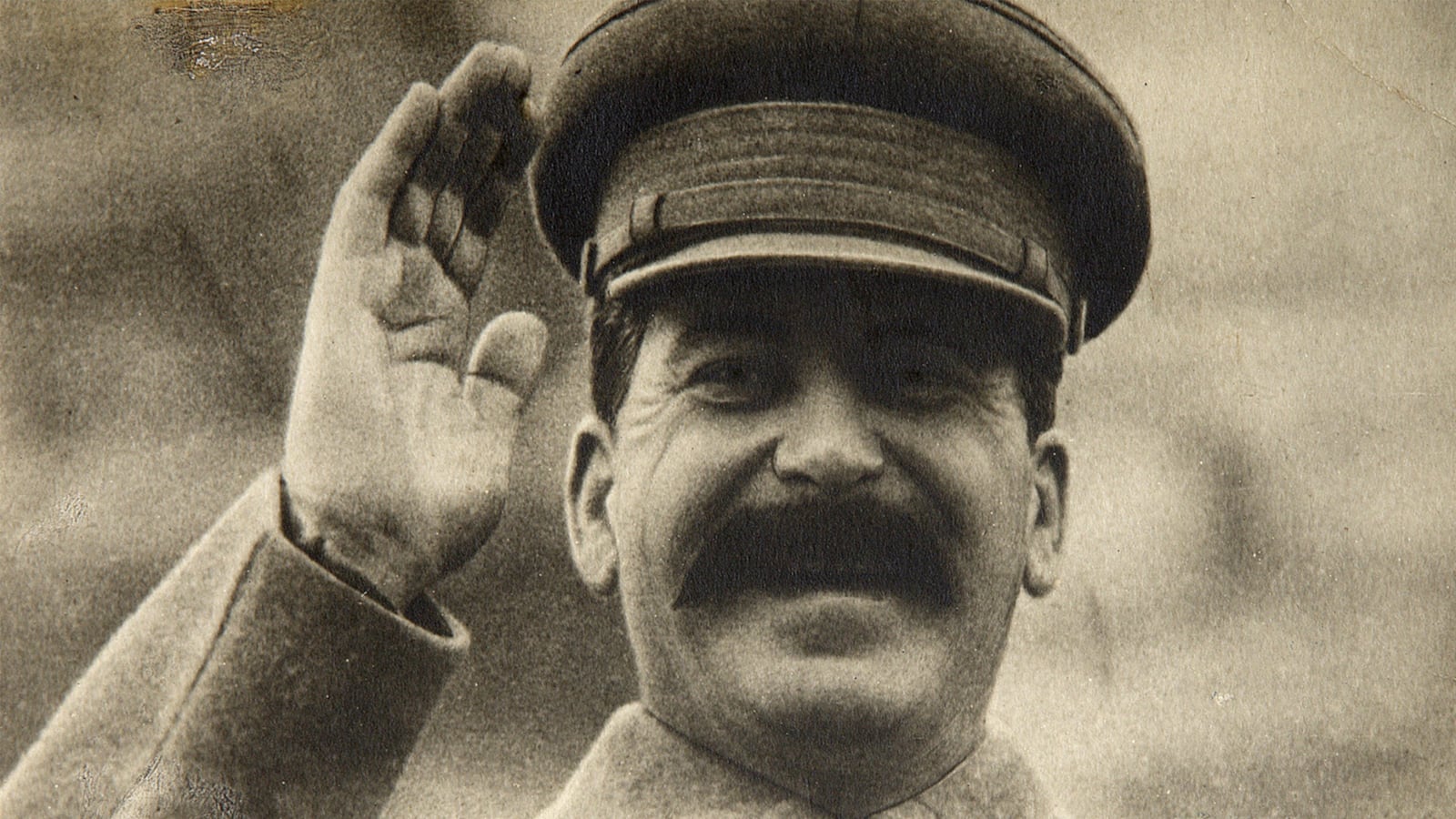

Joseph Stalin was in the audience. So was Shostakovich. The dictator walked out after the third act. The composer was seen to turn “white as a sheet.” He was due to leave Moscow that evening for concert performances in the far North. “Feeling sick at heart,” he wrote to a friend, “I collected my briefcase and went to the station. I am in bad spirits …”

He had good reason. Two days later, at a newspaper kiosk in Archangel, he bought a copy of Pravda. He saw a headline “Muddle Instead of Music.” It was a review of Lady Macbeth, and it dripped with malice. The music, said the review, “quacks, explodes, pants and sighs …” It was “fidgety, screaming, neurotic … a grotesquery suited to the perverted tastes of the bourgeois.”

Shostakovich was in his prime, only 30, “slender, yet supple and strong,” his career already brilliant with a string of successes—three symphonies, a brace of ballets, a piano concerto, scherzos, preludes, film scores. He had married, and had an affair, while he was writing Lady Macbeth, and the opera was alive with sexuality.

It had triumphed since its twin premieres in Leningrad and Moscow in 1934. It had opened in Buenos Aires, Copenhagen, Stockholm, Prague, London. Its lustful plot—the New York Sun called it “pornophony”—made it a sensation in Cleveland and at the Met in New York. By the end of 1935, it had raced through 94 performances in Moscow, where it was playing in two separate productions, and more than 80 in Leningrad. It was still selling out.

Then Stalin came. Shostakovich was briefly in Moscow, and he was summoned to the theater. “Lyova, you know I have a funny feeling about this invitation,” he told Levon Atovmyan, a close friend and fellow composer. He mistrusted the “shish-kebab temperament” of the conductor, the Armenian Alexander Melik-Pashayev. Stalin was in an ugly mood. His box was close to the brass and percussion. Their loudness further irritated him. He left.

Stalin may not have written the Pravda piece himself—it was unsigned—but without question he had approved it. It was followed ten days later by a savage attack on Shostakovich’s ballet, The Limpid Stream, set on a collective farm at harvest time. The composer was a “slick and high-handed fraud,” it said, who saw Soviet farmers as “sugary peasants” from a pre-revolutionary chocolate box. He was accused of “formalism,” a catch-all accusation that, like “Trotskyite,” had the ring of execution about it.

In the event, in the long cat and mouse game that Stalin played with him, the cat did not pounce. Shostakovich escaped, if barely, with his life. But he was never to write another opera, or ballet. He became “frail, fragile, withdrawn.” His arrest seemed so imminent, and for so long a time, that like many Russians he kept with him a small case with the essentials he would need in prison—a change of underwear, a little food, a toothbrush.

Before long, though, the cat did pounce on friends, and family, and colleagues. They were swallowed up in the Great Terror that Stalin let loose across the Soviet Union, and in particular on Leningrad, Shostakovich’s home town.

Many of his fellow musicians denounced him at meetings. Informers kept the NKVD secret police abreast of what those who defended him said in private conversation. Isaac Babel, master of the short story, scoffed at Pravda: “No one takes this seriously. The People keeps silent, and, in its soul, quietly chuckles.” The writer A. Lezhnev said, “I view the incident with Shostakovich as the advent of the same ‘order’ that burns books in Germany.” Vsevolod Meyerhold, the great theater director, spoke of the effect the “angry, cruel headlines” had on his friend. “He is now in very bad shape ….”

Lezhnev would be the first of the three to be tortured and shot. For good measure, Meyerhold’s wife, the actress Zinaida Raikh, was stabbed to death in the eyes in their apartment in Moscow, where Shostakovich had often stayed. The apartment was given to the chauffeur of Lavrenti Beria, the head of the NKVD.

Mikhail Tukhachevsky, a brilliant military innovator and a Marshal of the Soviet Union, was another good friend. He wrote to Stalin to defend Shostakovich. He, too, was to be tortured and shot, and his body dumped in a landfill. The librettist of The Limpid Stream, Adrian Piotrovsky, the dramatist who suggested Romeo and Juliet as a subject to Prokofiev, was arrested and shot.

A former lover of Shostakovich, the writer Galina Serebryakova, disappeared into the Gulag camps. The composer’s brother-in-law, a brilliant physicist known for his research into liquid crystals; his sister Mariya; his mother-in-law; his uncle—all were arrested. So many were arrested in Leningrad, the poet Anna Akhmatova said, that the city “dangled like an appendage from its prisons….”

Shostakovich’s great rehabilitation, for himself and for his city, now under siege by the invading Nazis, came in 1942 with his Seventh Symphony, “the Leningrad.” Its New York premiere in July that year was a stunning Soviet propaganda success. By the end of 1942, more than a dozen American orchestras had tackled it. “It is almost unpatriotic not to like Dmitri Shostakovich’s Seventh,” Life magazine noted, “This work has become a symbol of Russia’s heroic resistance.”

From Hitler’s Europe, “wherever the Nazis have mopped up,” the poet Carl Sandburg enthused [in the Washington Post], “no new symphonies.” But from Stalin’s Russia came the song “of a great singing people beyond defeat or conquest” who were making their contribution “to the meanings of human freedom …”

Lady Macbeth herself, of course, was not available to comment on the startling linkage of freedom with the Soviet Union, by way of Shostakovich.

She had, as it were, become a non-opera, much like a non-person. Her story, and that of her composer, so unlike those of any other opera, have a drama of all their own. There are ghosts that may flutter above the stage at the Met.

Brian Moynahan is the author of Leningrad: Siege and Symphony, a history of the World War II siege of Leningrad viewed through the lens of Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony.