Just a few months after the end of the Korean War, a bright, well-dressed young man named Kenneth Rowe matriculated at the University of Delaware to study engineering. Although only a little older than most of his classmates (he was 22 at the time), the man whose birth name was No Kum Sok had already lived though enough hardship and misadventure for an entire lifetime. On September 21, 1953, just days after an uneasy armistice had been signed to end hostilities between belligerents (despite not actually ending the war that officially is still extant), he had piloted his MiG-15 fighter plane across the 38th parallel, defecting from North Korea and landing unannounced at an American airbase. He had no idea about the $100,000 that the U.S. government had promised to any defector who would deliver a working MiG.

For No, it was the culmination of a lifetime of yearning for freedom in America. For the young Stalinist tyrant Kim Il Sung, who had nearly led his nation to ruin and was just now beginning to establish the most oppressive, hermetic regime on Earth, it was a call to further tighten his grip over his people.

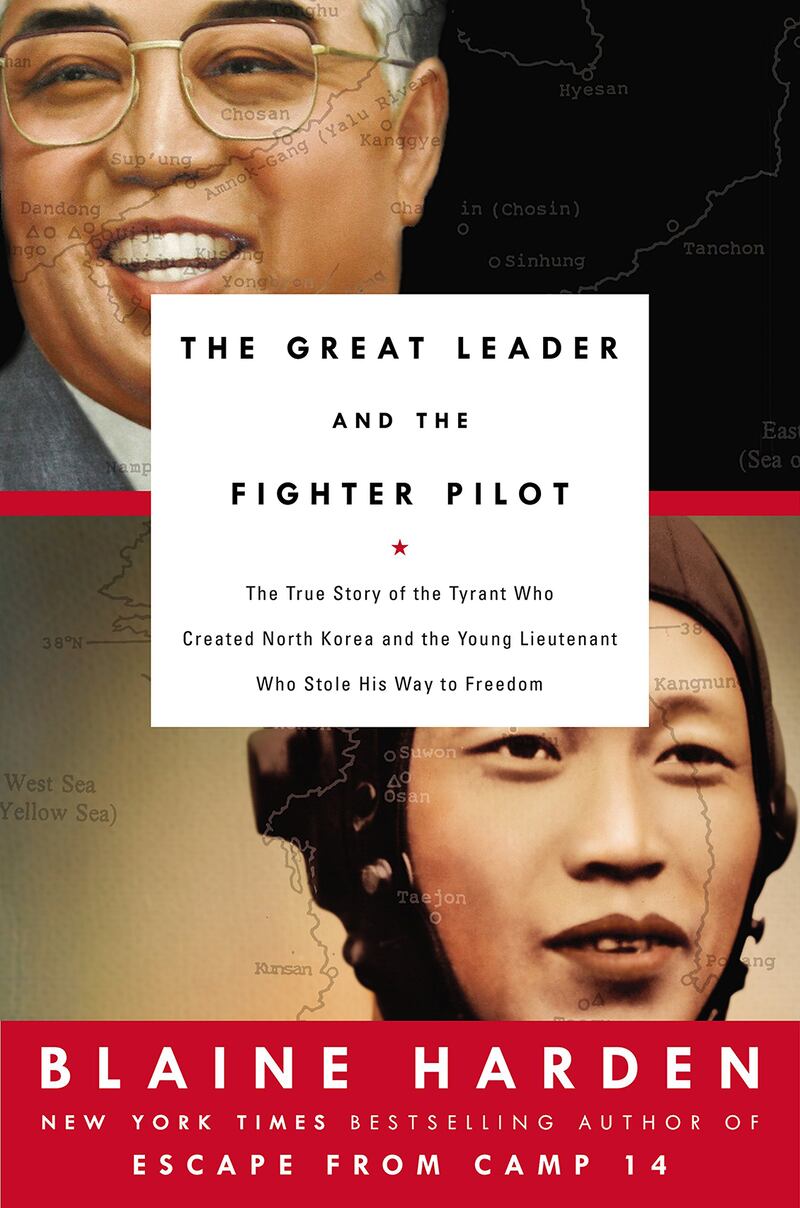

In The Great Leader and The Fighter Pilot, former Washington Post bureau chief Blaine Harden intertwines the stories of No and Kim to present an eminently readable picture of our most under-remembered war. Although No and Kim were never introduced and met only momentarily (during which encounter the young secret anti-communist briefly considered dispatching the Dear Leader with his service pistol), the combination of their biographies provide a view of the war from both angles—king and pawn, despot and vassal, fervent ideologue and counter-revolutionary.

We see here that Kim’s rise to power was exceedingly unlikely, given his ineptitude as a guerilla leader during World War II and later as a bumbling statesman, kowtowing to the will of Stalin and, to a lesser extent, Mao. Rather, he was lucky to be the right puppet at the right time for the larger communist powers, “a thug with a cause,” with just enough Machiavellian talent for disposing of his rivals. We watch him beg his masters to invade the South, largely botch the operation, and then go begging for help from China on the ground and Russia in the air.

After the war, he was able to put to good use the best gift ever given to him by the West. Ruthless carpet-bombing by America had caused such thorough devastation and misery among the people (the bombers eventually developed a “critical lack of targets”) that Kim was able to harness hatred of America and fear of their renewal of aggression (entirely rewriting history with regard to who had started the war) and use it to solidify his power. He was also able to demand funds from the Communist coffers to finance the rebuilding efforts. Harden writes: “By burning down cities, blowing up irrigation dams, and laying waste to the capacity of North Koreans to feed, clothe, and shelter themselves, the United States made Kim and his government seem pitiable and deserving—at least as seen from Moscow, Beijing, and other Communist capitals.”

Once Kim’s Stalinist fantasyland was firmly established, the rules of reality could be entirely suspended. As the purges of his enemies began in earnest, the scripts of the show trials are entirely farcical. As one political enemy “confessed” to an absurd spying charge: “Whatever punishment I am given by the trial, I will accept with gratitude. Had I two lives, to take them both would have been too little.”

Meanwhile, No, the son of a successful businessman, somehow went through an entire childhood un-indoctrinated, convinced that his country was being led astray. “He was so set on escaping,” Harden writes, “that he began to dream about it nearly every night. [In one dream], he stood on a sidewalk in New York City gazing up at the Empire State Building, the top of which was enveloped in clouds.”

When it looked as if war would be inevitable, he maneuvered to have himself sent to pilot school, his thinking being that the north would be swiftly defeated long before he would finish with his training. He was quite wrong—the war raged for years, and he eventually was given a MiG-15 (cutting-edge Soviet technology that could battle the American Sabre to a draw in the hands of a capable pilot) and sent to the front, where, like most North Korean pilots, he avoided combat after witnessing American air superiority. (Soviet pilots fared better, given their more rigorous training and experience.)

In addition to surviving American guns in the air, he avoided re-education by spouting the proper revolutionary bromides back at the base, the perfect communist in everything but his heart.

The full history of the war is told here in broader strokes than would be found in a more properly academic text, but Harden pays particularly evocative attention to the air war that took place in “MiG Alley,” after the ground war that had swept back and forth over the peninsula ground to a World War I-like stalemate in the long final stages.

Today, there remains a Kim on the throne of the Hermit Kingdom, and his Stalinist ideology and farcical cult of personality are no less extreme than his grandfather’s. We would do well to remember our country’s role both in the obliteration of the first Kim’s desires of tyrannical unification, and also the massive propaganda victory we gave him to help make his argument.