“My dad was a Purple Heart at 19 years old. In Korea, he got shot and he survived,” Michael Kirby said, choking back tears. “The Korean War didn’t kill him, but the government did.”

For just over a year in the late 1950s, Kirby, now a 64-year-old Colorado-based stockbroker, lived on the Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune in North Carolina with his parents, Sgt. Gerald “Red” Francis Kirby and Shirley Kirby, along with his four siblings.

It was there that the Kirbys were exposed to drinking water that the U.S. government now acknowledges as having contained dangerous chemicals—in some areas, hundreds of times the level allowed under safety regulations would allow—that may have caused serious medical conditions in military members and their families.

“My father was diagnosed with cancer at 27 years old... I was a little under 3 months old when we got to [Camp Lejeune] and we were supposed to be there for four years, but they sent my dad back because he was diagnosed with cancer,” Kirby recalled to The Daily Beast. “They gave him six months to live and we came back to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and he went to the VA hospital in Albany and he died at 28-and-a-half years old in January of 1960.”

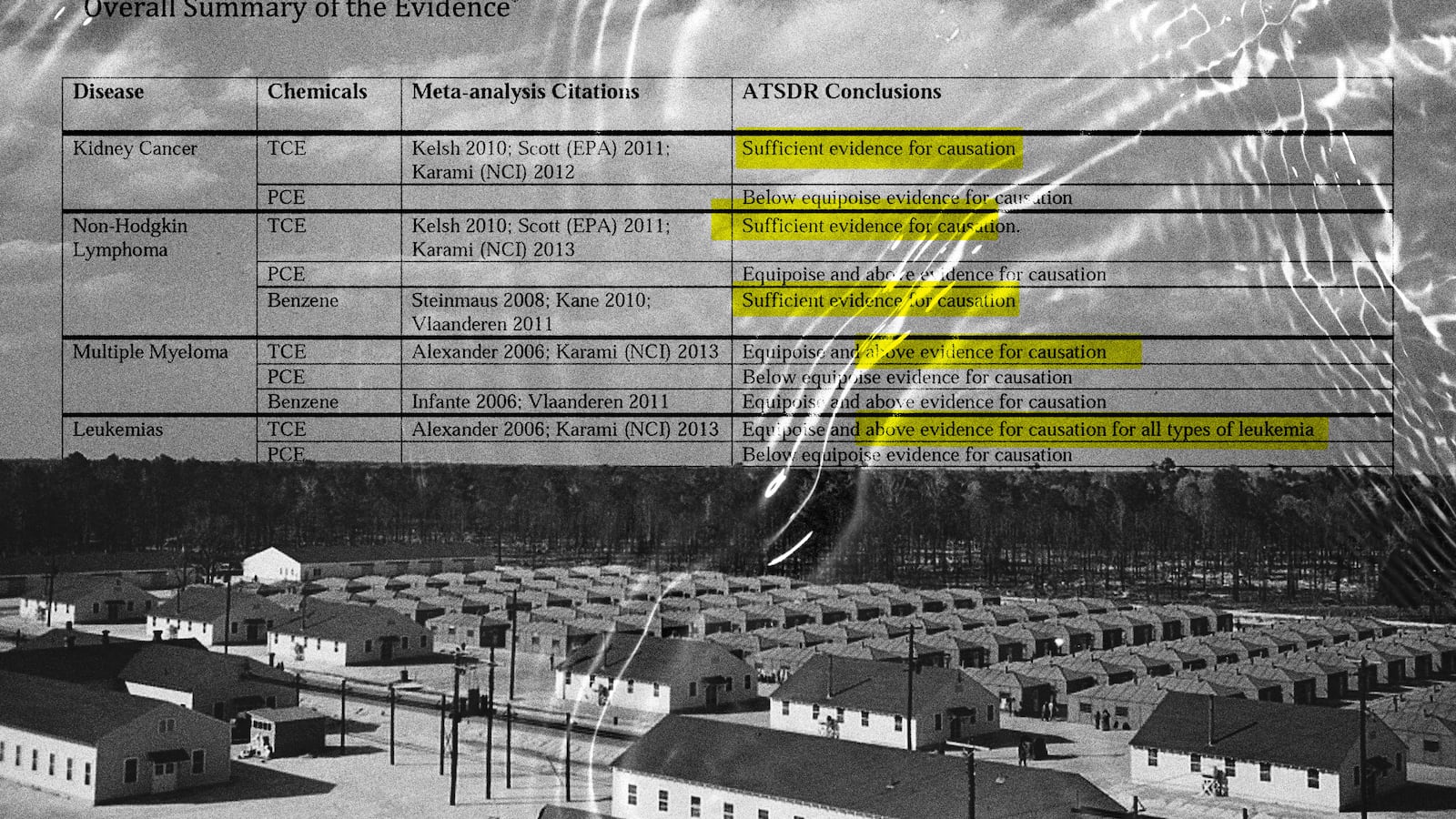

More than 60 years later, the grief-stricken son continued: “My dad died of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which you are 48 times more likely to get at Camp Lejeune, and the next-highest one was leukemia, that’s what my mother Shirley died from. She was diagnosed at 57, she died at 59 years old in 1994.”

At only 38 years old, after having endured the loss of both parents to the lethal disease, Kirby was himself diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 1996. The father of three recalled undergoing 15 rounds of chemotherapy and multiple surgeries, including stem-cell transplants. “I spent about six years of my life fighting cancer,” he explained.

And then, in 2017, Kirby’s brother Jerry was also diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma—the same disease that had afflicted him and killed their father.

“We never had any cancer in our family history until Camp Lejeune,” Kirby said.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that between 1953 and 1987, nearly a million veterans and civilians were potentially exposed to the contaminated water. Several years ago, the Department of Veterans Affairs declared there to be a “strong association” between that exposure and at least eight medical conditions, and allowed vets who were exposed to the drinking waters at Camp Lejeune to begin filing claims for disability benefits.

Many veterans have described the VA system as being “broken,” however, and as CBS News found earlier this year, a shockingly low level of Camp Lejeune-related claims have been approved. The VA has used “subject matter experts” to review claims but, according to the CBS investigation, “some of those doctors lacked expertise in relevant medical fields.”

Further attempts to seek justice for the Camp Lejeune exposures have been inhibited by North Carolina’s “statute of repose,” which dictates that judicial claims against a polluter—in this case Camp Lejeune—must be made within ten years within the polluting activity. The rule has gotten many cancer-related claims against the government dismissed, even though the associated diseases may take years, or in some cases decades, to show up in an exposed person.

And so earlier this year the Camp Lejeune Justice Act of 2022 was introduced, specifically seeking to waive that statute and allow individuals exposed to the toxic waters at Camp Lejeune between Aug. 1, 1953 and Dec. 31, 1987 to file lawsuits and potentially recover damages. The bill passed the House in March, mostly across party lines, and is currently awaiting a vote in the Senate as part of the Honoring Our PACT Act, a broader bill for veterans exposed to toxic chemicals.

Rep. Matt Cartwright (D-PA), who sponsored)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://cartwright.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=392082__;!!LsXw!U4gr06SUqBjyQ4p40yRcvTklXZNCRkrpNHk-jYP0W5UKaHWn-tcxbcmOoMlUWbCLYaQUCwvy28PxBOnvFgUoe0M7JH9E$">sponsored the House bill, told The Daily Beast that the Camp Lejeune situation is “tailor-made for people to get their day in court.”

He continued: “We are talking about contaminated water that led to people getting all sorts of horrible illnesses, including many forms of cancer. It’s fairness.”

The lawyer-turned-legislator lamented the existing legal statutes that have slowed any justice for “thousands and thousands of men, women, and children who were exposed to toxins at levels as high as 400 times the maximum safe level, things like benzene, known carcinogens, and at least eight different kinds of cancers.”

However, “It didn’t stop there. There were birth defects,” he added. “Remember: There weren’t just Marines there, there were Marine families and employees at Camp Lejeune—including women.”

Audrey Williams Pride and her husband, the late William James Morris II, a Navy Hospital Corpsman, moved to Camp Lejeune in 1984. After two years at the base, Pride became pregnant with her first child, a boy.

“I had just gone to the doctor. He said everything looked good, the baby looked good, you look good,” she recalled of an April 1986 visit. “That night, the baby was rumbling all over and my due date was close. I was full term. And then [the next] morning, I took my shower and I had an ink spot of blood.” Doctors were unable to hear anything on a sonogram, Pride recounted, and she was admitted for testing and eventually gave birth. Following the delivery, “my doctor sent his partner and told me the baby had passed. The baby died. The baby came out stillborn.”

Pride recounted how medical professionals were unable to explain how the baby they’d just determined to be healthy was delivered stillborn. “The doctor said, ‘I don't understand what’s going on. I’ve seen people shoot heroine in their feet before they even have their baby and [still] have a baby.’ He said, ‘I don’t know what to tell you. This baby was active. He was doing good. I have no words.’” Pride and her husband named their late son William James Morris III.

After the devastating loss, Pride said she fell into a deep depression, consumed by the mystery of what happened to her supposedly healthy baby. The results of an autopsy performed on the stillborn child, provided to The Daily Beast, were inconclusive.

Years later, however, Pride saw President Barack Obama talking about water contamination at Camp Lejeune. And the connection became immediately apparent to her.

An oft-cited CDC study from 2013 did, indeed, link exposures to the contaminants at Camp Lejeune to an increased risk of serious birth defects. And Dr. Hugh S. Taylor, the chief of obstetrics and gynecology at Yale Medicine further explained to The Daily Beast: “It seems that the water supply was contaminated with TCE, PCE and Benzene. In addition to cancers in adults, these agents can affect the fetus. PCE in particular has been associated with stillbirth. They can all cause low birth weight, placental problems, and birth defects. We still know very little about the long-term consequences to people born after an exposure as a fetus. There is good data to suggest that stillbirth is increased based on the amount of exposure.”

“I stopped in my tracks and I started my research. Before I heard that, I was in the bottom of a pit. I was suicidal. I thought it was something I did,” Pride said. But unlike military personnel, who are allowed to file for disability claims with the VA, Pride’s only form of justice can come via the courts. She filed a still-pending civil lawsuit)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://casetext.com/case/pride-v-us-dept-of-the-navy__;!!LsXw!U4gr06SUqBjyQ4p40yRcvTklXZNCRkrpNHk-jYP0W5UKaHWn-tcxbcmOoMlUWbCLYaQUCwvy28PxBOnvFgUoe_E_sV6R$">civil lawsuit against the U.S. Department of the Navy and has become an outspoken supporter of the Camp Lejeune Justice Act.

“I just want some type of justice,” she told The Daily Beast. “I’m 60 years old. Will the government ever say ‘I’m sorry’? Will I live to hear ‘I’m sorry’?”

Given the deeply divided nature of the Senate in 2022, Kirby admitted he’s slightly skeptical that the Honoring Our PACT Act will be passed in a timely manner. “Both parties want credit after 69 years of cover-up,” he said, fretting that the legislation could become a partisan football of sorts.

Nevertheless, he said, the legislation is “a long time coming.” The U.S. government, Kirby added, needs “to be accountable for what was wrong” and so legislators should “Do the right thing.” He concluded: “This should not be a partisan bill. This is for everybody. Military members are not Democrats or Republicans. They’re Americans.”

Rep. Cartwright agreed, noting that the ability to seek damages from the government would have far-reaching consequences for many military members—dead or alive—and their families affected by the contamination.

“What we have is people drinking this water in the mess halls, bathing in it, showering in it in their homes, and Marines out on exercise filling up their canteens from water buffalos full of this water for a couple of generations,” he said.

“This is where Marines go to do combat training,” Cartwright added of Camp Lejeune. Marines knowingly risk their lives when they enlist, he added. “They know they’re going to be in harm’s way, but what they didn’t expect is that the enemy was at home in the drinking water.”