Given the history of nuclear proliferation throughout the 20th century, it seems like a miracle that only two atomic bombs were ever deployed against the human population. And, it turns out, it really was a very lucky break.

There is one part of atomic history that hasn’t made the history books. Throughout the Cold War, the U.S. dropped several atomic bombs on unsuspecting people below, bombs that were multiple times more powerful than those dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II. Rather than being acts of extreme aggression, these “broken arrows” as they became known, were pure accidents, explosive “oopsies” committed by the U.S. military against mostly U.S. citizens. In what has been hailed as either luck or very proficient engineering of safety devices, none of the nuclear components on the falling bombs actually detonated.

It’s a near miss that one family in South Carolina was intimately familiar with. On the afternoon of Tuesday, March 11, 1958, the Gregg family was going about their business—kids playing in the yard, parents puttering around the house—when a malfunction in a B-47 flying overhead caused the nuclear bomb on board to drop out of the cargo hold and onto their Mars Bluff backyard. Miraculously, the only lives lost that day were those of the family’s free roaming chickens.

“You can’t really describe it. The noise was incredible, and the dust was crazy”

The three young girls—Helen, 6, Francis, 9, and their cousin Ella Davies, 9—had been playing in their outdoor playhouse for most of the afternoon. A little after 4 p.m, they wandered about 200 feet away as they continued their games. Their mother was inside the house sewing, while her husband, Walter, was working in the garage with their 6-year-old son, Walter Jr.

Suddenly, all hell broke loose. Around 4:20 p.m., a loud boom sounded and the sides and roof of the garage were blown off. The family home was shifted off of its foundation, with holes opening in the exterior structure and the furniture inside reduced to rubble. The backyard garden—including the girls’ playhouse—had vanished. In its place was a massive crater over 50 feet wide and 30 feet deep. Dust and debris filled the air.

“You can’t really describe it. The noise was incredible, and the dust was crazy,” Walter Jr. told The Sun News in 2003. His father added, “You couldn’t see 10 feet in front of your face.”

As the confusion and the smoke began to clear, Walter set about tracking down the members of his family. Everyone was a little worse for wear, with cousin Ella suffering the most severe injury with a cut to her face that required 31 stitches, but they were all miraculously alive.

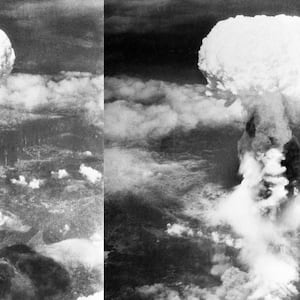

Two locals driving nearby heard the sound, saw a “large mushroom-shaped cloud” bloom over the Greggs’ property, and rushed to their neighbors’ aid. They loaded the Gregg family into their car and quickly drove them to the hospital. At that time, the Greggs still had no idea what had caused the sky to fall down around them.

In the meantime, the people who did know and who were no doubt in the middle of a massive panic attack, were the occupants of the B-47 now circling in that very same sky above, waiting for further instruction.

Mars Bluff was one of the earliest near misses on U.S. soil, but it was by no means the last. Today, it seems crazy no major action was taken to stop the flights that led to these Cold War accidents—or, at least, no major action that we know of. The public is still in the dark about much of this history. In 2018, nuclear weapons analyst Stephan Schwartz told WUNC that the Pentagon had come clean about 32 of these accidents, but that there was credible documentation that there were thousands more that they remain mum about.

The historical marker of the 1958 nuclear weapon loss incident in Mars Bluff, South Carolina.

DTMedia2 via Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0"If you go through some of the archival evidence publicly available, it seems like once a week or so, there was some kind of significant noteworthy accident that was being reported to the Department of Defense or the Atomic Energy Commission or members of Congress,” Schwartz said.

The justification for this massive risk to the American people was the bigger risk posed by the Soviet Union. In order to keep the country on ready alert for a nuclear attack, the military had nuclear-armed bombers constantly flying in the skies above. Two years after the Mars Bluff accident, they would launch Operation Chrome Dome, which mandated that multiple B-52’s armed with two nukes each would be in the air 24 hours a day.

While this program had not officially launched when the Greggs’ home was bombed, preparations were being made.

The B-47 in question that day was in the middle of a training exercise named “Operation Snow Flurry,” which required the specialized crew to load their plane with an atomic bomb, and fly from Savannah, Georgia to the U.K. on a practice run.

Almost from the beginning, things started to go wrong. The crew was being timed, so the pressure was on to perform at their absolute best. Needless to say, stress was running high, especially as the delays began before they had gotten even close to getting off the ground. The source of those delays: their deadly passenger, which was refusing to properly lock into its seat in the cargo bay. So, the crew did what anyone would do with a troublesome atomic weapon more destructive than those dropped on Japan on their hands…they MacGyvered it.

“When the loading team had trouble engaging the steel locking pin, they called the weapons release systems supervisor for assistance. He took the weight of the weapon off the plane’s bomb-shackle mechanism, put it onto a sling, and then ‘jiggled’ the pin with a hammer until it seated,” Clark Rumrill wrote in American Heritage in 2000.

The problem with this solution became apparent soon after takeoff. During takeoff, it was policy for the locking mechanism to be disengaged to allow the crew to quickly offload the bomb in case of an emergency. Once in the air, they were required to lock the bomb back into place for the safety of all involved.

But the bomb wouldn’t re-lock and a red light began to flash in the cockpit. The plane’s 29-year-old navigator, Bruce Kulka, was sent to the cargo hold to manually adjust the locking pin. According to Rumrill, this required the entire plane to be depressurized, all of the airmen to go on oxygen, and for Kulka to ditch his parachute, as the passage to the cargo bay was too skinny for the extra bulk.

That was just the tip of the iceberg of the issues with this fix-it attempt. More critical was the fact that Kulka didn’t actually know where the locking pin was located. He was sent in to deal with a nuclear weapon blind, so to speak. What happened next was like something out of a very dark comedy.

“A short man, he jumped to pull himself up to get a look at where he thought the locking pin should be,” Rumrill wrote. “Unfortunately, he evidently chose the emergency bomb-release mechanism for his handhold. The weapon dropped from its shackle and rested momentarily on the closed bomb-bay doors with Captain Kulka splayed across it in the manner of Slim Pickens in Dr. Strangelove.

“Kulka grabbed at a bag that had providentially been stored in the bomb bay, while the more-than-three-ton bomb broke open the bomb-bay doors and fell earthward. The bag Kulka was holding came loose, and he found himself sliding after the bomb without his parachute. He managed to grab something—he wasn’t sure what—and haul himself to safety.”

The bomb fell 20,000 feet below and landed almost exactly on the Gregg daughters’ playhouse. While the nuclear bomb didn’t detonate—it is believed that the core of the bomb was transported separately at the time, though it has never been 100-percent clear if that was the case—the TNT contained in the bomb in order to trigger an atomic blast did.

A Mark 6 nuclear bomb at the National Museum of the United States Air Force.

Public DomainWithin two hours of the bomb falling, the entire force of the military had descended on the 50-person town of Mars Bluff to do damage control. They announced that no radiation had been discovered in the area and commenced a military clean up.

Amazingly, there was no real fallout from this early Cold War accident, at least in the U.S. Americans understood the great risks being taken in the name of protecting the home front, and they seemed to be OK with them. The story received bigger and more critical play in places like Canada and the U.K., countries that were American allies and thus were also subject to armed U.S. bombers flying overhead.

Walter Gregg, for his part, was shockingly good natured about the incident. After being promised compensation by the government for his destroyed home and property, he joked, “I’ve always wanted a swimming pool, and now I’ve got a hole for one at no cost.”