Criminality is the child’s fault, something he has done deliberately and with choice. It is also the parents’ fault, something they could have prevented with decent moral education and adequate vigilance. These, at least, are the popular conceptions, and so parents of criminals live in a territory of anger and guilt, struggling to forgive both their children and themselves. To be or to produce a schizophrenic or a child with Down syndrome is generally deemed a misfortune; to be or produce a criminal is often deemed a failure. While parents of children with disabilities receive state funding, parents of criminals are frequently prosecuted.

If you have a child who is a dwarf, you are not dwarfed yourself, and if your child is deaf, it does not impair your own hearing; but a child who is morally culpable seems like an indictment of mother and father. Parents whose kids do well take credit for it, and the obverse of their self-congratulation is that parents whose kids do badly must have erred. Unfortunately, virtuous parenting is no warranty against corrupt children. Yet these parents find themselves morally diminished, and the force of blame impedes their ability to help—sometimes even to love—their felonious progeny.

Having a child with physical or mental disabilities is usually a social experience, and you are embraced by other families facing the same challenges. Having a child who goes to prison frequently imposes isolation. Parents on visiting day at a juvenile facility may complain to one another in a friendly way, but aside from those communities in which illegality is the norm, this is a misery that doesn’t love company. The parents of criminals have access to few resources. No colorful guides posit an upside to having a child who has broken the law; no charming version of “Welcome to Holland” has been adapted for this population. This deficit also has advantages: no one trivializes what you are going through; no one uses learning centers with colorful crepe-paper decorations to try to turn your grief into a festivity. No one proselytizes that the only loving response to your child’s crime is gladness or urges you to celebrate what you want to mourn.

For most horizontal identities, the issue of collective innocence is central; the heart-tugging argument is that disabled children do not deserve to be castigated. Here, we deal with guilty children and, in some cases, with parents who have grossly erred. Yet many of these families have also been marginalized and brutalized, emotionally and economically isolated, depressed, and frustrated. I kept meeting parents who wanted to help their kids but didn’t have the knowledge or means to do so effectively; like the parents of disabled children, they couldn’t access the social services to which they were ostensibly entitled. Heaping opprobrium on these parents exacerbates a problem we could instead resolve. We deny the reality of their lives not only at the expense of our humanity but also at our personal peril.

Three risk factors wield overwhelming significance in the making of a criminal. The first is the single-parent family. More than half of all American children will spend some time as a member of a single-parent family. While 18 percent of American families fall below the poverty level, 43 percent of single-mother households do. Kids from single-parent homes are more likely to drop out of school, less likely to go to college, and more likely to abuse substances. They will work at lower-status jobs for lower pay. They tend to marry earlier and divorce earlier and are more likely to be single parents themselves. They are also much more likely to become criminals.

The second risk factor, often coincident with the first, is abuse or neglect, which affects more than three million American children each year. John Bowlby, the original theorist of attachment, described how abused and neglected children see the world as “comfortless and unpredictable, and they respond either by shrinking from it or doing battle with it”—through depression and self-pity, or through aggression and delinquency. These children commit nearly twice as many crimes as others.

The third giant risk factor, which often accompanies the first two, is exposure to violence. One study found that children in its sample who suffered physical maltreatment, witnessed interparental violence, and encountered violence within their community were more than twice as likely to become violent delinquents as those from peaceable homes; of course, abused children also may carry their parents’ genetic predisposition toward aggression. Taking them away from their families, however, seldom helps, because the child-welfare system is also associated with high rates of crime. Jess M. McDonald of the School of Social Work at the University of Illinois has flatly stated, “The child-welfare system is a feeder system for the juvenile justice system.”

Families of criminals often struggle both to admit that their child has done something destructive, and to continue to love him anyway. Some give up the love; some blind themselves to the bad behavior. The ideal of doing neither of those things borrows from the idea of loving the sinner while hating the sin, but sinners and sins cannot so easily be separated; if human beings love sinners, we love them with their sin. People who see and acknowledge the darkness in those they love, but whose love is only strengthened by that knowledge, achieve that truest love that is eagle-eyed even when the views are bleak. I met one family whose own tragedy had led them to embrace these contradictions more than any other, one mother whose love seemed both infinitely deep and infinitely knowing of a blighted person. Hers was a love as dark and true, as embracing and self-abnegating, as Cordelia’s.

On April 20, 1999, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, seniors at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colo., placed bombs in the cafeteria, set to go off during first lunch period at 11:17 a.m., and planned to shoot anyone who tried to escape. Errors in the construction of the detonators prevented the bombs from exploding, but Klebold and Harris nevertheless held the whole school hostage, killing 12 students and one teacher before turning their guns on themselves. At the time, it was the worst episode of school violence in history. The American right blamed the collapse of “family values,” while the left mounted assaults on violence in the movies and sought to tighten gun-control laws. Wholesale critiques of the larger culture were offered as explanation for these inexplicable events.

The number of people killed that day is generally listed as 13, and the Columbine Memorial commemorates only 13 deaths, as though Klebold and Harris had not also died that day in that place. Contrary to wide speculation then and since, the boys did not come from broken homes and did not have records of criminal violence. The wishful thought of a world that witnessed this horror was that good parenting could prevent children from developing into Eric Harris or Dylan Klebold, but malevolence does not always grow in a predictable or accountable manner. As the families of autistics or schizophrenics wonder what happened to the apparently healthy people they knew, other families grapple with children who have turned to horrifying acts and wonder what happened to the innocent children they thought they understood.

I set out to interview Tom and Sue Klebold with the expectation that meeting them would help to illuminate their son’s actions. The better I came to know the Klebolds, the more deeply mystified I became. Sue Klebold’s kindness (before Dylan’s death, she worked with people with disabilities) would be the answered prayer of many a neglected or abused child, and Tom’s bullish enthusiasm would lift anyone’s tired spirits. Among the many families I’ve met in writing this book, the Klebolds are among those I would be most game to join. Trapped in their own private Oresteia, they learned astonishing forgiveness and empathy. They are victims of the terrifying, profound unknowability of even the most intimate human relationship. It is easier to love a good person than a bad one, but it may be more difficult to lose a bad person you love than a good one.

“I can never decide whether it’s worse to think your child was hardwired to be like this and that you couldn’t have done anything, or to think he was a good person and something set this off in him,” Sue said. “What I’ve learned from being an outcast since the tragedy has given me insight into what it must have felt like for my son to be marginalized. He created a version of his reality for us: to be pariahs, unpopular, with no means to defend ourselves against those who hate us.” Their attorney filtered their piles of mail so they would not see the worst of it. “I could read three hundred letters where people were saying, ‘I admire you,’ ‘I’m praying for you,’ and I’d read one hate letter and be destroyed,” Sue said. “When people devalue you, it far outweighs all the love.”

An event of such enormity completely disrupts one’s sense of reality. “I used to think I could understand people, relate, and read them pretty well,” Sue said. “After this, I realized I don’t have a clue what another human being is thinking. We read our children fairy tales and teach them that there are good guys and bad guys. I would never do that now. I would say that every one of us has the capacity to be good and the capacity to make poor choices. If you love someone, you have to love both the good and the bad in them.” Sue worked in a building that also housed a parole office and had felt alienated and frightened getting on the elevator with ex-convicts. After Columbine, she saw them differently. “I felt that they were just like my son. That they were just people who, for some reason, had made an awful choice and were thrown into a terrible, despairing situation. When I hear about terrorists in the news, I think, ‘That’s somebody’s kid.’ Columbine made me feel more connected to mankind than anything else possibly could have.”

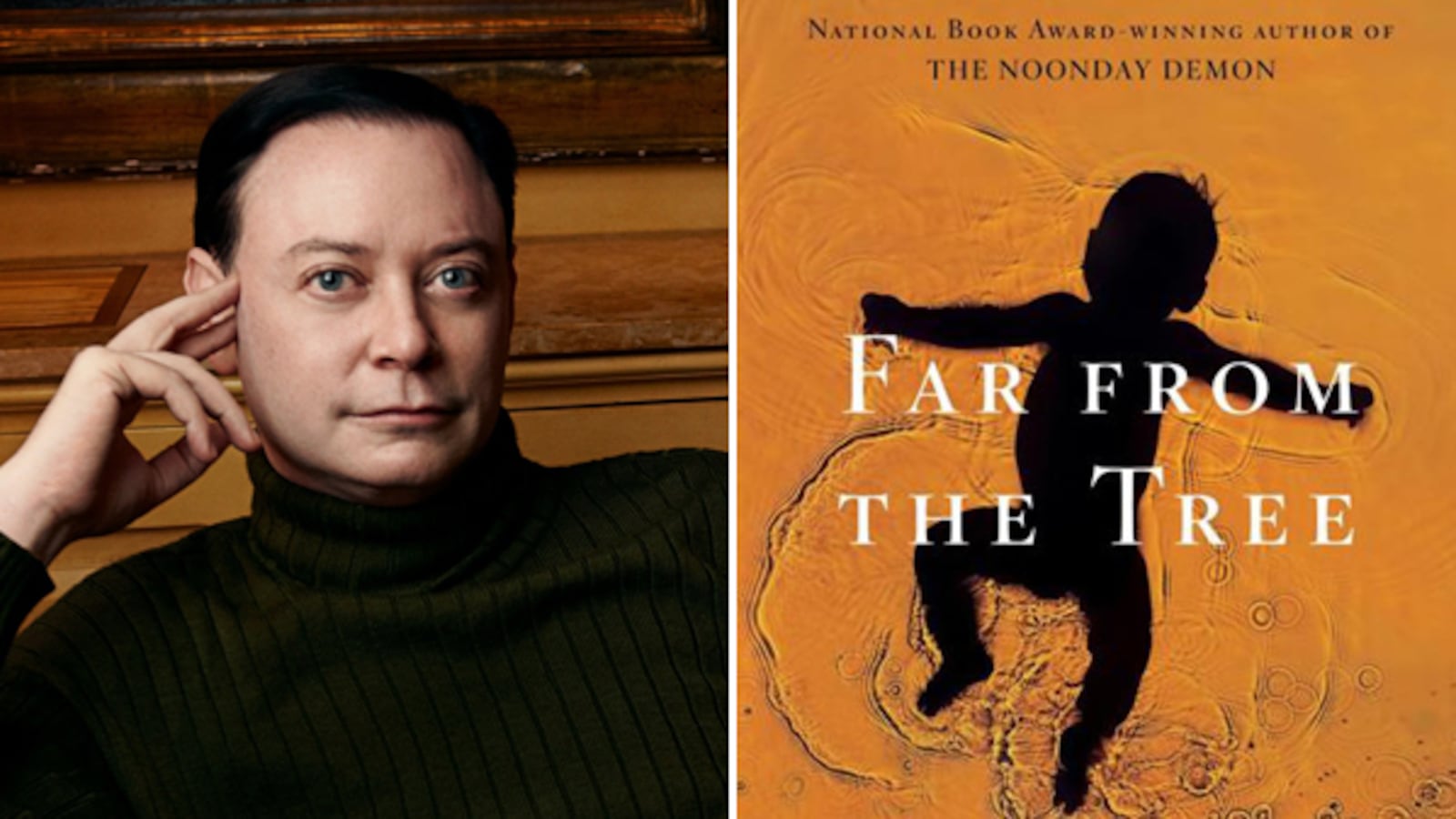

Excerpted from FAR FROM THE TREE: Parents, Children, and the Search for Identity. Copyright © 2012 by Andrew Solomon. Excerpted with permission by Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.