ROME–Caravaggio is perhaps best known in the art world for his dramatic command of light and dark–known as chiaroscuro–which gives realistic life to his masterpieces through the manipulation of sharp and subtle tones. But Caravaggio also had a little chiaroscuro in his personal life.

He was a deeply troubled soul with dangerously dark moods and only fleeting moments of levity. His masterpieces were almost all completed in a few short weeks, but they were inevitably followed by months of madness as the artist spiraled into an angry and violent depression that led to frequent fights and even murder, alleged to have been committed over a plate of artichokes served the wrong way.

Michelangelo Merisi was born in 1571 near Milan in a town called Caravaggio, from which his painting name derives. He came to Rome in his teens after being taken in by a local painter after losing his entire family to the bubonic plague when he was just 11. The late 16th century and into the 17th century marked the height of the Catholic Counter-Reformation when the church was as political as it was religious, building its intellectual influence through often corrupt means. It was a brilliant time to work for young painters like 20-year-old Caravaggio, who was still trying to come to grips with his immense talent and find a way to channel it into saleable art.

He studied under Giuseppe Cesari who was, for lack of a better description, a Vatican ceiling painter specializing in frescoes and a favorite of Pope Clement VIII. Though it is widely understood that Caravaggio never painted a fresco in his life, Cesari's influence is visible in some of his larger scale works which require stamina and concentration, You can also see the attention to detail in his fruit depictions, which was his designated task at Cesari's studio.

Caravaggio's time in Rome was troubled and relatively short, but he left his mark in the nearly 10 years he spent in Rome and there are still 25 masterpieces he created here to see today.

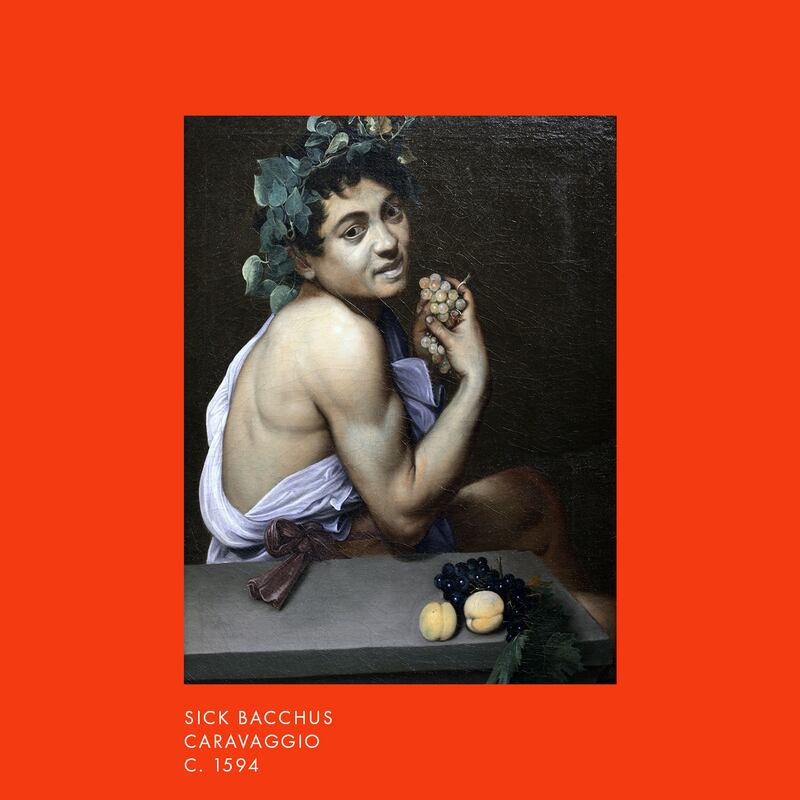

One of Caravaggio's most interesting masterpieces in Rome and a good place to start to understand the artist is his self-portrait as Sick Bacchus (1594). Bacchus was the Roman god of grapes and fertility and the deity equal to the Greek god Dionysus. The painting hangs in Room 8 of the Borghese Gallery in central Rome. You'll need to book online before you go because the gallery strictly limits the number of visitors inside at any one time and the wait can be weeks or even months to get a coveted slot. Note his jaundice skin and pasty lips that bring out the faded green of the late season grapes he is holding near his face. He is wearing a grape leaf crown on his head and his forced grimace is at once sorrowful and sarcastic. Two peaches on the table beside a spray of dark grapes have an erotic allure. This is classic Caravaggio, to turn a simple still life into something so provocative. And it is indicative of his earliest work, in which almost all of his still life paintings have a human element.

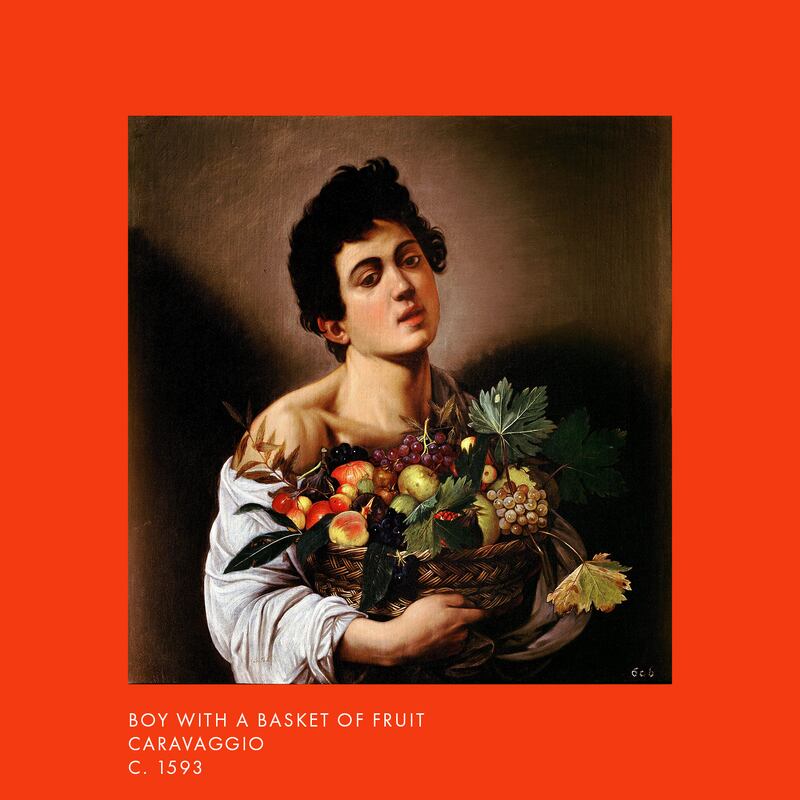

The Caravaggio collection at the Borghese Gallery is often on loan. The J. Paul Getty had many of the better pieces for much of 2017 and 2018, but they are safely back on the gallery walls. Boy With a Basket of Fruit (1593) is a gallery favorite but most critics aren't sure why because it is has never been considered to be one of his best works due to proportion and balance issues. Again, Caravaggio has made Bacchus in his own image, but a closer look will show that the figure in the painting is offering the glass of wine with his left hand, which has led art critics to surmise that Caravaggio, who was right-handed, was using a mirror as he painted. Unlike most masters of this era, Caravaggio did not use sketches, so everything on the final canvas is as it was channeled through the artist's skilled brush at the moment he created it.

(Caravaggio had a sense of humor between his bouts of madness, too. At the Uffizi in Florence, his 1597 oil painting of Bacchus features a tiny self-portrait seemingly swimming–or drowning–inside the carafe of red wine by his elbow. It was first discovered in 1922 by restorers and was brought to better light in 2009.)

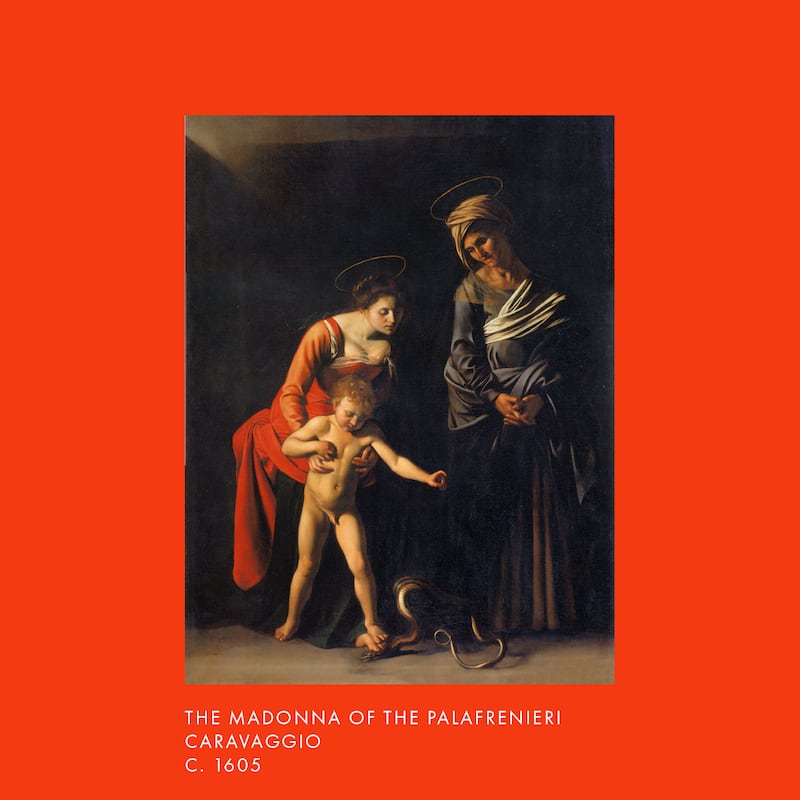

Among the other Caravaggio works to check out at the Borghese Gallery, two stand out, including The Madonna of the Palafrenieri (1605), which was rejected by its patron who had wanted it for a chapel but shunned it because of the portrayal of St. Ann, the Virgin's mother, as an old and wrinkled real woman. Mary’s mother had always been portrayed as a flawless woman. But Caravaggio thought she should be portrayed in a more human light, and the age she would have been the scene depicted played out. Caravaggio also used a well-known prostitute in Rome at the time to sit for the busty, sexualized Virgin Mary, who is depicted teaching the Christ child how to kill a serpent. The painting lay hidden away for nearly a century before it was brought out, but it never adorned the chapel it was meant for.

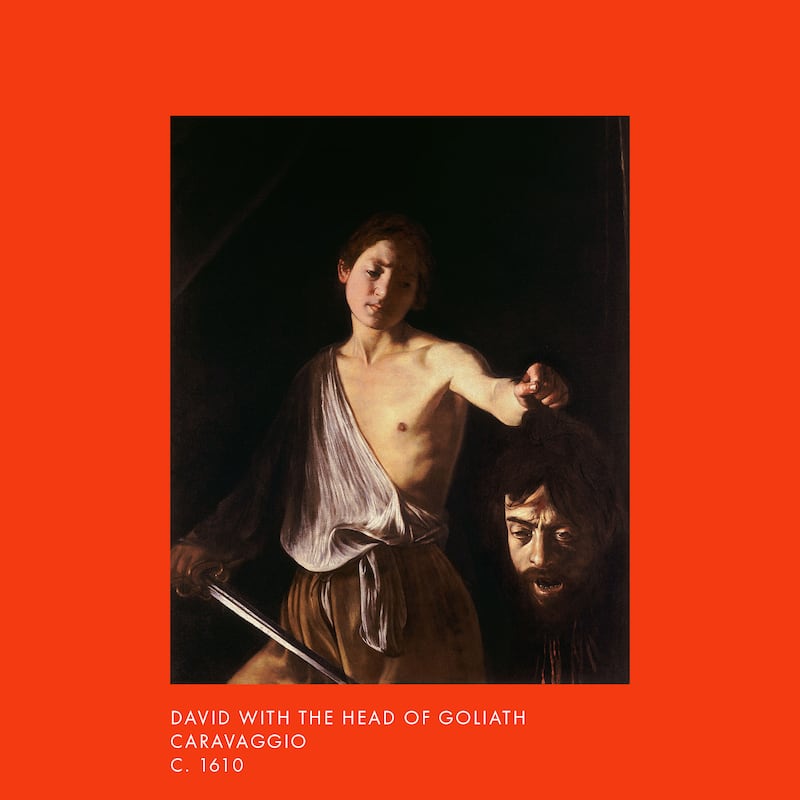

The David with the Head of Goliath (1610) is also here at the Borghese Gallery and it was one of his last paintings, created when he was in exile from Rome after committing murder. He spent his exile in Naples, Sicily and Malta where he left a number of works, but this one is a plea to return to the city he felt had launched his career. Caravaggio painted it as a sort of ancient selfie, using his own scruffy likeness on David's cut-off head. It was thought to be a plea for a pardon after he was banished from Rome for murder in 1610. He did receive the pardon but died of malaria, alone on a beach north of Rome, before he made it back to the city.

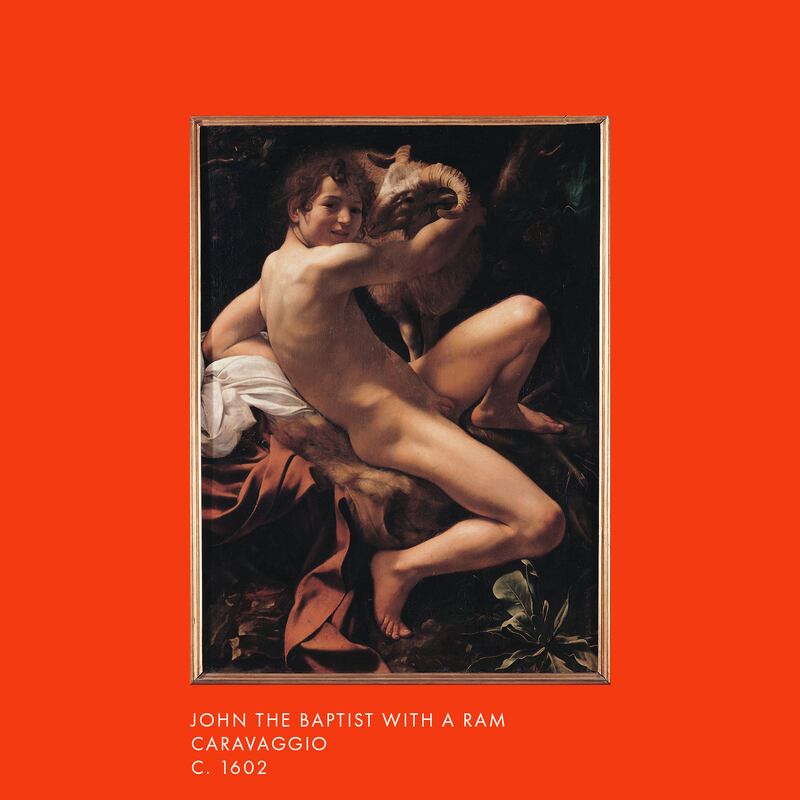

In the Hall of St. Petronilla of the Capitoline Museums overlooking the Roman Forum in the heart of what was ancient Rome, one can see Caravaggio as he developed his craft, moving beyond his own image as his primary model. One of his few known assistants was a pubescent boy known only as Cecco, who is also widely thought to have been one of his lovers. Cecco shows up in a number of his depictions of John the Baptist, including the overtly sexualized John the Baptist With a Ram (1602) found here. Things critics want you to note here are the wrinkled sheets on which the young boy reclines and the way he looks surprised as if he has been caught about to kiss the ram. Critics have long assumed the ram symbolizes Caravaggio's own lust for his young model. The only other Caravaggio in these expansive museum halls is The Fortune Teller (1595 and 1598), which hangs close by. It is a less interesting painting, though the male model is thought to be Mario Minniti, whom Caravaggio lived with in Rome and who is also often described as another of his lovers.

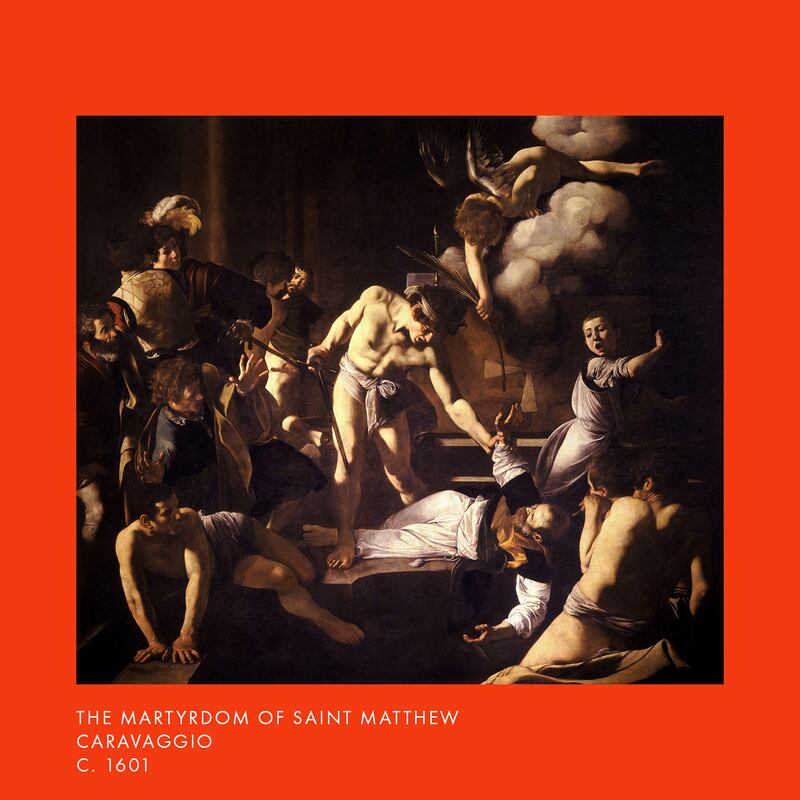

By the time he was 26, at the height of his time in Rome, Caravaggio had created 40 works of note which won him one of his most important commissions. Cardinal Francesco del Monte hired him, providing a salary plus room and board, to provide a trio of religious images depicting various phases of St. Matthew's life inside the Contarelli Chapel at the fully functional church of San Luigi dei Francesi near the Pantheon in Rome. Entrance is free, and the church is open to the public mornings and afternoons with the exception of when mass, weddings, and funerals are held.

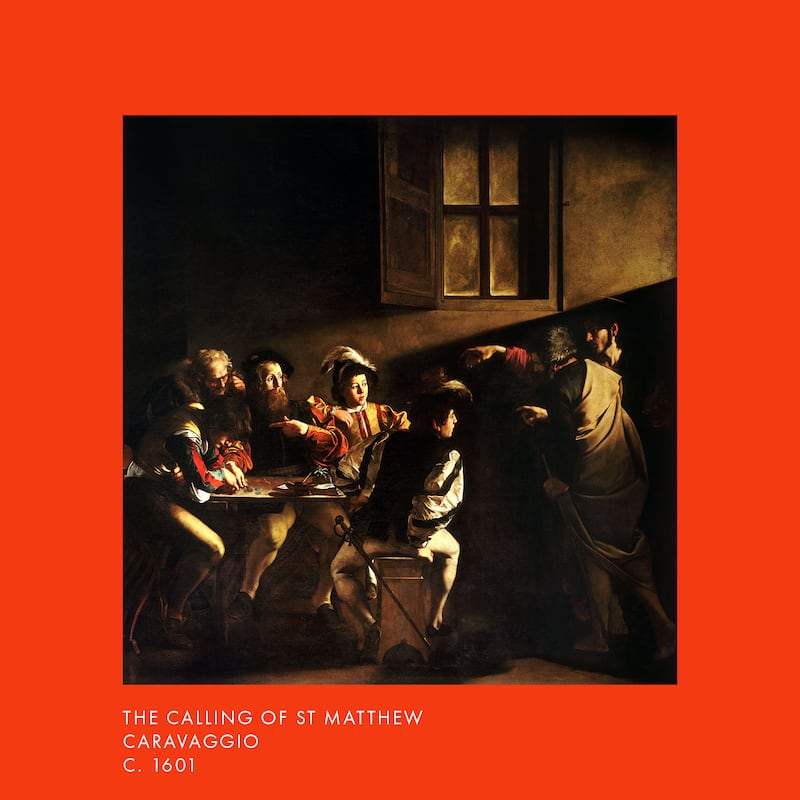

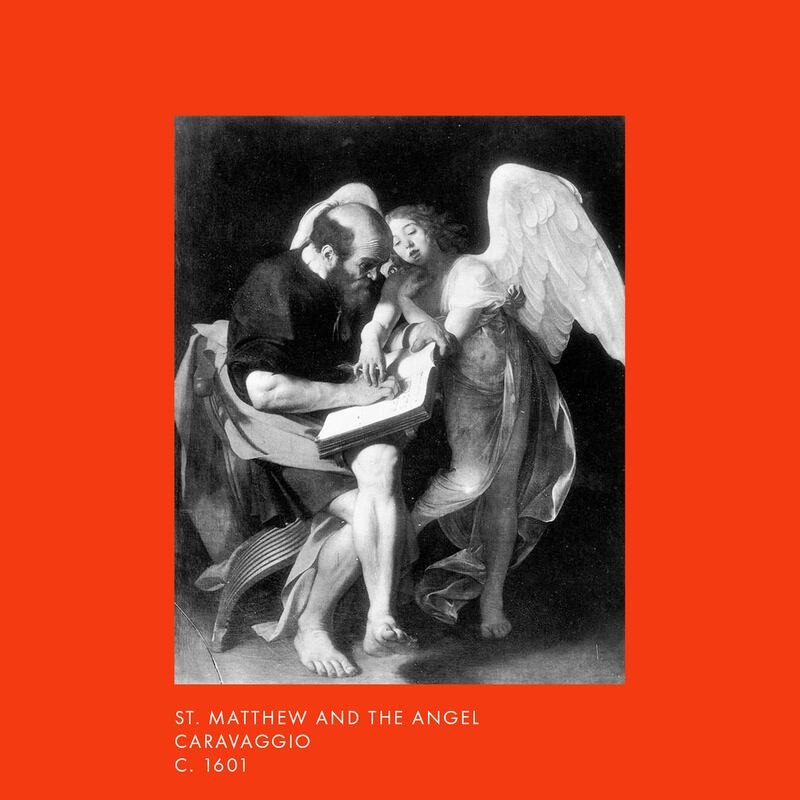

In the course of a few months, he created St. Matthew and the Angel, The Calling of St. Matthew, and The Martyrdom of St. Matthew (1601). Again, his work was far too avant garde for the era and the church and public scorned him for not sticking to the accepted practices in portraying religious scenes. The saints being painted at the time were angelic with perfect features. Caravaggio's saints were modern day street Romans with recognizable faces. The Calling of St. Matthew looks somewhat like a pub scene with men sitting around a table, caught in what had by then become Caravaggio's fantastical use of light as an angel appeared to beckon Matthew. The men at the table look aghast and Matthew's hand is placed in a very human "who me?" pose.

What most critics note about this painting is that the prominent window is not the one generating the light, which makes the light seem to be coming from somewhere otherworldly. The painting was created in situ meaning the light from the church's own windows above cast shadows to complement the work. The St. Matthew and the Angel hanging in the chapel is not the original painting designed for the space. In the first version, which the Del Monte rejected for lack of decorum, Caravaggio had depicted Matthew in all-too-human state, naked from the legs down with the angel essentially draped over and touching him as Caravaggio wrote. The second version, which is on display, has him clothed with the angel hovering overhead, not touching the man, but note the dirty feet, which is the compromise Caravaggio insisted on to keep it real.

Perhaps one of the most realistic of Caravaggio's works in Rome is Judith Beheading Holofernes (1599) which resides in the Palazzo Barberini. Note here Caravaggio's use of light to make the blood spurting from Holofernes's neck as the young Jewish widow from the Bible's Book of Judith slices his neck. The light on this act comes from the top left, which illuminates the blood, the knife and Judith's rather quizzical furrowed brow. This biblical scene has been depicted by countless artists, but none in such real time as Caravaggio's which somehow looks as if the sword is moving through the man's neck. In almost every other depiction, Judith's maid servant Abra is shown as the young woman she was. Caravaggio aged her into an old woman, presumably to show the effect of the horror she witnessed.

Rome has more than 900 churches within the confines of the city, and you'd be forgiven for only going into the most ornate and inviting. But a nondescript church on the back of Piazza del Popolo has two of the best Caravaggio originals you might ever hope to see and entrance is free, though a stern nun often give guilty looks to those who don't make donations in any of the many boxes. Santa Maria del Popolo is one of three churches on the popular square, but not one visitors automatically flock to. It's flat facade and uninviting doorway defy what's inside: two of the painter’s most stunning works with an original Raphael thrown in for good measure. The Caravaggio works flank a lesser artist’s work whose depiction of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary takes center stage. But step back and note how The Conversion of St. Paul (1601), also called The Conversion on the Way to Damascus, uses the natural light from the basilica’s high windows to accentuate his own chiaroscuro scene. The church has added lights that are turned on when the sun sets, but just the thought of Caravaggio studying the natural light to work with that he created on the canvas is really what viewing a masterpiece is all about. Across the tiny chapel is the Crucifixion of St. Peter (1601), painted the same year. Critics at the time hated it because it showed St. Peter still alive and looking rather upset that he had been nailed to the cross. He had requested to be crucified upside down to avoid competing with Jesus Christ. There is no blood from the wounds, which critics say was a special request by the patron. But St. Peter is clearly looking at an image that gives him comfort, thought to be instead looking at an image of Jesus' crucifixion. The scene shows the executioners’ faces well hidden. What most critics admire about this work is how Caravaggio was able to recreate the physics of lifting the cross, that he calculated the angle and the way St. Peter reacts to gravity as the cross is hoisted up. But for the casual admirer, it is the light—both natural from the windows above and manmade by Caravaggio’s hand—that is worth noting, and how St. Peter’s aged body is so perfectly defined within it. One of Caravaggio's many biographers, Andrew Graham-Dixon, who wrote Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane, believes Caravaggio's troubled temperament came from the traumatic loss of his family to the plague. Others believe he may have had syphilis or that the lead in the paints he used contributed to his demeanor.

“He almost seems bound to transgress,” Dixon writes. “It’s almost like he cannot avoid transgressing. As soon as he’s welcomed by authority, welcomed by the pope, welcomed by the Knights of Malta, he has to do something to screw it up. It’s almost like a fatal flaw.”

Caravaggio's remains were found on the beach in Tuscany in 1610, some four years after he had been banished from Rome, according to various accounts that do not agree on an exact date. Several notes and inscriptions refer to the remains as his, though it is unclear how that was known at the time—whether his remains were identifiable or if he had possessions on him that proved who he was. He was then buried and exhumed and buried again, with his final resting place in Porto Ercole's San Sebastiano cemetery sometime before 1956, when the last burials there occurred. He was exhumed a final time in 2010 when carbon dating and other genetic analysis confirmed his identity. Caravaggio had no known children and his parents died when he was young, but registries in his namesake town identified 20 people he could have been related to. Those bodies were also exhumed to perform DNA matches. Caravaggio is thought to have died from either malaria or an infected sword wound at the age of 38, and he was most certainly alone. No one will ever fully understand whether his madness fueled his genius or, more likely, the other way around.