True crime filmmaker Joe Berlinger--whose latest documentary, Whitey, premieres Friday in theaters and via video on demand--has a theory about why we’re so captivated by homicidal miscreants like James Joseph “Whitey” Bulger Jr., who terrorized Boston with murder and mayhem for the better part of four decades.

“I think there’s a dark side to everybody,” Berlinger says. “I think everybody wonders what it would be like to cross that line. Most people have a conscience. But the dark side makes everybody almost envious of somebody who breaks all the rules and gets away with it for a long time.”

Berlinger--who, when he’s not making movies, hosts The System, a weekly series on Al Jazeera that probes “the underbelly and dark corners” of criminal justice American-style--adds that Bulger, who is now 84 and, after 16 years on the lam, finally in prison, might still be getting away with it.

“It’s a particularly irresistible narrative that has been appealing to people because he truly got away with a life of crime and murder until he was arrested,” Berlinger says. “I think you can argue that he has gotten away with it. To be sentenced to two life terms plus five years is hardly punishment for an 83-year-old man. If you told me I could make it to 83, I might take that deal.”

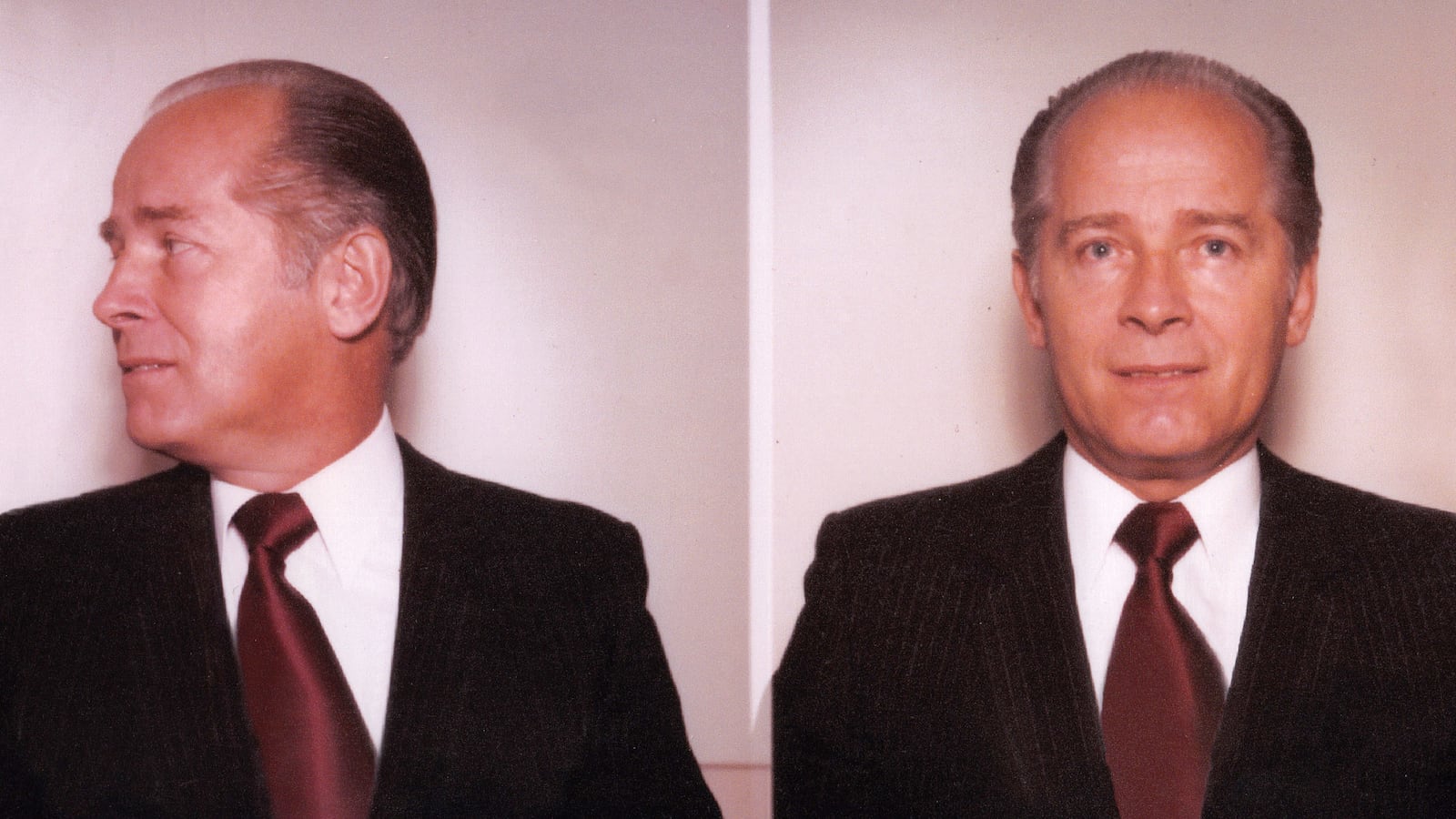

Like Dillinger and Bonnie & Clyde, Bulger enjoys perverse folk-hero status in the public imagination; his exploits have been the subject of a dozen books--authored by many of the law officers and at least one criminal, celebrity hit man Kevin Weeks, who sit for Berlinger’s camera--and have inspired a few Hollywood types to celebrate him on the big screen. Jack Nicholson’s maniacally malevolent Boston mob boss in Martin Scorcese’s The Departed was loosely based on Bulger; Ben Affleck and Matt Damon (who played a corrupt cop in The Departed) are reportedly planning a feature film explicitly portraying Whitey; and Johnny Depp is starring in Black Mass, a Bulger biopic scheduled for release next year.

Berlinger’s documentary--which is subtitled United States of America v. James J. Bulger--focuses on his trial last year in Boston federal court on 33 counts, including 19 for murder, and the role played by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the U.S. Department of Justice in enabling and protecting Bulger’s ghastly criminality.

Aside from the petty corruption of law enforcement authorities--in the form of Bulger’s bribes to dirty cops and FBI agents--Berlinger explores the larger, and in his view more damaging, institutional corruption of a system that rewards some felons in order to prosecute certain other felons. In the case of Whitey, who ran South Boston’s Irish gangs with near-impunity for decades--unmolested by the officers whose palms he greased--the feds apparently fooled themselves into believing that he was more valuable as an informant who could rat out New England’s Italian mafia than as a criminal defendant.

It turns out that if Bulger was indeed an informant--an allegation that he vehemently denies in a jailhouse phone call to his defense lawyer (a conversation, or rather a naked spin session, on which Berlinger’s crew was permitted to eavesdrop)--he was surely a lousy informant. A 750-page government file summarizing his purported conversations with corrupt FBI special agent John Connolly--much of it repetitive and nonspecific--indicates that he provided zero actionable intelligence that led to a prosecution.

If Bulger was engaged in a Faustian bargain with the Justice Department and the FBI, exchanging information for protection from prosecution, he clearly got the better end of that deal. The sweetheart arrangement ended in the 1990s when federal prosecutors finally wised up and went after Bulger, in due course sending his corrupt accomplice, the FBI's Connolly, to prison for 40 years.

“The government was in the business of picking who should live and who should die--and that’s not the proper role of government,” Berlinger says. “It’s institutional corruption, systemic corruption, it’s turning a blind eye to reasonable standards…As long as getting into bed with criminals and murderers as confidential informants is the mother’s milk of criminal investigations, it’s going to lead to bad results.”

Historically, the FBI had been nursing a sore spot concerning the mafia, which J. Edgar Hoover long denied existed until he was embarrassed by a congressional hearing in 1963 that featured the sensational testimony of Italian mobster Joe Valachi, who introduced the term “Cosa Nostra” into the American pop-cultural lexicon. Suddenly a chastened Hoover made the Italian mafia Public Enemy No. 1

“In Boston, they said, ‘we’re gonna look the other way’ and let the Irish mobsters run roughshod over innocent victims, with law enforcement saying they were casualties of war and gangsters anyway,” Berlinger says. “But it’s not up to the government to make those choices.”

A fascinating wrinkle in the Whitey saga--one that is only glanced at in Berlinger’s nearly two-hour film--is the fact that the mob boss’s younger brother, Billy Bulger, happened to be one of the Bay State’s more powerful public officials. Billy was president of the Massachusetts State Senate and later president of the University of Massachusetts higher education system until Gov. Mitt Romney forced him to resign in 2003 after he admitted taking clandestine phone calls from his fugitive big brother.

Years earlier, Whitey had been tipped off to his impending indictment and arrest by FBI agent Connolly, and in June 2011, after a decade and a half off the grid, he was finally collared along with his longtime girlfriend, Catherine Greig, in Santa Monica, Calif.

“I can’t tell you whether or not Billy Bulger actually played a hand in his brother’s criminal career or vice versa, in terms of actual physical acts by either,” Berlinger says, noting accounts that “Whitey intimidated people to help his brother. Just the idea that these two guys were brothers would put fear in the hearts of some people that they better not go up against Whitey because they’ll face retaliation from Billy. I’m sure there were people who feared taking on Billy because of literally physical retaliation from Whitey. Billy Bulger went in front of 10 grand juries and nothing stuck. But at a certain point, perception becomes reality.”