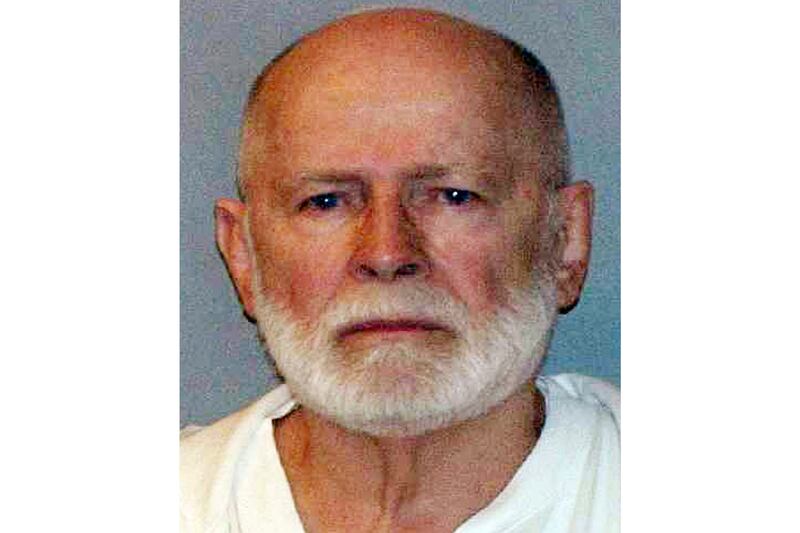

He was escorted into the courtroom, a wrinkled old codger, with little indication that he once made grown men literally piss their pants in fear. His manner of walking is now more a shuffle than a strut. James “Whitey” Bulger, alleged criminal mastermind, mob boss, street hoodlum, longtime fugitive from the law, has finally arrived at his moment of reckoning at a defense table in courtroom No. 11 at the Moakley Federal Courthouse on the South Boston waterfront.

Just a few short miles from where Bulger once allegedly controlled the city’s criminal underworld, opening statements were delivered today in the most explosive organized crime trial ever to take place in this city. Whitey stands accused in a 32-count indictment that alleges he ran a racketeering enterprise from 1975 to 1995 that was second-to-none in New England. Bookmaking, dope peddling, extortion, gun trafficking, money laundering, and at least 19 acts of murder are attributed to a man who has been characterized as a Machiavellian gangster and ruthless serial killer. Now, at age 83, stripped of his “street cred” and power, he is the Incredible Shrinking Man, a physically diminished former gangster with a bad heart and few friends or advocates beyond an imprisoned girlfriend and a defense attorney who, though highly capable, is in the position of Hans Brinker, the Little Dutch Boy with his finger in the dyke, facing a tidal wave of incriminating evidence.

The true manifestation of Bulger’s powerlessness is the manner in which he is forced to sit mute, as Assistant U.S. Attorney Brian T. Kelly excoriates the former mob boss. Bulger was “a hands-on killer,” proclaims Kelly, delivering the government’s opening statement in workmanlike fashion, focusing primarily on the unseemly details of the mobster’s many alleged murders.

ADVERTISEMENT

Bucky Barrett, a Southie criminal, ran afoul of Bulger when he sought to hide the lucrative proceeds of a jewelry heist. Said Kelly, “This man here, Bulger, shot him in the back of the head.” Eddie Connors, a local hood, “couldn’t keep his mouth shut,” a prerequisite of anyone who did business with Bulger. Connors was lured to a phone booth, and then, said Kelly, “Death came calling in the form of this man over here”—he points at Whitey—“who riddled the phone booth with bullets.” John McIntyre was suspected of being a rat, so Bulger first tried to strangle him with a rope that was too thick; McIntyre gagged but did not die. “You want one in the head?” Bulger allegedly asked. “Yes, please,” said McIntyre. So Whitey shot him in the head.

During Kelly’s opening statement, Bulger sat mostly motionless. The man who was said to be able to instill terror in people simply by fixing them with a steely-eyed glare, now mostly looks at his hands, or stares straight ahead into blank nothingness, which is possibly all the future holds for him.

The government’s case is a litany of murders. Kelly did mention that “Bulger was one of the biggest informants in Boston.” But mostly the government’s interpretation of the evidence betrays a willful lack of interest in the full details of Bulger’s deal with the U.S. Department of Justice. The government prefers to dig no deeper than FBI Special Agent John Connolly, Bulger’s direct handler, and John Morris, Connolly supervisor, who have been established as corrupt agents in previous Bulger-related trials. Those above Connolly and Morris who may have authorized and protected Bulger’s role as a top-echelon Informant is a Pandora’s box the prosecution would rather not open.

Enter J.W. Carney Jr., Bulger’s public defender. With his bald pate and white beard, Carney somewhat resembles Whitey—a thicker and younger version, with a mind and reasoned mode of articulation that Bulger, allegedly a voracious reader of books, could only dream of having cultivated and possessed. Carney cut to the chase, proclaiming within the first two minutes of his opening statement that Bulger wasn’t even an “informant,” at least not as Bulger’s enemies and the government characterized it in the 16 years that Whitey was on the lam.

Bulger was not in a position to inform on the Italians, said Carney, because he’s Irish. And to the Irish, due to “the Troubles” in Ireland going back generations, to be an informant is the lowest form of life. Bulger could never be an informant against his own people, suggested Carney, because it would be a violation of his self-identity as an Irishman. He could, however, be a racketeer specializing in bookmaking, gambling, drug dealing, and assorted other crime. The most startling aspect of Bulger’s defense is that he will admit that he committed many of the crimes of which he is accused (except for the murders), but will claim he did so because he was protected through a corrupt relationship with the criminal justice system in New England that involved many cops, agents, and prosecutors beyond Connolly and Morris.

Among other things, Carney laid out the historical precedent for the Bulger era in a corrupt relationship between mobster Joseph Barboza, one of the FBI’s first top-echelon informants, and the entire criminal justice system in New England. Protected by his handlers, Barboza testified in a notorious 1960s murder case at which, with the full knowledge of FBI agents, prosecutors, and even some judges, he fingered four men who were innocent of the crime. The men were convicted at trial. Two of those men died in prison, and two others served 30 years before it was revealed that they had been framed not only by a murderous gangster, but also by a corrupt system that had enabled and partly created the gangster Barboza.

Sound familiar? Carney is hoping that this history lesson will help illustrate that Whitey Bulger did not corrupt the criminal justice system in New England, he merely plugged into an already corrupt system and played it for all it was worth.

The trial is expected to last nearly four months. Judging from the opening statements, regardless of the verdict, when this trial is over the city of Boston will never be the same again.