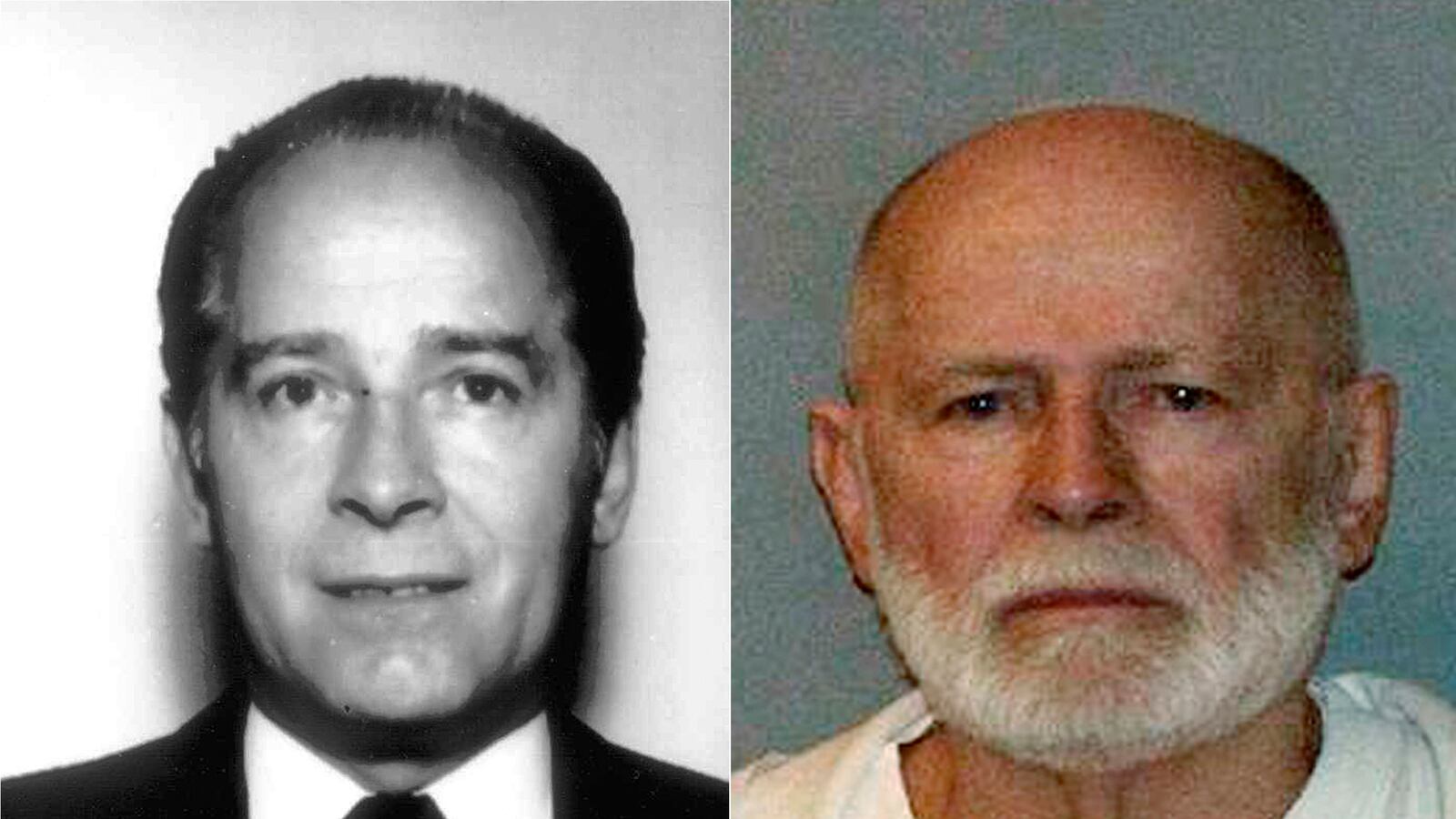

In the ongoing trial of infamous mobster James “Whitey” Bulger, we learned much of what we need to know about the government’s case on Monday when ex-FBI agent Robert Fitzpatrick took the stand. Fitzpatrick is one of the few representatives of the U.S. Department of Justice who ever tried to close down Bulger as an informant back when Whitey was wreaking havoc and killing people in the Boston underworld of the 1980s. For his efforts, Fitzpatrick met resistance at every turn, and, after a distinguished 21-year career, was eventually drummed out of the FBI.

Now, decades later on the witness stand, he was being pummeled by a vengeful inquisitor from the same Justice Department for whom he once served as a dutiful public servant.

“You’re a man who likes to make up stories,” said prosecutor Brian Kelly, his voice dripping with scorn. “For years, you’re a man who tries to take credit for things he didn’t do, isn’t that correct, sir?”

Fitzpatrick is a no-nonsense kind of guy, cut from standard FBI cloth, except for a slight variation. Unlike most FBI agents, either retired or still on the job, he does not wear the uniform of the professional bureaucrat: the standard-issue, drab suit and functional tie. In fact, Fitzpatrick wore no tie at all, one indicator that he long ago left the reservation. One of the reasons he was now being so aggressively savaged on the stand was that he dared to put forth a narrative saying that many people within the U.S. criminal-justice system are guilty of having enabled and protected Bulger during his long reign as a crime boss.

Fitzpatrick’s story is not exactly new. In 2011, he published a book called Betrayal about his experiences in the Boston office of the FBI, and he has testified at many Bulger-related hearings and trials over the years. As an assistant agent in charge in Boston from January 1981 to late in 1986, he had a ringside seat during one of the most egregious eras of corruption in FBI history. Even so, Fitzpatrick was not called to the stand by the prosecution, which preferred to use as its star witness John Morris, former supervisor of the FBI’s Organized Crime Unit in Boston. Morris, who received immunity from prosecution for his testimony, was a special agent so obsequious in his corruption that for a bottle of wine and airplane tickets for his mistress—paid for by Bulger—he would gladly have dropped to his knees before Whitey and then thanked Bulger for the privilege by cooking the mobster and his partner Steve “the Rifleman” Flemmi dinner at his home in lovely Concord, Massachusetts.

Last Friday, the government rested its case after having called 60 witnesses. Fitzpatrick was the first witness called by the defense, which is seeking not so much to prove Bulger not guilty of the 32-count indictment for which he stands accused, but to establish that he committed his crimes in consort with a corrupt criminal-justice system. Eight weeks ago, in his opening statement, defense attorney J.W. Carney admitted that “the evidence will show that Bulger is a person who had an unbelievably lucrative criminal enterprise in Boston. He was making millions and millions of dollars. He had people on the local police, the state police, and especially federal law enforcement on his payroll.” The value of this corrupt relationship, as Carney has reminded the jury throughout the trial, is that “during the period of time covered throughout this indictment, from 1972 to approximately 1995, James Bulger was never once charged with anything by a federal prosecutor in this town. Not once, not anything.”

Bob Fitzpatrick was crucial to the defense argument. As he described it from the stand in his direct testimony, he was sent to Boston in 1981 because “there was a territorial dispute up in Boston that involved state police, local police, and the FBI.” Fitzpatrick was supposed to assess the situation in Boston and make recommendations to straighten things out.

When he got to Boston, as part of his mandate, he had his subordinate, John Morris, take him to meet the OC unit’s star informant, Whitey Bulger. Fitzpatrick met Bulger at Bulger’s condo in Quincy. He was not impressed. “I met the guy, put out my hand to shake his hand, and he wouldn’t shake it. I thought, ‘Oh, that’s not good.’” Immediately, Fitzpatrick got the impression that Bulger was controlling the relationship with Morris and Special Agent John Connolly, who was Bulger’s “handler.”

Within days of that meeting in 1981, Fitzpatrick wrote out a two-page report recommending that Bulger be “closed” as an informant. Not only was Fitzpatrick’s recommendation ignored, it ignited a long process of frustration for the agent that was rekindled with his excoriation at the hands of prosecutor Kelly on Monday.

“That’s a baldfaced lie,” yelled Kelly at one point when Fitzpatrick claimed to have been among the arresting officers of Gerard Angiulo, boss of the Boston mafia, in 1986 at Francesca’s restaurant in the North End. “You weren’t even there,” said Kelly.

“Were you there?” asked the astonished former agent.

Kelly produced an FBI report of the arrest that listed the names of two agents. “These are the men who arrested Jerry Angiulo, isn’t that right, Mister Fitzpatrick?”

“Yeah, I was their supervisor,” answered Fitzpatrick. “I was there. I don’t care what this report says.”

The tone and tenor of Kelly’s attack on Fitzpatrick was beyond anything experienced by a witness so far in this case—and that includes witnesses who have admitted to 22 murders, stabbings, dismemberments, sexual molestations of stepdaughters, all manner of racketeering, and corruption on the part of federal agents that includes taking bribes and conspiracy to commit murder.

The key to understanding the prosecution’s need to discredit Fitzpatrick could be found in the former agent’s direct testimony. Fitzpatrick described how in 1982 he played a role in supervising the cooperation of Brian Halloran, a hood with ties to Bulger’s criminal organization who was serving as an informant for two FBI agents. When agents Morris and Connolly learned that among the information that Halloran passed along to the other agents was that, in the city’s criminal underworld, people were speculating that Whitey Bulger was an FBI informant, following a common pattern they leaked this information to Bulger.

“There were rumblings in the street about Halloran, that he was talking to the FBI,” said Fitzpatrick. “We received concrete information that he may be killed … We knew we had to get him into the witness-protection program. He was in harm’s way.”

To get Halloran into WITSEC, Fitzpatrick needed the approval of Jeremiah O’Sullivan, head of the Federal Organized Crime Strike Force, which was a division of the U.S. Attorney’s office. What Fitzpatrick did not know was that O’Sullivan had already been co-opted by Morris and Connolly. He was a Bulger protector high up in the system. O’Sullivan said, essentially, that Brian Halloran was not worth protecting. He denied the lowly hood access to witness protection.

So Fitzpatrick went over O’Sullivan’s head. He contacted William Weld, then U.S. Attorney for the District of Massachusetts and later governor of the state. Weld was a political compatriot of Sen. William Bulger, Whitey’s younger brother, who was president of the state Senate. Weld was a regular at Billy Bulger’s popular St. Patrick’s Day breakfast, an annual event where politicians from around the state and even the country stopped by to sing Irish songs and metaphorically kiss the ass of the powerful senator from South Boston.

Weld turned down Halloran as a candidate for the witness program.

Two days later Halloran was murdered by Bulger in a drive-by shooting on the South Boston waterfront.

Jeremiah O’Sullivan is deceased and William Weld is not talking, but Bob Fitzpatrick makes it clear that he believes these high-ranking officials in the U.S. Attorney’s Office, acting in consort with Morris, Connolly, and, by extension, the Bulger brothers, are partly to blame for the murder of Brian Halloran.

There were other murders. As described in earlier testimony by hitman John Martorano, within months of Halloran’s death Bulger’s Winter Hill gang would commit murders in Oklahoma and Miami. These two murders were connected to the gang’s control of World Jai Lai, a pari-mutuel betting racket of which Winter Hill had been publicly linked in investigative newspaper reports. To Fitzpatrick, it was becoming painfully obvious that Whitey Bulger was whacking people left and right, knowing full well that powers within the criminal-justice system were willing to cover for him.

In May 1982, Fitzpatrick was called to a major FBI powwow in Washington, D.C., involving some of the highest-ranking supervisors at FBI headquarters. He was startled to learn that rather than being concerned that one of their top-echelon informants was possibly killing people, the supervisors were more concerned about protecting Bulger’s identity from public scrutiny.

In the Bulger saga, culpability within the criminal-justice system spreads far and wide. Ever since it was first revealed in the late 1990s that Bulger and Flemmi had both been informants for more the 20 years, the U.S. Department of Justice has been engaged in damage control. Throughout the Bulger trial, prosecutors Brian Kelly and Fred Wyshak, along with attempting to prosecute Bulger to the fullest extent of the law, have been seeking to contain the evidence. In their version of the facts, Bulger was enabled by a dastardly squad of corrupt rogue agents, led by John Connolly, and the conspiracy goes no higher than that.

Fitzpatrick is the first witness to broaden the scope of corruption beyond the local FBI office to include FBI headquarters and the U.S. Attorney’s office in Boston—the very office now prosecuting Bulger for his crimes. Judging by the ferocity of the cross-examination of Fitzpatrick by Prosecutor Kelly, acting as bullyboy for a system whose methods have been called into question, there is a price to be paid for going against the grain.

Fitzpatrick’s cross-examination continues Tuesday