James “Whitey” Bulger is Boston’s most notorious gangster. His racketeering empire grew from the 1970s through the 1990s, and no matter what crimes he committed—including multiple murders—he never faced charges. The reason: he was protected as an informant by the Boston office of the FBI. After being tipped off in 1994 by his handler, agent John Connelly, about a new indictment, he went on the run. Bulger was finally captured in June 2011 and awaits trial in Boston.

Bulger’s terrorizing of Boston damaged the bureau’s reputation, and for good reason. A civilized society does not condone the protection of a killer simply because he can provide some information about organized crime. As the activities of the FBI became exposed in a federal criminal proceeding of Bulger’s associates in the late 1990s, the families of the victims learned of the duplicity and corruption of the FBI. One by one, they filed lawsuits against the government, to little success. They were denied any recovery because their cases were deemed by the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit to have been filed too late, thus rewarding "official uncontrolled wickedness" by letting the Boston FBI office "get away with murder," according to the dissenting opinions. Some of these victims were truly innocent people—a truck driver who gave someone a ride, two girlfriends of Bulger’s partner. Others were involved in Bulger’s criminal enterprise. No matter who they were, none deserved to die, nor did their families deserve to suffer from their government’s enabling of a murderer.

Of the many previous allegations, one known verdict remains intact: $3.1 million was awarded in 2006 to the family of John McIntyre.

McIntyre was 32 years old when he took a job as an engineer on the Valhalla, a fishing trawler moored in Gloucester, Mass. In a deal orchestrated by Whitey Bulger, the boat was packed with seven tons of weapons and ammunition, headed for the Irish Republican Army. Things turned bad when the ship to which the guns were transferred was seized off the coast of Ireland. Later, McIntyre was brought in for questioning. He told law-enforcement officials about Bulger’s involvement; he was “petrified” of the man who would “just put a bullet in your head,” according to court documents.

Instead of protecting McIntyre, the investigators allowed word of his cooperation to reach Bulger’s handler. The rest is the stuff of film noir: Bulger learns of a potential problem for his criminal enterprise from his most loyal and corrupt partner in the FBI. Bulger eliminates the problem permanently.

On a chilly evening in November, 1984, McIntyre left his parents’ home in Quincy, Massachusetts, to attend a party, where he was greeted by Bulger, Stephen “The Rifleman” Flemmi, and Bulger associate Kevin Weeks. McIntyre was handcuffed, shackled, and chained to a chair, then interrogated and tortured for hours. Bulger attempted to strangle McIntyre with a rope and, when that failed, he shot McIntyre in the head multiple times. Flemmi took a pair of pliers and removed McIntyre’s teeth.

In the McIntyre family’s civil lawsuit, the murder of John J. McIntyre is referred to as “the 24th known murder caused by Bulger and Flemmi since becoming FBI informants.” When McIntyre was shot, he was buried along with Arthur “Bucky” Barrett and Deborah Hussey in the basement of a South Boston home. In October 1985, learning that the house would be sold, Bulger, Flemmi, and Weeks returned to exhume the remains of the three bodies and bury them again in the Dorchester area. For the following 15 years, the FBI claimed that John was still alive and was a fugitive. It was not until Sept. 15, 1999, when Boston Federal Judge Mark Wolf issued an opinion disclosing the FBI’s involvement in the murder of John McIntyre that the family officially knew how and when John died. This mass grave was discovered in 2000.

“Bulger buried John in the seventh level of Dante’s inferno,” Chris McIntyre, John’s younger brother, told the Daily Beast in an exclusive interview.

Chris shared his pain for the first time in detail, saying that John’s murder destroyed his family. Their father, once an agent with the Army’s Counterintelligence Corps, never got over it. As he lay dying in a hospital within a year of John’s disappearance, he told Chris: “Find the guys who did this.” His mother, Emily, a naturalized U.S. citizen from Germany, who “passionately believed in the Constitution and could recite it with pride,” was baffled and frightened as she learned that the government played a role in John’s death.

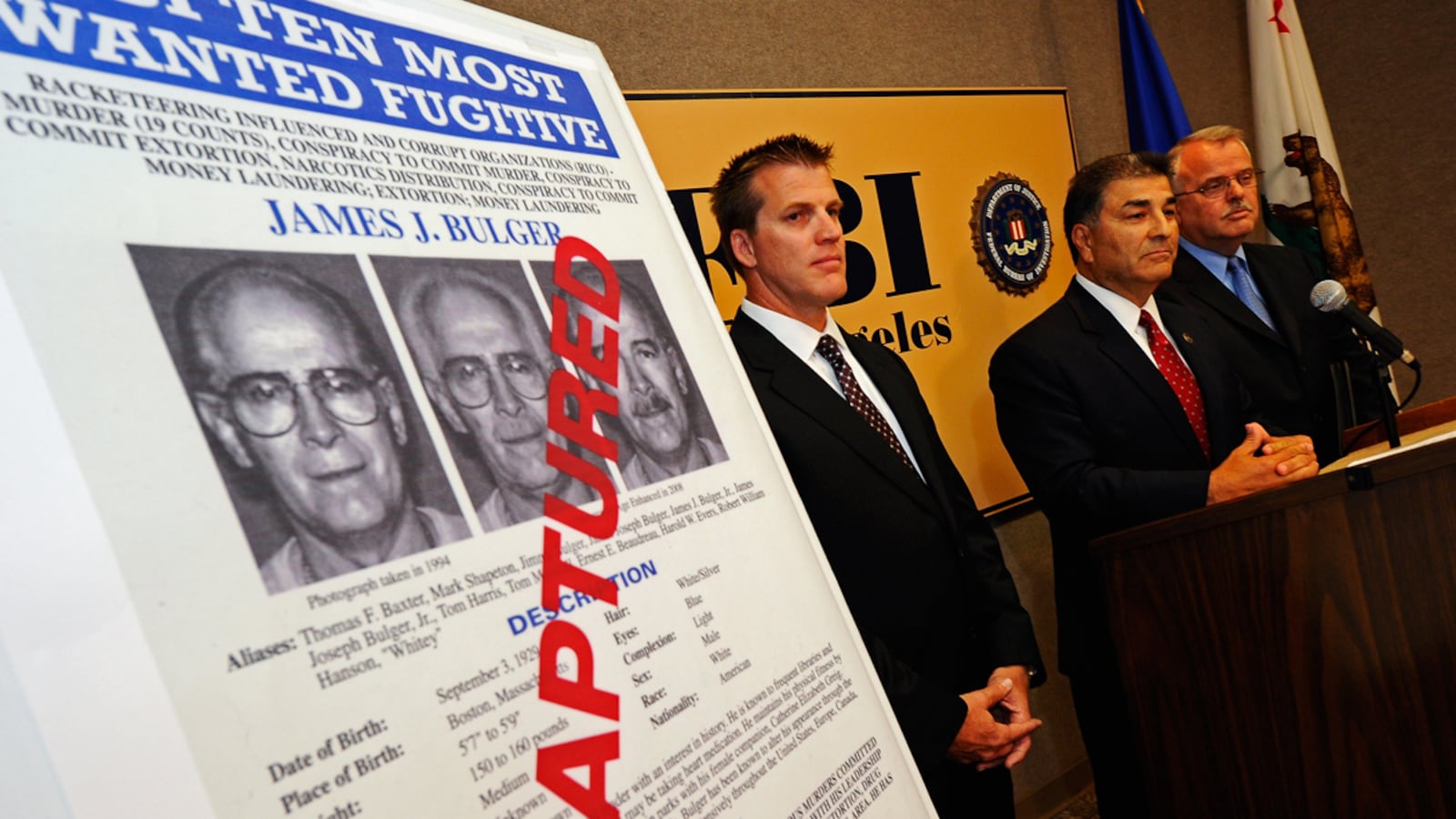

Twenty-seven years passed before Whitey Bulger and his longtime girlfriend, Catherine Greig, were captured in Santa Monica, Calif., this past June. Bulger, now 82, has since been in jail, awaiting a trial that may never come to pass during his lifetime. To say that the federal case filed in Boston is complex is an understatement. The indictment runs 111 pages and covers the years 1972-2000; there are 19 murder charges against Bulger, in addition to crimes of racketeering, extortion, loan sharking, and trafficking in narcotics. Thousands of pages of discovery material were furnished to the defense in order to prepare. Some people say the trial may begin next year; others think that is overly optimistic. Bulger was also indicted for one murder in Florida and another in Oklahoma, but the Boston case takes precedence.

Chris McIntyre wants Bulger tried in Boston “since most of the victims are here. There is so much pain in this city—there are so many victims who need to feel that somebody gives a damn about them. There are a thousand victims here—relatives, friends, what he did with drugs in this city, how many kids died, how he destroyed families. He’s a serial killer, a psychopath.”

Bulger’s impact on Boston is immeasurable. “This is a guy who put 12-year-old girls on the corner to sling their ass while he’s putting needles in the arms of 12-year-old boys,” Chris McIntyre continues. “He is the king of extortion, murder, drugs, everything in Southie. I want in the worst way to see him get at least one murder conviction. I want him to live the rest of his life in an 8-by-10 cell. The death penalty [for the murders in Oklahoma or Florida] would only be showing him mercy.”

As for FBI agent Connolly, in prison with a 40-year sentence, Chris is equally candid. “I hate Connolly. He made it possible for Bulger to kill.”

Chris McIntyre faces his own criminal charges today on gun and drug possession— though his attorneys claim that Chris is being targeted for winning the civil lawsuit against the FBI. But he doesn’t talk about his own problems; he is still focused on Bulger and how the FBI enabled him to do so much harm to so many whom the courts have rendered helpless. “I’m 52. This started when I was 24 years old. It’s taken too much. I want it to be over but I want them to clearly understand the damage they have done to people. We were normal once upon a time.”

There is no solace for the McIntyre family in their victory against the United States government, the FBI, and its individual agents. “There is no such thing as closure,” Chris says. “There’s revenge. And I know that can’t happen.”

Chris’s lawyer Jeffrey Denner adds: “There is no amount of money that can compensate the McIntyres. John McIntyre lost his life; the McIntyre family forfeited any chance they had for a reasonable life; the City of Boston lost its unconditional sense of trust in federal law enforcement. Even an apology, were it ever forthcoming, cannot change what the government did to these people.”