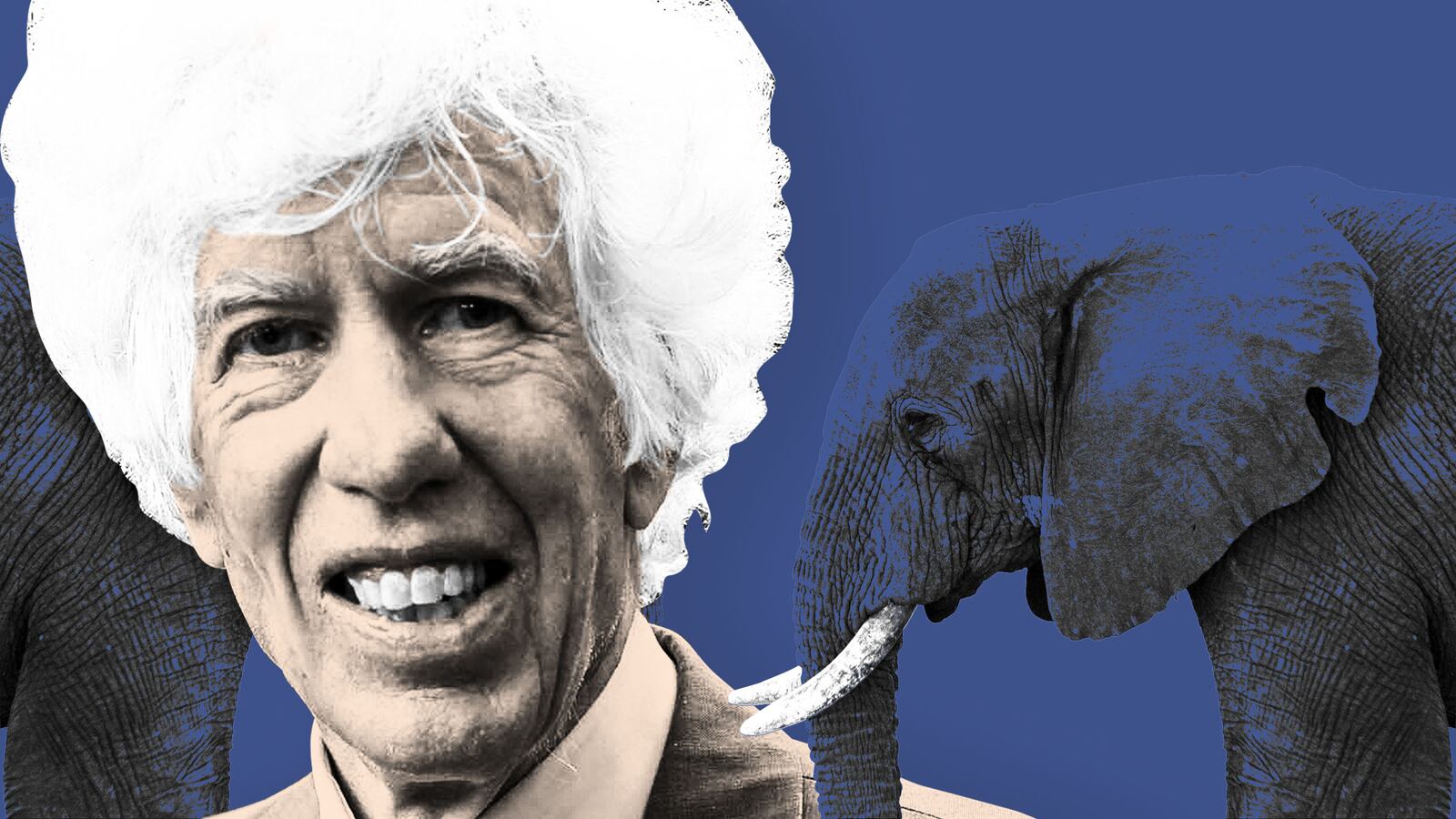

NAIROBI, Kenya—Esmond Bradley Martin was found dead on February 4, a stab wound in his neck and the floor of his home covered with blood. The famous white-haired American wildlife activist and expert on the illegal ivory trade had been murdered within the confines of his estate in Langata, a posh suburb of his adopted country's capital.

So far Kenya’s police have pursued two lines of investigation: a robbery gone wrong; a planned murder linked to Martin’s efforts to circumvent the illegal trade in wildlife.

Now a third possibility—that Martin was killed as a tactic in an attempted land grab—has come to the attention of The Daily Beast.

On that quiet Sunday afternoon, the 76-year-old veteran of East Africa’s “wildlife wars” and his wife, Chryssee, had just shared a curry lunch with friends at Nairobi's National Park. They returned home around 2:00 p.m. Chryssee went for a stroll in the wooded forests of their 20-acre, park-like property. When she returned to the house, she discovered the body of her husband on the second floor, a deep stab wound to his neck.

While foreigners don't die by violence here in Kenya as often as media coverage can make it seem, their murders are prominent and so get a big share of attention.

Martin joins the ranks of prominent activists and researchers who have met violent ends while defending or observing Africa’s wildlife in Kenya and elsewhere on the continent. Particularly well-known cases are the murders of gorilla researcher Diane Fossey, and of Joan Root, an activist who died trying to save the ecosystem of Kenya’s Lake Naivasha. One thing these murders have in common is that they remain unsolved, the killers never brought to book.

Other cases include the killings of Julie Ward, a British tourist murdered in the Maasai Mara in 1988, and Tonio Trzebinski, an artist killed in 2001.

While Kenya's police force has struggled to overcome its reputation for corruption and ineptitude, the list of unsolved murders remains long.

The Kenya government’s promise to investigate the murder of Chris Msando, the Independent Electoral Boundaries Commission’s acting information and communications advisor, has so far been unfulfilled. And the list of instantly cold cases, with the killing of Martin, may have just grown.

A specifically relevant precedent was the murder in August 2017 of 51-year-old Wayne Lotter, head of a wildlife conservation NGO. He was shot dead in Tanzania as he drove to a hotel from Dar es Salaam’s airport. Lotter’s foundation reportedly funded an elite Tanzanian anti-poaching unit, responsible for the arrest of major ivory traffickers including China’s Yang Feng Glan, known as “the Queen of Ivory,” and a slew of inglorious elephant poachers. The only item the unknown assailants took was Lotter’s laptop.

Because of Martin’s work, which often involved going undercover in remote locations around the world, the media were quick to link his murder to his activism and investigations. But others think that it was unrelated to his career. They argue that Martin was not the kind of target to draw such brutal intervention by traffickers of ivory and rhino horn.

Doubters say, sure, Martin knew who all the kingpins were. He knew how the networks operated. But he never named names. And he was 76 years old! Why would he be killed now?

Furthermore, his recent work showed the contraband trade has been shrinking. His “Decline in the Legal Ivory Trade in China in Anticipation of a Ban” (PDF) was published by conservation group Save The Elephants just last year. The report was co-authored by consultant Lucy Vigne, and showed that 130 licensed outlets in China had been reducing the quantity of ivory items on display for sale, and cutting prices to improve sales.

Police say the killing looks like no more than a botched robbery. Yet close friends and neighbors point out that little or nothing appears to have been stolen. One, who visited the scene and asked to remain anonymous, said there appeared to be no struggle on the house’s ground floor where Martin kept his office. The considerable presence of blood on the floor above, along with the presence there of the body, indicate that that is where the murder took place.

It was in the ground floor office of his house that Martin spent many hours writing reports about the ivory and rhino horn trade. Sources say the office appeared not to have been touched at any time during the attack, as if the records of his investigations were not of interest.

So, does Martin’s murder fit the profile of other apparent assassinations?

One security expert who declined to speak for attribution told The Daily Beast no. “Bumping off [Martin] with a knife in his house on a Sunday afternoon doesn't sound like a hit.” This Kenyan investigator—with over 30 years’ experience in wildlife management security and aviation—adds, “The traditional hit in Kenya is performed with a gun, far from home or the office.” Furthermore, “Esmond was an academic. His work did not involve direct law enforcement.”

While Martin’s work led him to strange and remote places, from Lagos to Laos, it remained abstract and probably irrelevant for most wildlife criminals.

Esmond Bradley Martin hailed from the monied class of the U.S. East Coast establishment. He was the great grandson of Henry Phipps, the Pittsburgh steel magnate and partner of Andrew Carnegie. Martin and Chryssee first arrived in Kenya in 1967, and built the home where he was murdered.

His talent for detail was evident soon after he arrived in Kenya. In his first book, The History of Malindi, published in 1974 (PDF) he traced the rise and fall of retail and service industries such as tourism and fishing. As one reviewer noted with more than a hint of sarcasm, “It is no trouble to Dr. Martin to measure the diameter and length of mangrove poles used for various purposes … more studies with such valuable minutiae are needed.”

Friends say his interest in the wildlife trade began as he learned about the various items being ferried on dhows from Mombasa to the Middle East, one of these items being rhino horn from Kenya bound for Yemen, where the then plentiful horn was used for dagger handles.

Martin was famous for his mop of hair, which was as white in the ‘90s when I first met him as it was when I last saw him a few years ago. Both times we discussed—over tea—the ebb and flow of the illegal wildlife trade.

He and his colleague Vigne often investigated as a pair. They’d go to remote places posing as buyers, one of them chatting up a shopkeeper while the other took inventory of wildlife products out for sale. His views and prowess were sought in the House of Commons, and by the most prestigious wildlife charities. The U.N. made him its special envoy on rhino conservation.

Dan Stiles, a Kenya-based American consultant for wildlife trade related NGOs knew Esmond and Chryssee for almost 40 years and carried out several ivory market investigations with him.

“It could have been more than a botched robbery, but unlikely it was carried out by angry ivory traffickers,” Stiles told The Daily Beast, adding, “Esmond was a dearly loved and respected member of the conservation community and he will be greatly missed.”

If a botched burglary doesn't seem to add up to a motive for murder, and if this killing wasn't related to Martin’s work, what else could it have been related to? The third possibility is land—a highly charged, emotional issue in Kenya.

This country is changing fast. Wilderness has disappeared, wildlife has declined as livestock has increased, and grassland rapidly turns into dust. The changing climate has made droughts deeper and more frequent. These chronic factors are exploited by politicians and others to escalate tribal and economic rivalries (sometimes disguised as Islamic terrorism) and to incite violence.

In the months leading up to Kenya’s recent presidential election, violent land-related incidents increased, especially in Laikipia to the north, where several large wildlife conservation ranches are located. Such properties—potentially useful for grazing and other profitable forms of development—are the focus of those who’ll go great lengths to accomplish land acquisition. The attacks on noted conservationist, Kuki Gallman, on her 98,000 acre ranch last summer is one such instance.

While it may seem strange to deem Martin’s 20 acres in Langata such a parcel, the property’s proximity to Nairobi magnifies its per-acre value. The nearby district of Karen, looking out on the Ngong Hills, was home to Isak Dinesen (Karen Blixen) author of Out of Africa. Langata, which has as its stellar denizens the likes of photographer Peter Beard, was once considered Kenya’s Wild West. These days, churches and strip malls line the main arteries coming out from the city.

In the days following Martin’s death, I stopped in front of his driveway. He’d been known for keeping this property’s gate unlocked. Now, access was blocked by that massive, ornate metal gate, an “M” perched at the top. But no such barrier could stop the ear-splitting sounds of jackhammers that seemed to be emanating from within, or very near to, the Martin property. When I drove toward the other side, a section of what appeared to be pristine forest had been sealed off. It was closed for construction.

A Langata resident provided The Daily Beast with a copy of an injunction to stop “the proposed construction [beside Martin’s property] of a church and associated facilities for religious purposes.” The petition resulting in this order, was filed by the Karen Langata District Association (KLDA). Bradley Martin was a member of the KLDA and an opponent of the church construction. Numerous residents pointed out multiple irregularities and violations in the building porject.

The cease-and-desist order was issued two days after Bradley Martin’s death, but seems to have had no effect.

A known member of the congregation of this proposed church, which is Seventh-Day Adventist, is Kenya’s current Minister of Internal Security, Fred Okengo Matiang’i. His name appears as one of two parties being told to halt construction. The other name is that of Zablon A. Mabea, the former Commissioner for Lands. So, despite the injunction, the construction continues.

Martin helped fund the effort to block the church’s installation. One Karen resident who spoke to The Daily Beast on condition of anonymity said that Martin was especially vocal in his opposition to the construction.

Very little was stolen by whoever it was who killed Martin. His phone was still on him. His safe was cracked, but gold and gems were still in it, according to the neighbor, who theorized someone organized the attack to make it look like a botched burglary. According to the London Times the only things taken were cash and property deeds.

Many critics of the government argue that close ties between the security apparatus and politicians account for the country’s high incidence of unsolved murders. “This puts us in a conundrum. You’ve got a stop order and you’re supposed to use the police to enforce the stop order—but the head of the police is involved with this church,” as one opponent of the construction put it.

Rumors and speculation continue to swirl. More than one neighbor of Martin’s reported that he’d received ongoing threats over the years relating to his land. Several years ago his night watchman was murdered.

“Esmond’s heart was like an unlocked gate,” said longtime friend and lion conservator Tony Fitzjohn.

Neighbors and their watchmen agreed on one point, Esmond should have kept his real, iron gate locked.