Arthur Shapiro was in trouble. The shy, secretive lawyer—a partner in the Columbus, Ohio firm of Schwartz, Shapiro, Kelm & Warren—was under investigation by the Internal Revenue Service for failing to file income tax returns for seven years and for possible investments in shady tax shelters. In March 1985, Shapiro was due to testify before a grand jury over his tax dodging—and whether anyone had helped him hide money. What he might reveal, no one knew, but he and his firm had several high-profile clients and a long history in Columbus.

But Arthur Shapiro never made it to the stand. A day before his scheduled testimony, someone fired two bullets point-blank into his head as he fled from a secretive breakfast meeting—held in his red BMW—at a Columbus cemetery.

The mob-style murder has never been solved.

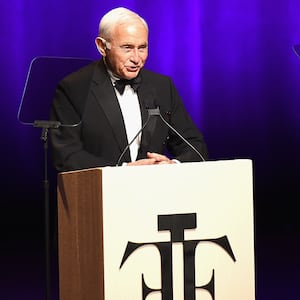

Shapiro reportedly personally oversaw the account for The Limited, the clothing company owned by billionaire Les Wexner whose empire also included popular brands like Lane Bryant, Express, and Victoria’s Secret.

Neither Wexner, whose communications team declined to comment for this piece, nor anyone tied to him were ever thought to be involved in Arthur Shapiro’s death. Instead, a business partner of Shapiro’s was the prime suspect.

The case’s curious twists and turns, though, would result in a controversial police report that accused some of Wexner’s business associates of having mob associations. Shapiro’s name would also appear decades later—seemingly as a red herring—in an FBI file involving the activities of another man important to Wexner’s business: the pedophile financier Jeffrey Epstein.

But for the most part, Arthur Shapiro’s death became just that—a footnote in a bureaucratic file—and it remains a mystery to this day.

On the morning of March 6, 1985, the day before Arthur Shapiro was scheduled to testify before a grand jury, he was spotted in his red BMW, parked in a cemetery, while sharing a carryout breakfast with an unidentified man.

A few minutes later, his breakfast companion—described by a witness as a man dressed in black with a broad-brimmed hat and running with a limp—chased Shapiro from the car while firing shots from a handgun. Shapiro made it to the door of a nearby condo, where he pounded several times before he was shot twice in the head at close range.

Shapiro was 43 years old when he was murdered in what the police would later describe as a mob-style hit, while his assailant escaped in his red BMW.

Russell Kelm, who had worked at Schwartz, Shapiro, Kelm & Warren, said none of the partners had been aware that Shapiro was the target of an IRS investigation until after the murder. While police reports described Shapiro as “a quiet, shy, private, secretive person” who “tended to be a ‘loner,’” Kelm told The Columbus Dispatch in 2010 that Shapiro was the reason he joined the law firm. “He was the kind of guy you could sit down with over a beer after work and talk for hours.”

Kelm was tasked with determining whether the homicide was related to Shapiro’s work with the firm. After Shapiro’s widow showed Kelm bags of documents in their basement, many related to the IRS investigation, Kelm said, “That’s when we started to see what this was about.”

In 1991, the Columbus Ohio Police Department’s Organized Crime Bureau asked a civilian analyst to write a memo on the investigation into Shapiro’s murder. The secret report was so explosive that a police chief reportedly ordered it to be destroyed. But a local investigative journalist, Bob Fitrakis, got ahold of the findings when they were accidentally released through a public records request, and published the results in an article for the alt-weekly Columbus Alive.

The police department’s investigation memo noted that Shapiro had been a partner in the law firm of Schwartz, Shapiro, Kelm & Warren, which represented The Limited, and that prior to his death “Arthur Shapiro managed this account for the law firm.” The memo went on to speculate that the grand jury questioning could have put Shapiro in a sticky situation, to possibly face disclosing information damaging to other parties.

The memo also linked the firm’s client Les Wexner to business dealings with a range of figures allegedly tied to organized crime. (The report, however, does not go further to accuse Wexner of any involvement with the Shapiro murder.)

The memo concluded that the motive for Shapiro’s murder was unclear, but that whoever killed the lawyer knew him professionally or personally, would benefit from his death, likely had close contact with mafia figures, and had the financial resources to afford a contract killing.

One of the main suspects in Shapiro’s murder was an accountant named Berry Kessler, who had worked with Shapiro and was under scrutiny for helping him set up bogus tax shelters. Two of Kessler’s employees told The Dispatch that the day after Shapiro was murdered, they saw Kessler counting a large pile of money, before a man matching the killer’s description visited Kessler’s office. (Kessler and two associates pleaded guilty in 1986 to helping Shapiro fake his tax returns.)

Kessler eventually ended up in prison for hiring a hit man to kill another business partner in Florida, and for plotting to bump off yet another business contact. (He also was suspected of murdering yet another business partner and the man’s fiancée in Columbus in the 1970s.) But Kessler died behind bars without ever admitting to Shapiro’s slaying.

Five years after the release of the Shapiro memo, a mayoral investigation accused Columbus Police Chief James G. Jackson and other members of his department of trying to destroy the Shapiro report, and slapped Jackson with a suspension. Jackson admitted to destroying the document—but said the report’s theories, about mafia ties involving prominent citizens of Columbus, were highly speculative and not based on hard evidence.

Still, as the report noted, it was ordered in the first place “because of the strong similarities between this homicide and a Mafia (L.C.N.) [La Cosa Nostra] ‘hit’.”

Much of the information in the 1991 police memo on the Shapiro homicide spans several years after the 1985 murder and shows links from some Wexner companies and associates—including Harold Levin, John Kessler, and Robert Morosky—to entities allegedly associated with organized crime, as displayed in the 1985–1990 diagram below:

The memo described relationships among various entities which all linked directly or indirectly to Wexner, including: The Limited (Wexner’s company); Walsh Trucking (which contracted with The Limited); the firm Schwartz, Kelm, Warren & Rubenstein; Omni Exploration (owned by Wexner’s company Lewex Inc.); Edward DeBartolo (who partnered with Wexner on a few failed takeover bids); and John Kessler (Wexner’s partner in The New Albany Company where Epstein was later co-president).

The memo noted that a senior executive at The Limited, Robert Morosky, had worked directly with Arthur Shapiro. Morosky had been the vice chairman of The Limited until he resigned in 1987. A Wall Street Journal article from the same year said Morosky had been close to Wexner and many were surprised by his departure. Some speculated it may have been due to his association with Frank Walsh at Walsh Trucking, which worked for The Limited, at one time handling up to 90 percent of its trucking business and appearing to share the same address:

“Industry sources suggested that one possible factor precipitating Mr. Morosky’s resignation was his association with Walsh Trucking Co.’s Frank Walsh, who is under investigation in several cities for alleged payoffs and anti-competitive practices. Limited, which has been a major client of Mr. Walsh, has been reducing its contracts with Walsh Trucking in favor of other shippers lately.”

The Fitrakis article noted that Walsh was charged in 1988 with making “illegal pay-offs to reported mob figures and officials of Teamster Local 560.” The indictment named as “unindicted co-conspirators” Genovese crime family kingpin Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno, mafia boss Matthew “Matty the Horse” Ianniello, and the Provenzano brothers, “convicted of various charges in the past and linked in media accounts to the murder of former Teamster President Jimmy Hoffa.”

Despite the scrutiny on his business and his reported mob ties, Walsh was still moving goods for The Limited in 1990, according to the Shapiro homicide memo. There’s no indication in the memo that Wexner’s business dealings with Walsh were anything but legitimate, or that Wexner knew of Walsh’s alleged payoffs to the Teamsters.

Wexner also had a close business relationship with Eduard DeBartolo Sr., who was rumored to have links to the mob. In 1984 and again in 1986 Wexner partnered with DeBartolo in hostile takeover bids for Carter-Hawley-Hale stores, which owned Nieman-Marcus and Bergdorf Goodman. (As with Walsh, there’s no evidence in the report that Wexner’s business deals with DeBartolo were untoward.) A 1986 L.A. Times story described how DeBartolo Sr. was “repeatedly investigated by federal authorities for connections to organized crime. In the 1950s and 1960s, a number of bombings against properties he owned added to rumors of mob ties.” A secret government tape recorded in 1989 and played in U.S. District Court included claims by Ernest “Rocky” Infelice that Chicago mobsters had convinced DeBartolo to withhold financial support for a Chicago mayoral candidate.

The Shapiro homicide memo stated that both Walsh and DeBartolo were “considered associates of the Genovese/LaRocca crime family.”

DeBartolo was also a close business partner of Paul Bilzerian, a corporate raider convicted of fraud in 1989 and father of Instagram star and NRA advocate Dan Bilzerian. In 1998 DeBartolo Sr.’s son, Eddie DeBartolo Jr., pleaded guilty to failing to report a felony in a bribery case. In 2020 he was pardoned by then-President Donald Trump.

While the 1991 Shapiro homicide memo investigated many people and entities connected to Wexner, the main suspect in Shapiro’s murder remained his former business associate Berry Kessler (no relation to Wexner’s partner John Kessler), who died in prison around 2005.

Kessler was an accountant associated with a long history of criminal activity, including tax and insurance fraud. He was suspected of multiple murder plots against business partners and ultimately convicted of one of the murders-for-hire. A judge, who handed Kessler a death sentence, noted, “You, in a most cold and calculated fashion, plotted and carried out a contract-style murder of a man who thought you were his friend. You are, in fact, a clever, cunning, and merciless killer.”

In 1986 the Indianapolis Star described the allegation that Kessler helped Shapiro evade payment of federal income taxes from the years 1971 to 1979. Kessler was indicted in an income-tax evasion plot along with William Hatfield and Albert Maxwell. “It is alleged that Hatfield and his co-defendants aided Shapiro by helping create documents which made it appear as if Shapiro invested in a tax shelter involving cattle and book publishing, thereby eliminating any tax liabilities for Shapiro,” the Star noted. “The indictment states that no such tax shelter investments were made by Shapiro.”

Columbus police detective James McCoskey had tried to coax a confession from Kessler and sent him a letter in prison encouraging him to provide closure for Shapiro’s family. But instead he “got a letter back that basically told me to dip my knuckles.”

Robert Schwartz, son of the founder of the firm where Shapiro worked, told The Daily Beast his father was convinced Kessler was behind the killing.

“What my father told me, so this is hearsay, was this was Kessler’s M.O.,” he said. “Kessler produced some tax returns to which the IRS cocked a snook, as they say, and they were going to call Arthur before a grand jury, and Arthur had agreed to testify, in return for considerations, I don’t know what.” Schwartz added that they believe Kessler murdered Shapiro “so he would not testify to the grand jury about Kessler’s machinations.”

Though Arthur Shapiro’s murder, and the later police memo on it, made news at the time, eventually they faded from view. But Shapiro’s name would resurface decades later in an FBI file tied to Jeffrey Epstein.

About a year after Shapiro’s murder, Epstein stepped into Wexner’s life. A former math teacher and college dropout from New York, he had a head for numbers, had worked briefly on Wall Street and with Ponzi schemer Steven Hoffenberg, and liked to tell people he dabbled in international spycraft.

Wexner hired Epstein in what would become a decades-long partnership, one that the Columbus magnate dissolved after revelations that Epstein ran a sex-trafficking operation and preyed on underage girls, including models who worked for Victoria’s Secret. But starting in the early 1990s, Epstein grew his fortune by the multi-millions thanks to his partnership with Wexner.

Epstein’s name also appeared as an officer on companies that Wexner dissolved in the early 1990s, all of which had originally been set up by Shapiro’s firm.

Epstein’s fortunes rose significantly when he met Wexner. Wexner’s close friend and insurance mogul Robert Meister introduced him to Epstein in 1986 and in 1990 Meister’s wife introduced Wexner to Abigail Koppel, who he wed in 1993. Later Meister changed his opinion of Epstein and told Vanity Fair that he and his wife warned the Wexners to stay away from Epstein, to no avail.

Harold Levin, who became a financial adviser for Wexner in 1982, said he met Epstein in 1989 and quit a few months later when Epstein was put in charge of Wexner’s finances. Levin claimed Epstein spread rumors that “Wexner had fired him for misappropriating funds” and said “Epstein ruined my life. I lost everything.”

In an interview with The Daily Beast, Levin insisted that the author of the police memo “didn’t know shit from apple butter.” He maintained that none of the companies that he helmed on Wexner’s behalf were tax shelters: he and Wexner had made an honest attempt to turn a profit at Omni, but plunging oil prices undercut them, he said.

“It was a straightforward business transaction,” Levin said. “There was a good, solid business plan behind it.”

According to Levin, Wexner established PFI Leasing to allow friends to rent his collection of old Rolls Royces.

Levin recalled Shapiro as a “nice guy,” but said he did not remember him attending any board meetings regarding Omni, or having had any role beyond filing basic paperwork. He further asserted that Wexner never had any shady business connections during the seven years he worked under him—that is, until Wexner hired a new financial adviser from New York.

“I never saw Wexner do anything illegal or unethical,” he said. “Unfortunately, he met this guy Epstein.”

The New York Times reported that after Epstein started working for Wexner, longtime colleagues and friends “soon found themselves getting iced out of his life.” Jim Duberstein, who had invested in real estate with Wexner, said shortly after attending a meeting with Epstein he was cut out of Wexner’s life.

Sources told Vicky Ward that Epstein had proved he could be useful to Wexner with “fresh” ideas about investments and that “Wexner had a couple of bad investments, and Jeffrey cleaned those up right away.”

Within a few short years, Epstein had become so close to Wexner that they were buying property together—including one of Manhattan’s most palatial and expensive Upper East Side townhouses—and Epstein was named Wexner’s power of attorney over all his legal and financial matters.

In 2005, Alfredo Rodriguez was working as house manager and butler at Epstein’s Florida residence. Rodriguez was arrested by the FBI in 2012—several years after Epstein was convicted in Florida of soliciting sex from an underage girl—when he tried to sell Epstein’s infamous Little Black Book, the bombshell record of Epstein’s powerful friends, for $50,000. Rodriguez was charged with obstruction and sentenced to 18 months in prison — incredibly, the same sentence Epstein received.

While skimming Rodriguez’s FBI file, I found a memo from a 2010 interview with the Columbus Police Department about the Arthur Shapiro murder:

The information on Shapiro in Rodriguez’s file does not seem to be directly connected to Epstein — it appears that during FBI interviews related to Rodriguez, someone offered information about the Shapiro murder separately and a follow-up interview was conducted by the FBI with the Ohio police department. It does not appear that anything came of this follow-up interview.

There’s no clear indication where the information on Shapiro came from. But in Rodriguez’s FBI file, the sections about the side investigation into Shapiro’s homicide, which reference murder suspect Berry Kessler, included notes about an unidentified source at the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) with the notations “NERO FTD”—which are likely abbreviations for ‘Northeast regional office’ and ‘Fort Dix.’ Epstein’s former associate, the Ponzi schemer Steven Hoffenberg, was incarcerated at Fort Dix until 2013. (Hoffenberg declined to comment to The Daily Beast.)

The 2010 FBI interview includes some details that were not in the 1991 police memo, which had noted that Shapiro had supposedly worked on Wexner’s The Limited account and had invested in tax shelters and could provide testimony to a Grand Jury “that would have been damaging to some other party.”

The 2010 memo in Rodriguez’s FBI file goes further and directly links Shapiro to fraudulent business activity at the firm where he worked and to helping others create illegal tax shelters:

“It was determined that Shapiro was involved in misconduct and fraudulent business activity with the firm where he was employed. Specifically, it was believed Shapiro was helping businessmen purchase companies that were facing bankruptcy and creating illegal tax shelters.”

Despite the report’s note, there has been no other reporting showing that Shapiro or the firm he worked for helped anyone, including Wexner, create illegal tax shelters.

There’s no indication that Shapiro and Epstein ever overlapped in Wexner’s employ. But some of the companies that Shapiro’s firm helped set up were later dissolved by Epstein, providing another glimpse at what the pedophile financier was doing in his work for Wexner in the 1990s.

The 1991 Shapiro homicide memo described how Wexner controlled a company called Samax Trading, incorporated in July 1985 (and later renamed Lewex Inc.), that acquired 70 percent of Omni Exploration, an oil and natural gas company.

There were three companies named Lewex Inc. registered in Ohio by Wexner’s law firm: one dissolved in 1979; another one acquired Omni Exploration and a few years later listed Jeffrey Epstein on dissolution papers; and the other was renamed Parkview Financial — a company later involved in two Epstein real estate deals in New York City.

A 1988 story from The Oklahoman reported that “Leslie Wexner and affiliates own 67 percent of Omni and still will own more than 50 percent after 5 million Omni shares are issued to FBB Anadarko, said Omni president Gary Novinskie.”

There is no evidence of any illegal activity related to the Omni Exploration deal.

But before Lewex Inc. acquired the majority stake in Omni Exploration, Omni had recently come out of bankruptcy. The co-founder of Omni-Exploration, Bruce Trainor, was knowledgeable about tax shelters and was described as “one of the most successful shelter consultants.”

In 1992 the Wall Street Journal reported that 64 percent or $1.2 million of Omni that was owned by Lewex Inc. was sold to Cairn Energy USA. Harold Levin had been a director of Omni, and the 1992 Lewex Inc. certificate of dissolution listed Leslie Wexner as President and Jeffrey Epstein as Vice President.

In addition to Lewex Inc., there are several other previously unreported Wexner companies where Epstein’s name appeared as an officer on dissolution documents. Many of these companies, like Lewex, had previously listed Harold Levin in an officer or director role—before Epstein pushed Levin out.

One of these companies, PFI Leasing, was incorporated in 1983 and dissolved in 1990. Like Omni, PFI Leasing is mentioned in the Shapiro homicide memo.

Several other companies that are not linked to the Shapiro investigation list Epstein as an officer in dissolution filings (many not previously reported) and show Epstein’s role in managing many of Wexner’s prior business deals:

- Park Properties — dissolved Dec. 22, 1992

- Rocky Fork Development Corp. — dissolved Dec. 22, 1992

- City Centre Investment Corp — dissolved Dec. 28, 1994

- Cherry Bottom Properties — dissolved Dec. 28, 1998 (Cherry Bottom Investors merged w/Cherry Bottom Properties Aug. 30, 1990)

- Wexner Investment Company — dissolved Dec. 28, 1994 (note: Epstein’s name is not on the dissolution document but per this New York Times article Epstein was president in 1991).

- West First Plaza, Inc.-- dissolved 22 Dec 1992

- C-Wren Investment Corp - dissolved 30 Dec 1993

The Lewex Inc., which was later renamed Parkview Financial, and dissolved in 1990, was on real estate transactions for a property next door to Epstein’s New York City mansion at 9 East 71st Street and another property in Queens, New York.

Daily Beast reporter Will Bredderman reported in Crain’s in 2019 that Epstein’s name appeared on records for the neighboring property at 11 East 71st Street. Epstein was listed as “vice president of Sam Conversion Corp. and a trustee of the 11 East 71st Street Trust.” Sam Conversion Corp. purchased the property in 1988.

New York City ACRIS real estate records show that Parkview Financial (formerly Lewex) assumed the mortgage in 1988 with the filing signed by Harold Levin. In 1996 the property was sold to Guido Goldman, the founder of the German Marshall Fund, Harvard professor, former protege of Henry Kissinger, and trustee of several Bronfman family trusts. Goldman was also an alumnus of the Birch Wathen School, which had previously owned Epstein’s property at 9 East 71st Street.

ACRIS records for 11 East 71st Street, block 1386 Lot 12

ACRIS

Parkview Financial Inc. was also listed on property records for a building in Queens purchased in 1987.

Schwartz, the son of Shapiro’s old law partner, maintained that the family firm never—to his knowledge—created tax shelters, and even asserted that Omni belonged to a different client. He insisted that his father, not Shapiro, handled all of the office’s business with Wexner and The Limited.

Like several other individuals interviewed for this piece, Schwartz was dismissive of the Columbus police department’s initial investigation and subsequent memo.

“The Columbus P.D. was covering its ass for being a bunch of lazy stupid good-for-nothings,” he said.

The department did not provide comment for this piece despite repeated requests from The Daily Beast.

The Arthur Shapiro murder case remains unsolved and there are no known calls to reopen the investigation. The prime suspect, Berry Kessler, took his secrets to the grave and Shapiro’s name might otherwise have been lost to history, were it not for the FBI’s investigation into Jeffrey Epstein’s butler.

There are still many unanswered questions about how Epstein was able to take such a huge role in Leslie Wexner’s life and business ventures—and what exactly the duo were up to in the early years of their partnership.

Indeed, Epstein’s activities during the 1990s remain a mystery. Some of them may be answered by looking back at the Shapiro homicide investigation—and what it reveals about Wexner’s business in the years before Epstein inserted himself into their affairs.