Hurricane Joaquin has been yet another example of the complexity of predicting a hurricane’s path and strength. Lives, livelihoods, and wider economic costs make such forecasting a high-stakes endeavor, but hurricanes remain harder to predict than the land-based weather systems that track across continents producing rain, snow, wind, and severe weather.

While both systems consist of spinning centers of low pressure, according to the Kerry Emanuel, professor of atmospheric science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, hurricanes and land-based systems “have completely different physics.” Evaporation of ocean water fuels hurricanes, while land-based low-pressure systems are driven by horizontal temperature changes over land. The strong winds and heavy rains of a hurricane cover a path that is usually 100 miles or so across, and they can change in less than a day; ordinary low-pressure systems can be thousands of miles across and only change over several days, said Emanuel.

These physical differences make accurate forecasting more difficult for hurricanes. “If a forecast of where a hurricane will be in three days is off by 100 miles, it will make the difference between a particular place receiving high winds and heavy rains, or having a nice sunny day,” said Emanuel. “If the forecast of a [land-based] low-pressure system is off by 100 miles, it may make little difference to the weather in particular places.”

Another issue is the data on which forecasts are based. Forecasters use observations to initiate computer models, so the more accurate the initial data, the more accurate the final forecasts. David Stensrud, chair of the department of meteorology at Pennsylvania State University, said there is a kind of data inequality between the continental systems and the tropical areas where hurricanes originate. “Over land, we have much more data. For systems tracking across the U.S. we can get good observations from a variety of sources, including weather stations, satellite data, weather balloons and even commercial airplanes with weather instruments. In tropical areas, especially over water, we don’t have as many observations. And, many of them are only from satellites, which tend to be less precise compared to land-based data.”

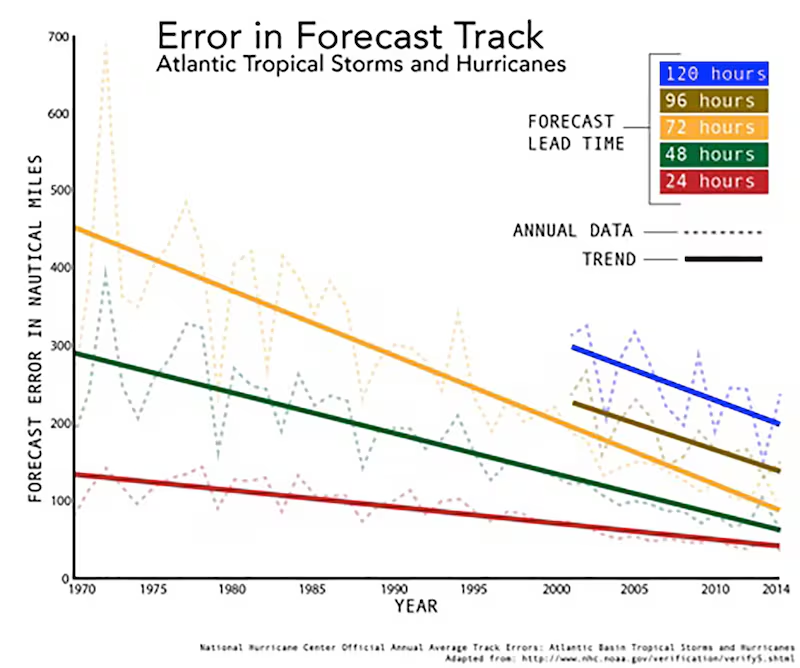

Nonetheless, hurricane forecasts have come a long way in the last 40 years. The graph below shows how the accuracy of Atlantic hurricanes’ forecasted track (but not strength) has changed since 1970. By this measure, our five-day forecasts are now as accurate as our three-day forecasts were in the early 1980s. And as forecasts have improved, so have the public’s expectations.

“The debate today is over whether there will be a U.S. landfall now in five or more days’ time or not; 30 years ago there would have been no point in even having that discussion,” says Adam Sobel, an atmospheric scientist at Columbia University and director of its Initiative on Extreme Weather and Climate, in a recent blog.

Sobel also explains how forecasters look at a variety of weather models and use their best judgment to predict how a storm will unfold. When forecasters relay their predictions, they do so with varying explanations of how they arrived at them and what their uncertainty is. For ease of public understanding, the uncertainty is often not fully explained, though Sobel makes the point that the uncertainty information is there for those who look for it.

But, of course, many people can’t dedicate the time to delving through websites to find and interpret this technical information. They rely on the main messages and graphics put out by the National Hurricane Center (NHC), the Weather Channel, and their local weather stations.

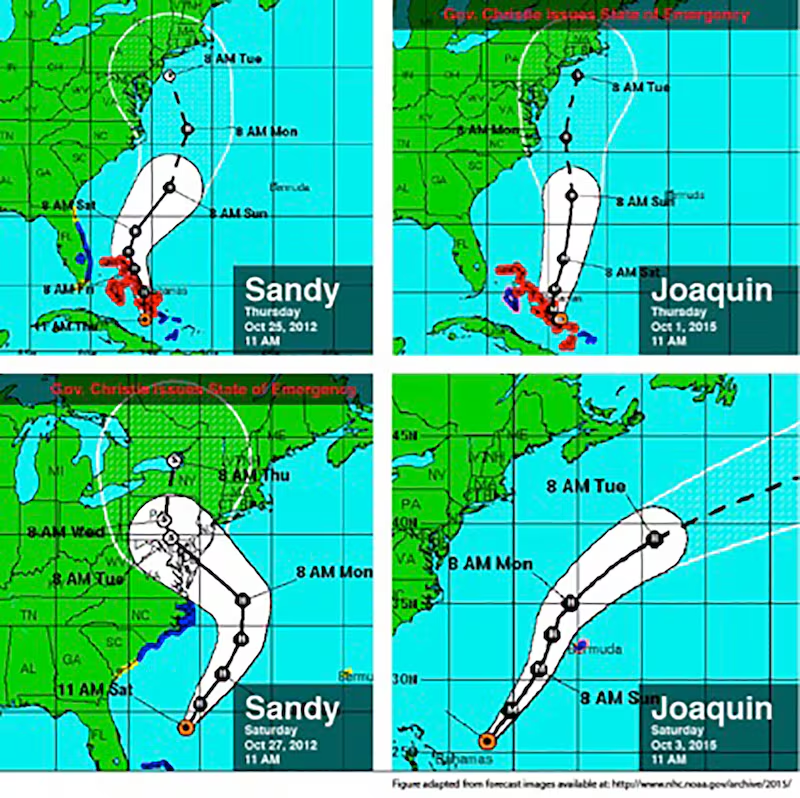

In following up with Sobel on this point, he gave the example of the “cone forecasts” put out by the NHC (see image with Sandy and Joaquin forecasts at about three and five days out). The line in the middle of the cone is the forecasted track, with the cone around it representing uncertainty. The cone, however, does not represent uncertainty specific to that storm. Rather, it’s based on the accuracy of the NHC’s previous forecasts. The specific uncertainty for the storm comes from how differently the various weather models are forecasting it.

If most models agree about the storm’s future, the certainty may actually be higher than what’s portrayed by the cone. “But for Joaquin,” said Sobel, “the models were all over the place. Some models were predicting it landing in the Carolinas, some the Northeast U.S., and some out to sea. They went with the track down the middle, but the cone underestimated the actual uncertainty.”

The National Hurricane Center is aware of the shortcomings in communicating uncertainty. In a blog post following Tropical Storm Erika earlier this season, James Franklin, branch chief for the NHC Hurricane Specialist Unit, said, “We’re thinking about ways we can improve the visibility of our key messages, particularly those that will help users better understand forecast uncertainty…We’re also looking at whether the size of the cone should change as our confidence in a forecast changes.”

In an email to The Daily Beast, Dennis Feltgen, spokesperson for the NHC, said they did include clearly labeled key messages for Joaquin in their public advisories. They also created an image version of the key messages that they shared on social media. “The feedback that we have received from the media, emergency management and the public has been overwhelmingly positive,” he said. This is the first time they have presented this kind of specially-labeled key messaging, and Feltgen says they will continue to do so.

Before it was clear Joaquin was headed out to sea, the storm was being compared (and contrasted) to Hurricane Sandy. Looking at the forecasts of storms reveals a couple of interesting things. First, about five days ahead of their predicted landfall, the storms were both located in the southern Bahamas and had similar forecasts of approaching the New York metro area on the following Tuesday. But, two days later, Sandy was still on a similar track while Joaquin was now predicted to turn eastward and not make landfall. New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie declared a state of emergency when Joaquin was still five days away from predicted landfall. For Sandy, he issued one with three days of warning.

Coastal flooding was predicted regardless of Joaquin’s track, but Sobel questions whether those impacts alone would have been enough to issue a state of emergency and suggests Christie’s action may have been pre-emptive. The timing of these issuances brings up questions surrounding the psychological, decision-making and political implications of forecasts. Did Christie issue one earlier for Joaquin because of his experience with Sandy? Would Christie’s actions have been different if he wasn’t running for president? How do government officials weigh the cost, both in tangible resources and public opinion, of preventive action versus reactive measures?

Of course, decision-makers usually have resources beyond the public statements of the National Weather Service, so the uncertainty has a better chance of being communicated. “But even if they do understand the uncertainty, how they respond to it is another thing entirely,” said Sobel. “There are no simple rules for how to do this. If there’s a forecast for the possibility of an extreme event, and the actions that you need to take to mitigate that event are expensive—well, we shouldn’t envy the people who have to make those decisions.”

On the bright side, Stensrud added that governments and businesses are able to use forecasts more and more to make decisions like whether to close airports, subways, and schools. “Twenty years ago they would have waited for the day of the event and reacted as the event was ongoing, and now they’re doing it proactively because of improvements in the accuracy of forecasts,” he said.