With the Omicron variant disrupting schools and putting state and local governments nationwide on its heels once again, some lawmakers are talking about another round of pandemic relief. But before that discussion goes anywhere, Washington has a question to answer: Whatever happened to the trillions of dollars in pandemic relief that Congress already approved?

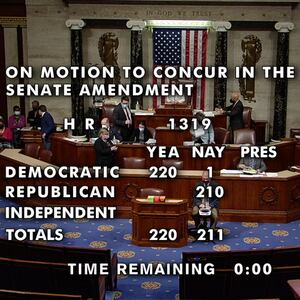

In a Sunday column in The New York Times, liberal pundit Ezra Klein noted that the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, passed in March 2021, included tens of billions of dollars for expanding testing capacity and helping schools make their learning environments safer—two focal points of public anger at the moment.

“Where did that money go?” Klein asked.

In many areas, the answer is straightforward enough: nowhere.

According to experts tracking federal COVID spending, as much as $800 billion of the roughly $6 trillion that has been approved by Congress in the last two years for the pandemic is currently unspent.

The biggest chunk of that total, by far, comes from the American Rescue Plan. That legislation included billions of dollars to directly counter the virus through vaccine distribution and testing. But the majority of the cash went toward broader relief measures like state and local government aid, renters’ assistance, and support for K-12 schools.

Nearly a year after that legislation passed, however, the vast majority of the almost $200 billion allocated to K-12 schools has not been spent. The same goes for half of the $195 billion sent out to state governments. And most city and county governments have not spent much of the $130 billion they collectively received, either.

In some cases, there are understandable reasons behind the tight purse strings. Federal government agencies took time to develop specific rules for what the money could and could not be used for. Beyond that, many state and local governments had to wait to incorporate the funds into their long-term budget plans.

In other cases, though, the reasons are more frustrating.

By the end of 2021, for example, millions of struggling renters who were supposed to get help from an emergency federal rental assistance program still hadn’t gotten any, according to CNN. Fifteen states had distributed less than one-fifth of the money they received from Washington to help renters.

To critics, the trove of unspent COVID cash is an indictment of how lawmakers structured relief bills—particularly the Democrat-written American Rescue Plan—and how agencies implemented the provisions.

“The money was not distributed to state governments, businesses or families that were most in need, which is why so many of them are struggling to spend it,” said Brian Riedl, an economics expert at the conservative Manhattan Institute and a Daily Beast contributor. “They anticipated who might be in need as opposed to those who were.”

Others argue that Washington’s pandemic relief efforts have worked. It’s just that the unspent COVID cash may be evidence that the cost of those efforts was unnecessarily high, said Marc Goldwein, senior policy director at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget think tank.

“It’d be hard to consider this anything but a success overall, given we accomplished everything we set out to,” Goldwein said. “The issue is we spent, on net, $5 trillion-plus to do it. We didn’t do it efficiently, and money went to where it didn’t belong, and we’re seeing consequences of that in the form of higher inflation and other labor force issues.”

While watchdogs and policy wonks are scrutinizing the unspent COVID funds, lawmakers on Capitol Hill are talking about putting together yet another pandemic relief package to respond to the Omicron variant.

In the Senate, a bipartisan duo have sketched out a $68 billion bill focusing on targeted relief to struggling sectors of the economy, according to The Washington Post. House Democrats, meanwhile, are increasingly backing efforts to respond directly to the virus with funding for testing measures and mask distribution—among other things.

There’s broad agreement that legislation with some or all of these measures would be helpful right now. But to experts like Goldwein, tapping into the nearly $1 trillion in unspent pandemic funds would go a long way to meeting current needs. State and local governments, he argued, “have the resources to be addressing this stage of the pandemic—to make sure people are getting masks and tests, for individual financial relief.”

Still, outside experts who have been tracking specific tranches of COVID relief largely are not concerned with the slow pace of spending. Most believe the relief bills had two purposes. One was to provide a short-term lifeline to the neediest and to meet the most urgent needs of the pandemic. The other was to lay out long-term investments to rebuild from the pandemic and, ideally, have the country come back stronger.

“Equitable recovery isn't just about giving health care to everyone who got sick,” said Ed Lazere, a senior fellow at the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, a liberal think tank. “It’s about repairing systems that weren’t that strong, like mental health and food assistance.”

The American Rescue Plan, spearheaded by President Joe Biden and supported only by congressional Democrats, was structured with this idea in mind. The dollars authorized by the legislation can be spent through 2026.

That timeline is especially important for state and local governments, perennially underfunded, who got a windfall from the Rescue Plan. Republicans have criticized Democratic relief efforts as a giveaway to governments that, despite gloomy predictions at the start of the pandemic, have weathered things just fine since summer 2020.

Alan Berube, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, has been tracking COVID relief to city and county governments. He said only “some” of the $130 billion these localities received has been put to use so far, which is understandable given the nature of the recipients. Local government, he said, “operates at the speed of trust, not just the speed of cutting a check.”

Berube also argued there is a wide array of possible long-term uses for this funding that supports the mission of recovering from COVID. “Of course we want to solve for the impact of the immediate crisis,” he said. “But we also want to help cities, counties, states, solve for what had been a long period of underinvestment brought on by state budget cuts that trickled down to cities and counties.”

The situation with K-12 schools is especially illustrative of the complex dynamics at play with COVID relief. The Omicron outbreak has punished the education system; teachers have protested unsafe conditions—some districts lack mask supply and other basic necessities—and school districts in many states are still waiting on resources to expand their testing capacity.

The roughly $190 billion for K-12 schools in the Rescue Plan—roughly $2,800 per U.S. student on average—has largely not been spent, said Anne Hyslop, director of policy development at All4Ed, a nonprofit education advocacy group. She said that few in the education world expected the Rescue Plan’s funds to hit quickly, and emphasized that funds from the legislation can be used through the 2025 school year.

In prior COVID relief efforts, like the $2.3 trillion CARES Act of April 2020, the focus was on the “immediate short-term needs of schools,” Hyslop said. “When you get to ARP, the thinking shifted to long-term needs that students and school districts would be facing.”

That’s necessary, Hyslop added, given the growing evidence that educators will have to work overtime in coming years to make up for how far many students fell behind during two years of remote or inconsistent learning.

“That’s not a process that’s going to take a single school year,” she said. “That’s going to take several school years.”

Some observers, like CRFB’s Goldwein, have concerns that this K-12 funding has incentivized some states and districts to pad their budgets long-term rather than heavily invest in helping schools weather the Omicron wave—or whatever may come next.

In any case, the dollars in the Rescue Plan and other COVID response bills might represent the last tranche of real pandemic relief that governments, schools, businesses, and the public will get.

Even though lawmakers have pushed for modest response bills this new year—Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) indicated on Wednesday that relief funds could come as part of the delayed annual spending bill—other top Democrats have not exactly warmed to the idea of pushing out more aid. White House officials are reportedly preparing to request money from Congress, but the prospect of a broad relief package similar to past ones is distant.

Given that state of play in Washington, and the consistently unpredictable nature of the pandemic, experts say it’s hardly an issue that hundreds of billions in COVID relief remain.

“The notion that we’re out of the woods, and that states won’t have any economic woes this year because of the pandemic,” Lazere said, “who knows how long it’s really going to take to recover?”