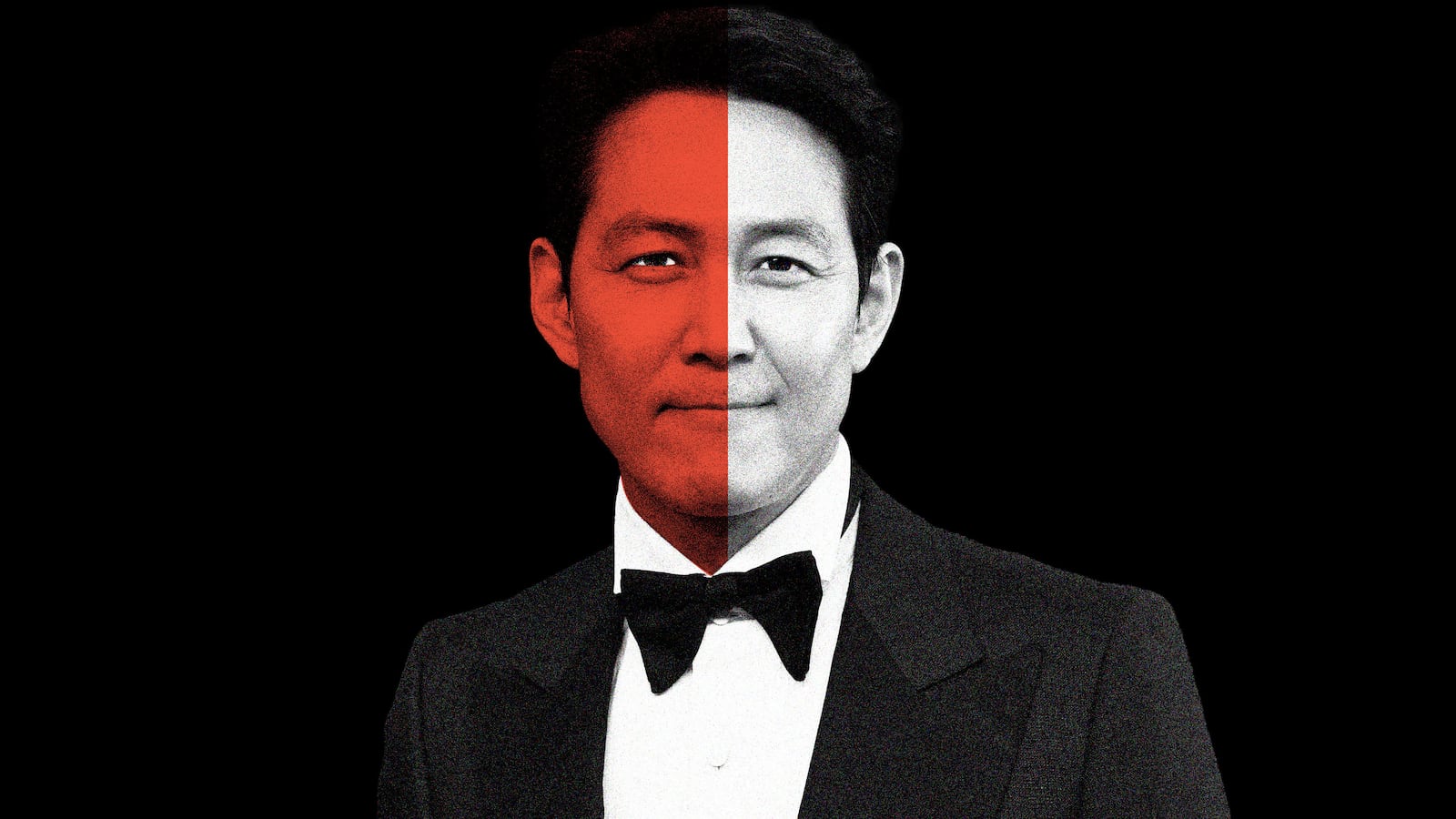

Lee Jung-jae took home Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series at Monday night’s Emmys for his role in Netflix’s global smash Squid Game, besting the likes of Better Call Saul’s Bob Odenkirk and Succession’s Jeremy Strong and Brian Cox. In the process, he made history as the first Asian man to win the Lead Actor Emmy.

For his role as Seong Gi-hun, a divorced father and deep-in-debt gambler who’s lured into a deadly game of survival with a huge cash prize, Lee has emerged as the breakout star of Squid Game, which still ranks as Netflix’s most-watched series ever (even though he’s had a storied career in Korea for decades, including Grand Bell and Baeksang awards). Lee is arguably the most recognizable Korean actor in the world right now—and his star will rise even higher after landing a leading role in The Acolyte, an upcoming Star Wars show.

But if we’re going to use Lee to celebrate everything that’s great and different about Korean TV, we also need to acknowledge everything else he represents—including how, similar to the West, male Korean stars enjoy the benefits of an industry that bends over backward to protect and preserve their image.

In 1999, Lee was detained by Gangnam Police for driving under the influence and causing a collision with another driver, a 23-year-old woman. His blood alcohol content was 0.22 percent (in South Korea, the limit is 0.05 percent). Lee refuted the charge, claiming his manager was driving. Three years later, he was charged with the same offense.

That same year, in 1999, he and a friend drunkenly attacked another man and were charged with assault. He was charged with assault again the following year after he allegedly dragged a 22-year-old woman from a nightclub in Busan and kicked her, causing injuries that required two weeks of recovery in the hospital.

Fast-forward to 2013 where, in an interview with Vogue Korea, Lee appeared to out his friend and prominent stylist, Woo Jong-wan, soon after his suicide. Before he died, Lee claimed, “I said to [him], ‘You should stop being gay. Haven’t you been that way enough?’” He went on to describe Woo’s homosexuality as an “inconvenience.” The quotes were subsequently pulled from online versions of the interview.

Fans argue that it was so long ago that it doesn’t matter. Indeed, we should acknowledge and encourage growth if we see it. But we haven’t. Lee hasn’t wrestled with the allegations in interviews or shared any information about steps he’s taken to rehabilitate himself; instead, they’ve been all but swept under the rug. Nor do we know if this is the sum of Lee’s past. We can only judge what we see and, as you can probably tell from those quotes disappearing, what we see of Korean stars is heavily curated—by the film and TV industry, by the media, and by fans.

This isn’t entirely unique to Korea. It is, in many ways, universal to modern-day celebrities. But whereas this kind of reputational smoothing in the West often centers on humanizing celebs, in Korea it’s about shoring up an unrealistic, aspirational ideal that cannot be compromised.

After all, when we recognize public figures as human beings, it’s easier to attach their transgressions onto them. In Korea, red flags are carefully hidden under layers of branding that can be impossible to dislodge—at least if you’re a man.

The leeway Lee has enjoyed over these reports has been compared to Johnny Depp. It’s the same kind of entrenched, manufactured image that allows Depp’s fans to completely dismiss overwhelming evidence of his abuses—or even sanction it.

So, too, do Lee’s fans casually ignore reports of his assaults and homophobia. Who cares? they ask, far more interested with the image they have helped construct over the years. This kind of violence simply doesn’t gel with the Lee Jung-jae they’ve convinced themselves they know, driven by the sprawling tendrils of misogyny that protect men in the film and TV industry across the globe.

The same misogyny that insulates Lee from these reports means that, in Korea, men can survive accusations of sexual harassment and assault while rumors of bullying can derail Seo Ye-ji’s career, or Song Ji-a wearing fake designer clothes causes her to be branded dishonest and chased off social media.

This same misogyny allows Depp to continue to gather endorsements and acting gigs while Amber Heard may never work in the industry again—and other men use her as a way to vilify their own accusers.

It’s easy for Western audiences to forget all of this while watching Korean television, losing oneself in a culture about which so many of us know precious little. But if we’re going to engage with Korean TV (and we should, it’s incredible) we need to understand that what we’re seeing is a carefully constructed fabrication of what Korea should look like, where anything that could be regarded as a blemish is censored out of shows. And its stars are similarly insulated from ideas that run contrary to Korean ideals—for instance, that one of Korea’s biggest stars might not be as clean-cut as managers, assistants, and minders want him to appear.

I want people to fall in love with Korean TV—it’s a rewarding love affair—and welcome the success of its stars in a global market. But we also must understand that beneath ostensibly feel-good stories of men like Lee Jung-jae achieving global stardom, there can be just as much darkness as there is in places like Hollywood.