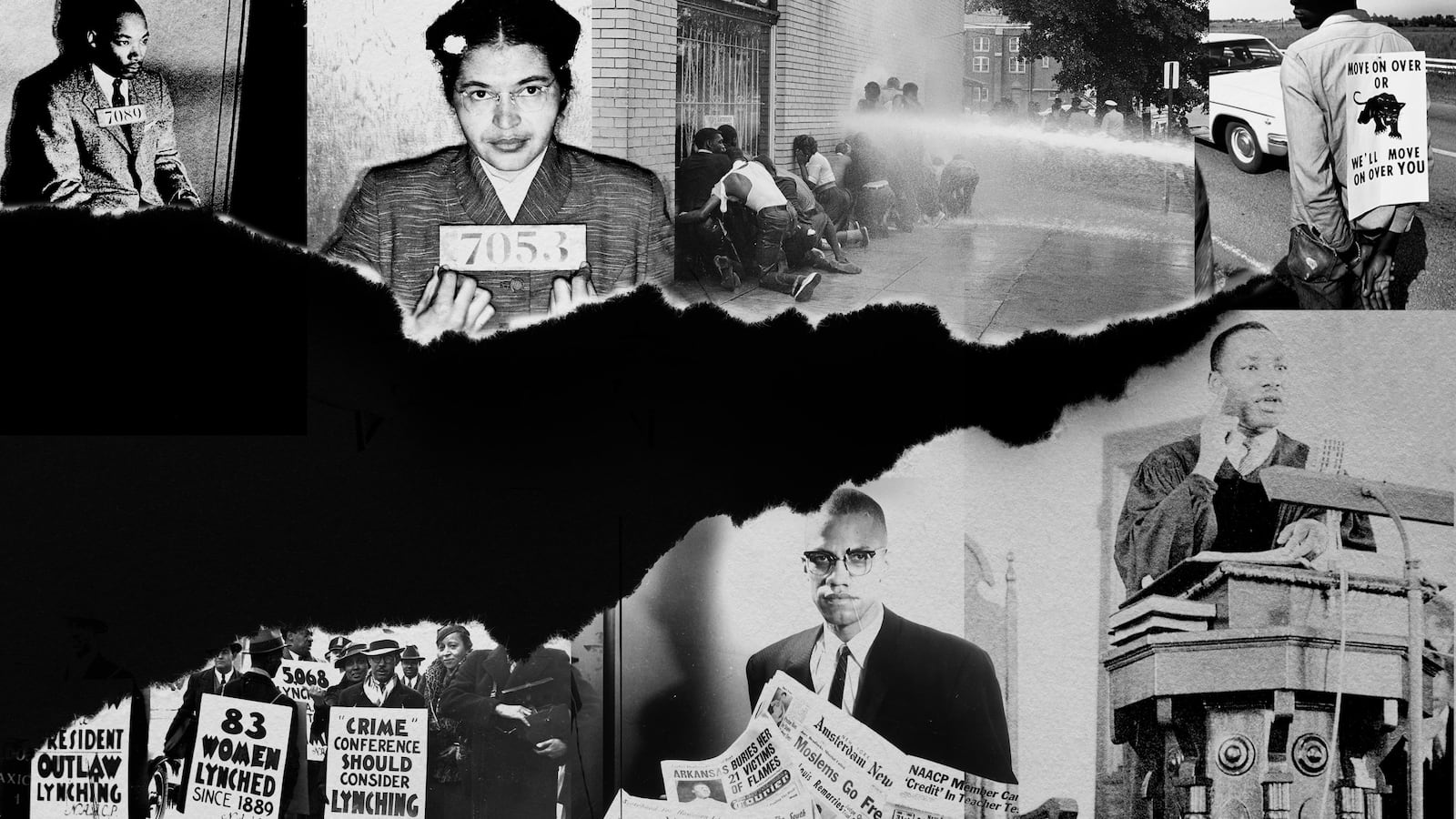

Conventional history has often confined African-Americans to antebellum slavery and the civil rights movement, compacting hundreds of years and millions of lives into the stories of Frederick Douglass, Rosa Parks, and Martin Luther King Jr. The history of black America has been relegated to Black History Month, as though the history of black people in this country is separate and distinct from American history. Black History Month was created to make visible the often-overlooked presence of African-Americans in U.S. history and has served an important function. However, the persistence of segregated histories masks a critical truth: there is no American history without African-American history.

Up until the early 19th century, most Americans arrived in the New World as slaves. Africans preceded the English in the Americas by a century and arrived in numbers that far exceeded European migrants. In the Americas at large, involuntary African immigrants outnumbered European arrivals by a factor of 4 to 1 until 1820.

While American history was founded in slavery, it cannot be reduced to slavery. People of African descent were among the first explorers, settlers, and defenders of this nation. In 1524 Spain commissioned the Afro-Portuguese navigator Esteban Gomez to explore the Hudson Valley; in 1528 the Afro-Spaniard Esteban Dorantes traversed from Florida to Mexico. The first permanent transatlantic settlers in what became the United States were enslaved Africans who fled a failed Spanish colony in Georgia in 1526, 81 years before Jamestown’s 1607 founding. Baptismal records from 1606 announce the birth of an Afro-American child in Spanish St. Augustine, and the Spanish colonist Isabel de Olvera, the daughter of African and Amerindian parents, accompanied the Oñate expedition from Mexico City to Santa Fe in the early 1600s, which we know because she made an affidavit attesting to her free status.

Individuals of African descent were integral to the Spanish colonization of North America from Florida to California (in 1781, Los Angeles was founded by a largely mixed-race settlement governed by an Afro-Spanish soldier). Afro-Americans were crucial to the establishment of Dutch, French, and British North America. New York City was founded in 1613 by the Afro-Dominican sailor and translator Jan Rodriquez, who was hired by the Dutch to collaborate in their trading missions with New York’s Native residents, with whom Rodriguez settled and married. Similarly, Chicago’s first non-Native settler was Jean Point du Sable, an Afro-Haitian trader who established a business and a family with a local woman. Africans arrived in Jamestown in 1619—among them was Anthony Johnson, a former servant who managed to amass property, start a family, and lay claim to his servant John Casor for life. The 1655 case in which Casor argued that he had completed his term of service and was free to contract with Johnson’s white neighbor was lost; Johnson was awarded his legal fees, Casor’s lifetime service, and, in retrospect, the perverse distinction of being among the country’s first legal slave owners.

In New York in 1644, enslaved petitioners argued for their freedom, which they were granted, along with some 130 acres around what is today Washington Square Park. (The son of one of these former slaves, Lucas Santomee, went on to earn a medical degree and license as a physician in the 1660s.) In addition to the pervasive acts of individual resistance that ranged from slaves liberating themselves through flight to petitioning legislatures and arguing in courts, enslaved Americans rose up en masse for freedom in Bacon’s Rebellion (1676), the Stono Rebellion (1739), the New Orleans Slave Revolt (1811), and the Second Seminole War (1835-1842) as well as during the American Revolution, the War of 1812, and the Civil War.

African-Americans served as soldiers in every single U.S. military engagement. Many thousands fought with the patriots during the American Revolution, along with Afro-Haitians in Georgia and Afro-Cubans and Afro-Mexicans who fought against the British in Florida. African-Americans and Afro-Haitians fought for the United States again during the War of 1812. During the Civil War, hundreds of thousands of enslaved Americans fled plantations to fight for the freedom of others. (Looking at South Carolina’s declaration of secession, one could argue that it was enslaved Americans freeing themselves—and Northerners failing to return them—that instigated the war.) Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation as a means to officially enlist the massive tide of enslaved Americans fighting for the nation, whose service, Lincoln ultimately recognized, was crucial to preserving the Union.

In the United States, we have been conditioned to think of black people as a minority, but throughout the 19th century nearly half of all Southerners were black, and today African-Americans comprise substantial populations of major cities like New York, L.A., Chicago, Philadelphia, and Miami and majorities in many cities, including Cleveland, Detroit, Richmond, Atlanta, Birmingham, Memphis, New Orleans, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C.

We will not understand American history until we understand how it is inextricably entwined with African-American history. The history of slavery is every American’s history because it formed our country and continues to shape our economic, political, social, and demographic landscape. However, the continuous struggle against slavery—and slavery’s ubiquitous fallout—and toward democracy is a powerful tradition, largely generated by Americans of African descent, which we can celebrate and build upon. Teaching our children that black history belongs to one abbreviated month when the faces of a few representative figures appear on bulletin boards does both the past and the future a grave disservice. Black history has always been American history, from the Age of Exploration through today. We must recognize our past as an integrated narrative in order to understand ourselves as Americans, with a shared history, a shared present, and a shared future.

Christina Proenza-Coles has a dual doctorate in sociology and history and is the author of the forthcoming book American Founders: How People of African Descent Established Freedom in the New World (NewSouth Books).