Today, most people make it to their late seventies before dying of old age. If you were born in 1880 in the U.S., though, you’d be lucky to see your 40th birthday when you were born. Over the years, our lifespan nearly doubled thanks to science and medicine. But why should we stop there—and what happens if we don’t? For many, that’s a billion-dollar question—literally.

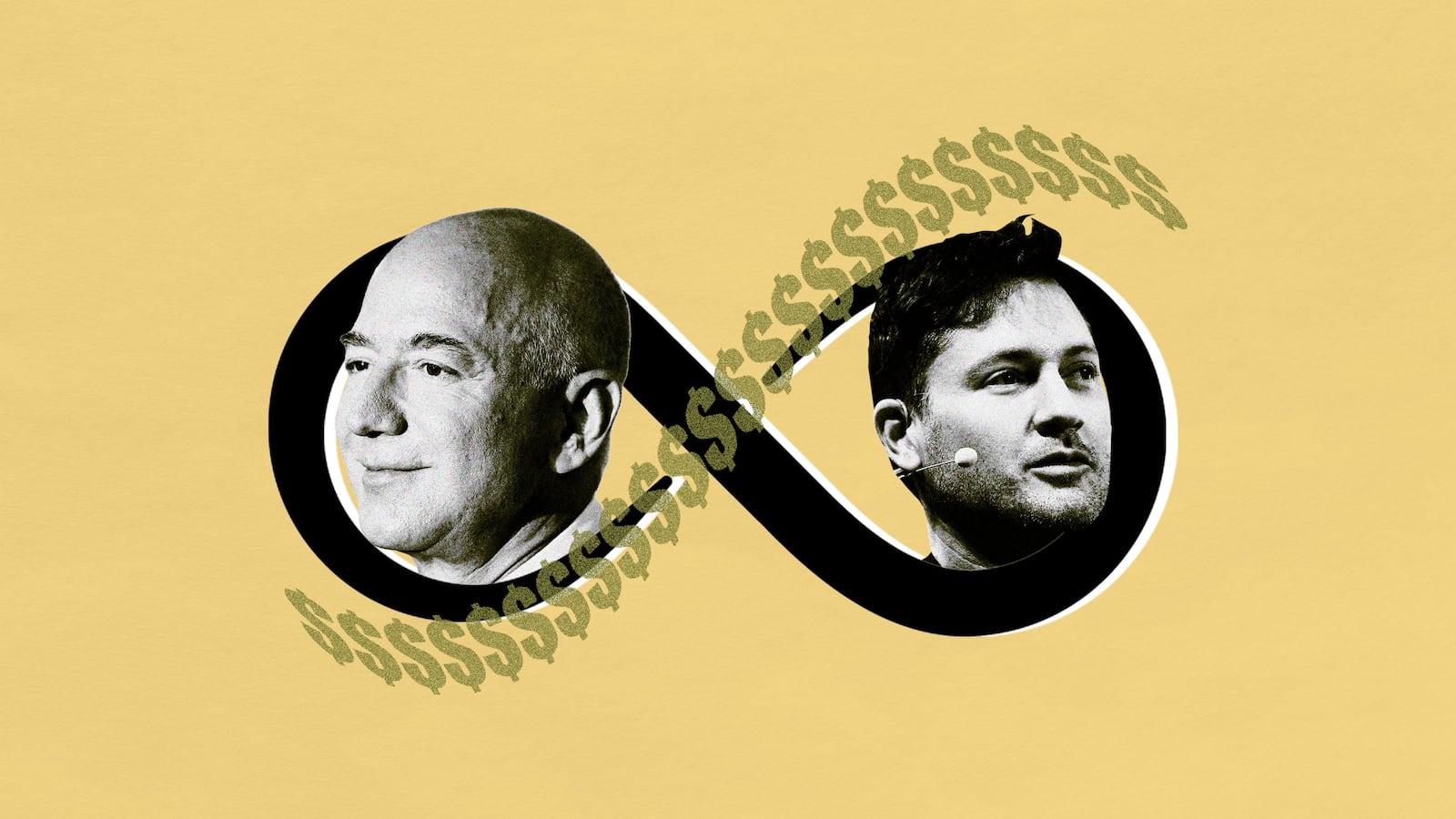

Investment in longevity startups surged to $5.2 billion in 2022, with the market projected to hit $44.2 billion by 2030. Billionaires like Sam Altman and Jeff Besos have been supporting ventures targeting longevity research such as cellular rejuvenation, gene editing, and AI drug discovery.

Take, for example, 46-year-old tech millionaire Bryan Johnson who has recently been making headlines with his extreme anti-aging regimen. He rises at 4:30 a.m., eats all his meals before 11 a.m., and goes to bed at 8:30 p.m., without fail. He told The Daily Beast he subsists on a strict diet of 2,250 calories, where every calorie “has had to fight for his life,” and takes more than 100 supplement pills every day. Johnson claims that this process has allowed him to become the “most measured person in human history”.

“I want to be the personal embodiment of this idea of ‘Don’t die’ and to build an algorithm that takes better care of me that I can myself,” he said.

Experimental technologies involving genomics, regenerative medicine, nanotechnology, and artificial intelligence are making their way from the fringes to the mainstream with longevity researchers and Silicon Valley types like Johnson pushing for a life extended by at least a couple of decades. In doing so, the wealthy and powerful have offered themselves—and their wallets—up as guinea pigs, with the idea being that the fountain of youth will eventually trickle down to the point where it is available to all as has ostensibly been the pattern with other technologies.

“My endeavor is to basically figure out how to not die,” Johnson, who thinks of himself as a ‘professional rejuvenation athlete’, explained. “People hear this and they jump to all these conclusions. None of it’s accurate, I’m just playing the same game everyone’s playing: Don’t die.”

Bryan Johnson on stage of the Web Summit in Lisbon on November 7, 2017. Johnson is known for his numerous unorthodox treatments and practices that he claims is making him younger including a strict diet and sleep schedule, penis injections, and swapping blood with his son.

PATRICIA DE MELO MOREIRA / Getty ImagesIt may sound obvious that most causes of death are age-related. In order to live longer, it is simply a matter of treating or preventing these age-related diseases. One option, as Johnson is attempting, is to simply not age.

“At the moment, when you were born a long time ago, you have no way to escape going downhill, both mentally and physically,” biomedical gerontologist Aubrey de Grey told The Daily Beast. No one looks forward to this mental and physical decline, so this is where researchers like de Grey step in.

Common sense says if you live a healthy lifestyle you stand a stronger chance of living longer. For de Grey, life extension is the next logical step after living such a lifestyle. “It’s simply about developing new medicines that can achieve this goal to a larger degree than what we can do with today’s technology, whether that be lifestyle, diet, or exercise.”

In the same way that medicines, treatments, and the simple concepts of hygiene and sanitation have doubled our life expectancy from 40 to 80 or more, de Grey explains. Science is now beginning to address “the next thing that’s killing people who are no longer dying of that first thing.”

Faced with the idea that someday soon we will have the option to slow down or reverse aging, one question continually crops up: Do we even want this? It only takes a look at the headlines and research generated over the past few decades to deduce that the field of life extension has been complicated and controversial. On top of an already aging population, some question if longer lives could threaten our social and economic systems. Others wonder if the quality of life is more important than the quantity.

For de Grey, the answer to the first question is obvious: Yes. “The people who ask that question are just as keen to go to the hospital when they get cancer as anyone else,” he explained. “They don’t have to have a reason; they just don’t want to get sick any more than anybody else does.”

Aging is bad for our health, but up until now we haven’t been able to do much about it. As a result, people have found ways to cope psychologically, de Grey explained. “One way is to somehow trick yourself into thinking that it’s some kind of blessing in disguise so that then if we didn’t have aging, we’d have even worse problems.”

Some argue that aging is a natural part of life and something we should embrace rather than run from. “A lot of people will persuade themselves that aging is just not like other medical problems,” de Grey said. “That it's kind of woven into the fabric of the universe and it’s inevitable, universal, and natural.”

He added, “That’s also nonsense.”

What is natural is not fixed. Instead, it is determined by our environments, John K. Davis, a philosophy professor and bioethicist at California State University, told The Daily Beast. “We evolved so that we don’t maintain ourselves any longer than our environment lets us,” he added. “We’re now living in a human-made environment, so what was natural when we were essentially smart primates is not natural now.”

So, as technology advances and we have the means to live a few extra decades, why wouldn’t we?

Of course, there’s the question of who gets to live longer. Inequality underpins human society, where some people live longer than others simply because they have the means or access to better health care. Some say these inequalities would only get more entrenched if there is a miraculous life-extending medicine or treatment on the market.

“If some people don’t get access to it, life’s gonna be much tougher for them,” Davis said. “It’d be much harder for them to accept death. There’s a kind of harm involved there.”

For example, Johnson reportedly spends $2 million a year on his team of 30 doctors and cutting-edge technologies. Meanwhile, the likes of Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, and Sam Altman are also pouring their billions into longevity research, while also having access to higher standards of medical care than the rest of us. It seems unfair for billionaires in Silicon Valley to celebrate their 150th birthdays while the majority typically reach 70 or 80 before biting the dust.

However, longevity proponents argue that it’s not morally right to deny access for some just because there can’t be access for all. Health and wellness isn’t a zero-sum game. “We don’t deny people heart transplants because there aren’t enough hearts to go around,” Davis said. “It’s not a general principle of justice that we achieve equality by leveling down.”

Then there’s the question of should we be spending money solving aging in a world where many people lack access to basic health care. To that, Davis asks, “How confident would you be that, by inhibiting life extension, those other needs would in fact be met?”

“No one comes to death as the solution for these problems,” Johnson explained. “We try to figure out other ways to solve problems because we value life and so these other things are just tangents to the real questions.”

However, one common concern that doesn’t have such a simple answer is overpopulation—which can be exacerbated if people have more time to have babies, and when people stick around longer. It’s something that Davis admits is a big challenge when it comes to a potential reality where people live much longer. “It’s really tough to solve that problem, because it’s simple arithmetic,” Davis explained. “There’s no drug that's going to fix that.”

Of course, all technologies have their upsides and downsides. When dealing with the negatives, time is on our side. Despite the challenges that life extension presents, history suggests that society would adjust. From the genes of our paleolithic ancestors mutating over time to protect from hazards, to public health advances contributing to the doubling of life expectancy between the 19th and 20th century, humans are quick to adjust. Then there are the potentially positive social consequences to consider when adding an extra few decades onto our lifespans.

“The main impact would be, we wouldn’t be spending trillions of dollars a year keeping people alive because they wouldn’t be getting sick in the first place,” de Grey said. Preventing age-related diseases would lead to a more comfortable old age, making retirement-management simpler due to prolonged work. Moreover, it might end up benefiting younger generations too, outside of helping them live longer.

“I think as people get older, they do become wiser,” Davis added. “We might be more inclined to take an interest in future generations because we think we’re going to be there.”

Living a long and healthy life is not a controversial idea. When it comes down to it, what’s a few decades tacked on to the end? At the moment, our lives and careers are structured around a beginning, a middle, and an end. With longevity research gaining steam, we might see that structure stretch out quite a bit more into something new—and transformative.

“If you’re living indefinitely, maybe it’ll be a different structure,” Davis said. “More like a TV series than a movie.”