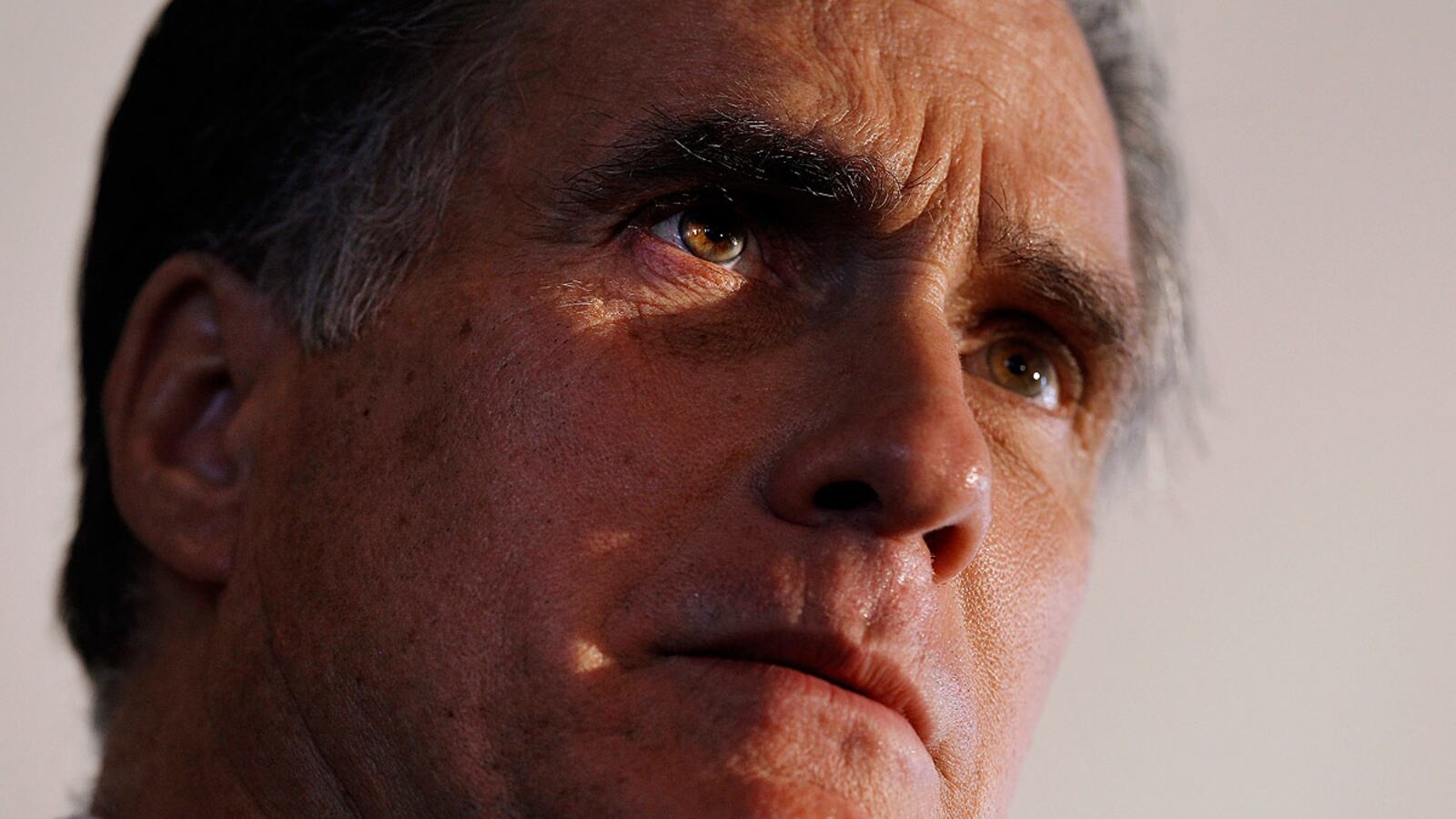

Less than 50 days from the election, it’s still Mitt Romney’s biggest mystery.

He is an exemplary husband and father—the kind of man you would want as a member of your church or would trust to run your business.

So why do so many people find it hard to warm up to Willard?

His “47 percent” comment resonated because it reinforced the negative narrative about Mitt as an out-of-touch member of the superrich with little feeling for policy, politics or people—a million miles away from W’s “compassionate conservative” mantra. He comes across as an awkward mix of Barry Goldwater, Richard Nixon and Nelson Rockefeller, without any of the redeeming qualities. And it’s arguable which is worse—whether Romney essentially believes what he said at the $50,000-a-plate fundraiser, or was simply pandering to the well-heeled audience.

At least three Republican Senate nominees—Scott Brown, Linda McMahon, and Dean Heller—quickly distanced themselves from his comments, followed by Ohio Gov. John Kasich and condemnations from a half-dozen high-profile conservative columnists, including Bill Kristol and Peggy Noonan. According to a new Pew Survey, no other presidential candidate’s unfavorable ratings have been as high at this point in a campaign.

His problems are compounded by an open secret in Republican politics—no one who has ever run against Mitt Romney walks away liking the guy.

This feeling about a candidate is not always the case—George W. Bush was acknowledged to be a ‘hail fellow well met’ even by his sometimes brutally vanquished foes. Likewise, John McCain was widely admired for his courage and character, even by rivals who disagreed with him deeply on policy. But with Mitt it’s something different.

It’s telling that during and after the 2008 Republican primary, warm feelings did not abound for Mitt Romney. All the other candidates basically got along, even after the fierce competition. There was a sense of camaraderie that came from the surreality of their situation. But the easy off-camera humor never extended to Mitt. Instead there was stiff formality and a simmering resentment.

“Four years ago, the other candidates couldn’t stand him,” said a longtime Republican operative affiliated with another competing campaign in 2008. “There was just this aloofness to him and an elitism that set the tone. There wasn’t the comradeship that you normally have with candidates—you know, when you get to know each other in the course of the campaign and you kind of like each other and respect each other, no matter how badly you beat the daylights out of each other. Romney hammered every single candidate with negative advertising above and beyond what was needed—and his attitude seemed to be ‘I didn’t say it.’ It was this mysterious ad agency off somewhere.’ His aloofness is just what sort of puts people off.”

Likewise, look at the Republican primary candidates Mitt faced off with this year. Rick Perry still seems to be barely on speaking terms with Romney, even though he’s playing the role of good soldier. Rick Santorum waited almost a month before mouthing his support. Newt Gingrich’s nervous tick is to remind his audience that the contest isn’t between Romney and Reagan, but Romney and Obama. But the bitterness of his primary campaign complaint—"How can somebody run a campaign this dishonest and think he’s going to have any credibility running for president?—still resonates with more authenticity than his endorsement. The only unifying factor is intense opposition to President Obama.

It’s often said that when it comes to presidential nominees, Democrats fall in love and Republicans fall in line. Conservatives have long warned about the inability of Romney to excite the base, but the new Pew Survey quantified this dynamic, showing that “roughly half of Romney’s supporters say they are voting against Obama rather than for the Republican nominee.”

I’ve come to believe this disconnect is rooted in Mitt Romney’s essentially businesslike approach to politics.

Most Republican politicians who came of age in the Reagan Era are Conviction Politicians. They were moved to public service by a deep commitment to a set of principles and policies.

Mitt Romney approaches politics in a more transactional way. He wants to improve the country but he is fundamentally a salesman and in this world view, it would be illogical not to tailor sales to the needs of different audiences. Why would Mitt try to make the same pitch to a Massachusetts electorate as Republican primaries voters? It’s not personal; it’s business.

This businesslike approach to politics also explains Mitt’s willingness to go negative. On the surface, the “death star” approach of burying opponents in an avalanche of negative ads, as Romney did in Iowa and Florida, seems inconsistent with a man of deep morals and religious faith.

But if you believe that politics is essentially a dirty business—a necessary evil to get ahead and eventually do good, then you make a mental division: you render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s. And so going negative is simply the coin of the realm. Honor in politics is misplaced.

The combination of these two factors ends up alienating many of Mitt’s fellow political figures. Those who have run against him feel that he is quick to amplify dishonest attacks—and the sting is more infuriating because it comes with a base alloy of hypocrisy.

It is almost hackneyed to say Romney doesn’t seem to have any core political beliefs, but it’s rooted in his record. He moved left to win the Massachusetts governorship; he moved right to win the Republican nomination; and now to win the presidency, he wants to disappear into a cloud of unoffending generalities whenever possible, running an essentially policy-free campaign before picking Paul Ryan as VP.

His career-long litany of flip-flops, from abortion to gay rights to health-care reform to climate change to the assault weapons ban, only reinforces the point.

One of Romney’s few consistent policy stands has been his tough anti-illegal immigration talk. But on Wednesday, in his Univision interview, he casually abandoned even that by saying, “We're not going to round up people around the country and deport them.”

Either Romney hasn’t listened to his own rhetoric, read his own policy papers, or just can’t resist the impulse to pander to an audience.

All this is difficult to respect, especially for fellow political practitioners, even in his own party.

As a businessman, Mitt Romney compiled an admirable record of success. But his record is government is thin because he treated the Massachusetts governorship as a necessary way station for a presidential run. His core achievement, health-care reform, was disavowed because it is now politically inconvenient. And his claims of managerial competence have been undercut by his disastrously run campaign—but at the end of the day, that is not the staff’s fault: tone comes from the top.

There is an almost slapstick quality to the mishaps at this point, the dozen attempts at rebooting Romney undercut by the candidate’s own comments on the campaign trail. At times, he seems like a Monty Python caricature of a self-consciously noble knight with a killer instinct for self-sabotage and alienating allies, all adding up to the title, Sir Not Very Well-Liked.

Look, I still believe Mitt Romney is a good man deep down. But his dislike of politics, his disregard of policy details, and his plain discomfort with average people ends up looking like a disdain for the democratic process, and that’s a problem if you want to be the president of all Americans. Overriding personal ambition and not being Barack Obama isn’t enough to earn the Oval Office.