The case of the Sarah Lawrence College cult is peak true-crime fodder, to the point where it’s gotten two separate docuseries in the past five months. The version of the story as told by Peacock’s salacious September release Sex, Lies, and the College Cult was especially tantalizing. A bunch of college co-eds fall under a dad’s spell, leading them to move into a one-bedroom apartment with him, have sex with each other, and endure emotional and physical abuse for years.

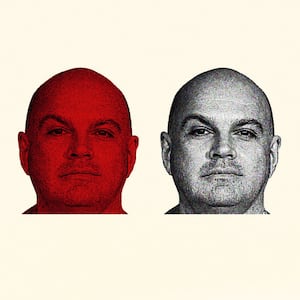

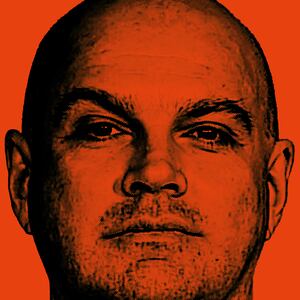

That doc, however, was a tacky reduction of this specific story. Larry Ray, who was recently sentenced to 60 years in prison for sex trafficking, conspiracy, and 13 other charges, preyed upon a specific set of people: twentysomethings dealing with mental health issues; men and women of color butting up against societal pressures of being underprivileged; kids still figuring out their sexuality. Each of the college kids who Ray blackmailed, abused, and brainwashed was particularly susceptible to his manipulation.

Hulu’s new series Stolen Youth: Inside the Cult of Sarah Lawrence is the first version of this lurid yet intoxicating crime story that recognizes this. And that’s most apparent in how Stolen Youth gives the most heartbreaking victims of Ray a human story—allowing them to speak up, on camera, free of their tormentor’s presence and influence.

In the initial reporting on the Larry Ray/Sarah Lawrence case, Felicia Rosario emerged as the most heart-wrenching example of Ray’s psychological damage. In 2010, 27-year-old med school grad Rosario met Ray through her college-age brother Santos; Santos was dating Ray’s daughter Talia when he entered the toxic clique. Ray and Felicia quickly struck up a powerful, emotionally wrought relationship, leading to Felicia ditching her residency program in L.A. to move in with Ray, her brother, and the other kids; Felicia and Santos’ sister Yalitza had also joined by this point.

Felicia’s story stood out among the others for both how much and how long she endured Ray’s abuse. Perhaps it was that she seemingly sacrificed the most by giving up on her dreams to become a psychiatrist that made her such a compelling figure—or perhaps it was the irony that a budding psychiatrist could so swiftly fall for a master manipulator like Ray. Either way, footage of Felicia is the most disturbing to watch of all the tape that Ray recorded over the near-decade he held his captives as psychological prisoners. (Why people like Ray or other recently nabbed cult leader Keith Raniere document their abuses so thoroughly, I’ll never understand.)

For years, Ray taped Felicia screaming on the floor in a clear psychic break; begging for forgiveness for things she did not do; claiming that she had been poisoned, simply because Ray told her she was; and having incessant panic attacks. This footage is all over Stolen Youth, just as it was in Sex, Lies, and the College Cult as well as other reports of the case. Felicia was seen as a symbol of what a cult can do to a promising young woman: render her unstable, leave her disheveled, and make her a shell of her former self.

What director Zach Heinzerling’s Stolen Youth does differently, however, is that it tells the story not from the perspective of a ravenous observer, but from nearly all of Ray’s young victims, letting them recount their own stories of succumbing to such a strange man’s beliefs. The shock of hearing about what Ray made the kids do—sleeping on the floor of a one-bedroom apartment, telling him about every negative thought they’d ever had, letting him convince them that their family members were to blame—is mitigated by the sadness of hearing them tell it. There’s an allowance for empathy here that even the best journalism hasn’t granted the victims; their first-person accounts allow us to directly connect with and understand their unique circumstances.

That Heinzerling was able to interview Felicia, in particular, is a huge win. From a reporting perspective, it’s of course crucial to get as many sides of the story as possible. But Stolen Youth grants Felicia an arc that any docuseries would be lucky to secure. We first meet her shortly after Ray has been arrested, where she and fellow victim Isabella Pollok are living in the cocoon-like New Jersey home Ray ultimately sequestered them in. Felicia tells the camera, boldly, that Ray is innocent—anyone who says otherwise is working for the government, or has been secretly poisoning her, or has been hired by her parents to ruin her life.

The most unsettling moment is when Felicia explains that she and Ray are “married”—common-law marriage, she says, because they’ve been living together and in love for so long. “I’m his honey-bunny lady,” she explains, “and he’s my honey-bunny man.” This comes moments after she shows off a well-organized drawer of countless pills and shelves of rations. At that point, it seems doubtful that a woman so deeply influenced by Ray’s paranoid worldview could ever make her way out of it, even with Ray out of the picture.

But Felicia continues to participate in interviews with Heinzerling in the months to come. Next time we see her, she and Isabella have parted ways and moved out of the house. Her legal counsel told her it would be the right move, Felicia says, as did her therapist. That latter detail feels like a quiet win, especially when we see how much healthier she already looks from being out of the house. Felicia’s hair is untangled, her face is fuller, and she’s seemingly inching closer to rational thought.

To see her removed from those subpoenaed videos where she’s at her most ravaged is a heartening, gracious triumph for the viewer and the show. The entirety of its third hour is devoted to Felicia’s slow, steady path toward forgiveness—of herself and, most touchingly, her family. At first, Felicia can’t fully dismiss Ray as her abuser, telling us that she believes much of what has been said about him is a lie. How could he have required one of her roommates to do sex work under her nose? How could he have lied about her parents cooperating with the police to destroy her?

In the film’s final act, however, Felicia has found both reality and grace. She was a victim, she has trauma, and she has a life to rebuild; through therapy, she has reconnected with herself. It’s beautiful to watch the physical and emotional change that she has undergone from when we first met her at the start of the series, especially through such an intimate lens.

Most vulnerable is when she allows the camera to come with her as she reunites with her parents for the first time in a decade; Felicia and her siblings had lost contact with both them and with each other as a result of their collective trauma. Such a reconciliation could come off as contrived in a docuseries without the empathy and hands-off approach that Stolen Youth employs so well. Instead, Felicia—a woman who, for years, had no control of her own life—makes the executive decision herself to call her mom and plan a meeting. After she hangs up the phone, she sobs with visceral, cathartic power.

The Rosarios reunite, and Stolen Youth ends with the siblings cooking and laughing together, their parents close by. Perish the thought that a true-crime show about such a disturbing, horrific crime that went on for far too long could end on such a hopeful note. The Sarah Lawrence College cult will probably always be best known for the sexual, psychological, and emotional damage it did to Felicia and her friends and family. But there’s a beauty to the fact that recovery is possible for these victims, even if such a truth is less sexy than all the illicit affairs. Hopefully future reporting can extend the same grace that Stolen Youth does to such complicated victims.