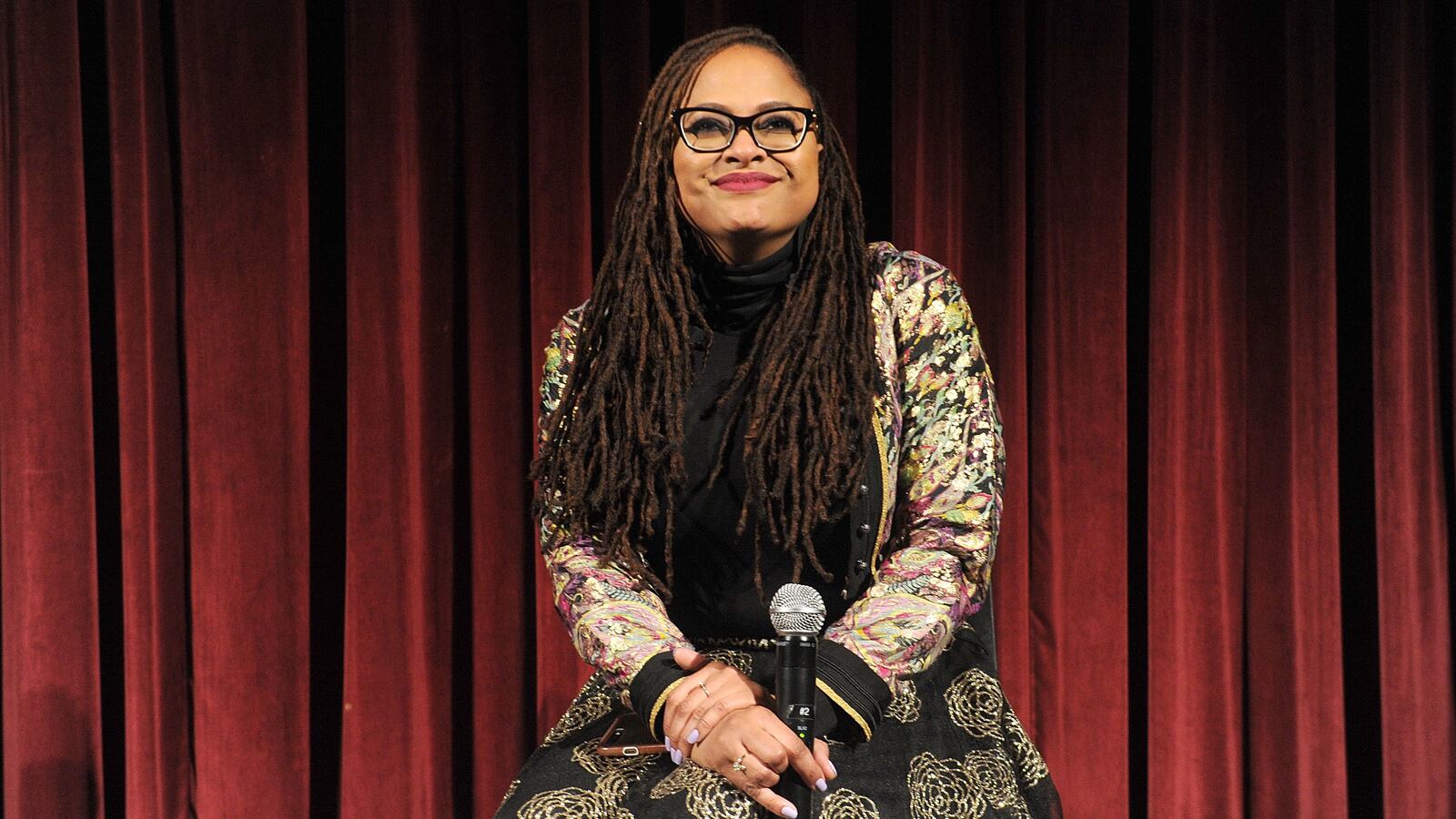

Filmmaker and producer Ava DuVernay—who helmed Selma, When They See Us, and the popular documentary 13th, about the connection between slavery and mass incarceration—is in the throes of a turbulent national election cycle.

DuVernay, who will be voting for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, has been tweeting incessantly about Trump’s many manipulations, yet, increasingly, her attentions have turned toward Black people. On Sept. 29, she tweeted, “For those who hadn’t been listening for the past 4 years, Trump just told you that he ain’t leaving and that he is a white supremacist. If that doesn’t get every American who is not white into overdrive to toss his ass - we may actually deserve what happens next.”

Later, when the president fell ill with COVID-19, DuVernay made a point of taking a holier-than-thou approach in addressing Trump, akin to the one sported by several Democratic politicians: “I truly hope you get well as you’re infected with a life-threatening virus and are physically ill. Also, you are a disgrace and a liar. You’ve cost hundreds of thousands their lives. And you’re a white supremacist. Get well. Sincerely. And after that, we’re going to vote you out.”

Shortly thereafter, DuVernay trained her attention on a Black woman, Vogue podcast producer Kinsey Clarke, for criticizing the director following her well-wishes for Trump. Clarke called DuVernay out for expressing shock at Trump’s continued cavalier attitude about the disease, which has put many aides, staffers, and frontline workers in danger, after DuVernay had quipped that she was ‘raised better’ than others who had rejoiced in the president’s own karmic reprisal. Through her criticisms, Clarke implied that the director cannot simply play both sides—the streets and the establishment. (The Daily Beast reached out to Clarke for comment and as of publication she has not responded.)

DuVernay has since deleted the original tweet in which she named Clarke and tagged Vogue, her employer, though the message beyond the snitching remains: “Couple things. To all who tried to ridicule me for stating I don’t wish death upon anyone: 1) Feel free to spend your time/energy/spirit wishing for someone’s death. I won’t. 2) Rage, criticism, justice work can be expressed without soiling one’s soul, karma, mind.”

DuVernay’s “we may actually deserve it” tweet was rattling, though I first took it as a passionate person, disconnected and insulated perhaps due to their own fame and wealth, misdirecting their frustrations at an amorphous Black public. Powerful Black people somehow did this to other Black people when Trump won (apparently Black voters had not turned out in big enough numbers for Hillary, as former first lady Michelle Obama lamented in the documentary Becoming), when South Carolina gave Biden a primary victory over Bernie Sanders, and even again when it became clear that Black people are disproportionately endangered by the spread of COVID-19. Yet, the recurrence of this kind of bitter language doesn’t make it reasonable, and plenty of Black people with much less power than DuVernay have been willing to point this out, with the expectation that a woman who just conversed with Angela Davis—a paragon of both Black radical activism and humility—would be receptive to the criticism. Alas.

Beyond the condemnatory speech against the “non[-]white” masses, DuVernay’s coming after Clarke stuck out to me like a familiar red flag.

Earlier this year, DuVernay had sided with Oprah when the latter decided to step down from her role as an executive producer on the Russell Simmons #MeToo documentary On the Record, which focused on three Black women’s alleged experiences of being sexually assaulted by the record producer. Oprah had misgivings about the way some of the stories were represented in the film, and initially gave very vague statements before confirming that she did believe all the women who came out against Simmons and had not at all been influenced by the accused music mogul to exit the project. Oprah told The New York Times that DuVernay helped her make that decision and even gave a harsh appraisal of On the Record’s two white directors, Kirby Dick and Amy Ziering, ability to “[capture] the nuances of hip-hop culture and the struggles of black women.” Many Black women who saw the film felt differently about On the Record’s depiction of hip-hop culture, and found it to be a meaningful exploration of misogynoir in the industry. (I generally liked the film, though in my review did criticize the directors’ decision to center the experiences of Drew Dixon, an upwardly mobile light-skinned Black woman, over and above anyone else’s.)

Perhaps, what had been important to Oprah, and by extension DuVernay, was whether such a sought-after name brand should be on something that didn’t fully represent either woman’s view of the world. After having seen the film, I felt that it would’ve made sense for Oprah to come to some kind of compromise with the directors at such a late stage, if only to make a powerful statement against a man who held considerable weight in the industry and yet had so thoroughly abused it (assuming that Oprah was telling the truth when she said she still believed the women). Wouldn’t an act of solidarity with women in hip-hop, channeled through a film that sought to tell their stories—and did a decent job of it—come before an editorial disagreement? Oprah had already supported Dan Reed’s Michael Jackson child-abuse documentary Leaving Neverland, having neither produced nor overseen it in any way. Why such a different standard for a film about Black women’s experiences with abuse in entertainment?

Powerful people, no matter their identity, can themselves become cultural gatekeepers rather than groundbreakers. DuVernay has made a career off of reinterpreting history on her own terms, to varying results, and her distribution company, Array, has been responsible for getting excellent films by new directors to a wider public—most recently Residue, a film tackling the effects of gentrification in a Washington, D.C., neighborhood, has made waves. Yet her very vocal public positioning seems to be much less in solidarity with Black people than it is in power amongst those in entertainment and beyond it. This would be the legacy of Oprah, Jay-Z, Puff Daddy, and even Kanye West, and not of William Greaves, Nina Simone, Ruby Dee, and Ossie Davis, or the L.A. Rebellion.