Dr. Mark Hyman — the great soul who convinced Bill Clinton to radically change his diet, and hence his health — is a believer in “functional medicine.” Rather than separately treating particular diseases, such as diabetes or heart disease or obesity, functional medicine treats the underlying biologic causes.

American politics urgently needs a Dr. Mark Hyman. It desperately needs an analogous “functional politics.” The pundit-sphere is filled with analysts diagnosing disease after disease, each offered with its own cure. The problem is the Senate. The problem is the House. The problem is the Republicans. The problem is the Tea Party. The problem is too much money in politics. The problem is too few participating in politics. The list is endless, and as it grows, endlessly depressing. What is a nation to do?

A functional politics, however, would ask how these problems are linked. Is there one that induces the others? Or one which if cured would make curing the rest much easier?

Consider Howard Fineman’s latest article as just one example. Fineman enumerates “15 Reasons Why American Politics Has Become An Apocalyptic Mess,” each summarized in just one paragraph. Here’s his list:

1. The Tea Party

2. Slow Growth

3. Obamacare

4. Scorecards

5. Two Cultures

6. Congressional Ignorance

7. Gargantuan Money

8. No Big Tents

9. My District Is My Castle

10. The End Of 'Regular Order'

11. They Either Don't Know Or Hate Each Other

12. Misjudging Obama

13. The New Iowa

14. Apocalypse America

15. You're Not My President

These “reasons” are linked—or at least, almost all of them are. But to see how, we must set the context a bit more clearly.

Since Newt Gingrich became Speaker, and the Republicans took control of the House in 1995 for the first time in 40 years, the culture of Congress as undergone a radical change. That change was induced by increased inter-party competition: At each election, the control of Congress is now effectively up for grabs. Each party thus fights ferociously to secure control, by fighting hard to win the next election.

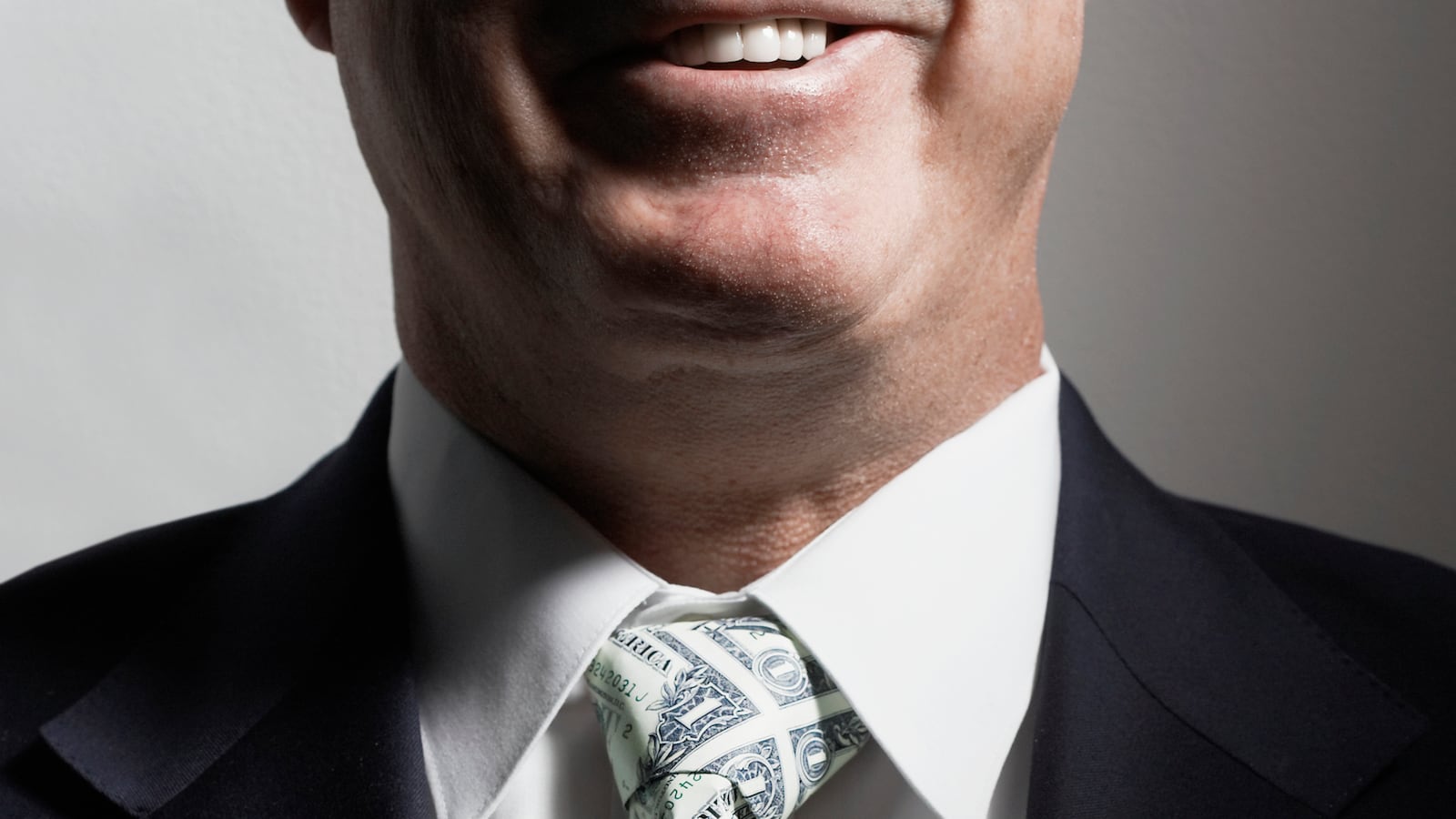

Elections cost money, so the day-to-day struggle of both parties is the fight to raise more and more money. Congress thus works less and fundraising by Congress increases.

In the old days (aka, before the Tea Party), much of that fundraising was linked to government spending. Earmarks, as Robert Kaiser describes in his fantastic book, So Damn Much Money, became the currency of the realm. And as government spending could be channeled through the earmarking process, it inspired campaign contributions by the earmark-obliged.

But after the election of 2010, the Tea Party put an end (basically, not completely, but certainly fundamentally) to earmarks. And so the strategy of fundraising has had to shift. No longer is funding linked to government spending. Increasingly it is tied to government stalemate. “Just sell ‘no’” became the mantra for the lobbying shops on K Street — with one even explicitly promising to create Senate holds and filibusters to prevent legislation from passing.

The strategy is different for the politically active base. Extremism with the base is the best fundraising strategy. Hatred and vilification are its fuel. Chris Murphy (D-CT), the Senate’s youngest Member, reports that emails to his list attacking Republicans raise three times the money that emails praising Democrats raise. The same is certainly true the other way around. As in every war, in the permanent war that is now D.C., we rally our side by demonizing the other. And of course, once we’ve succeeded in proving the other side is the devil, it becomes a bit difficult to strike a deal with that devil.

Against this background, Fineman’s list is a bit more digestible. The key is #7, Gargantuan Money, and the endless struggle to raise money. That struggle is aided by #3 (Obamacare) and #15 (You're Not My President), as well as #4 (Scorecards). Obamacare, the epithet, has little to do with Obamacare the insurance program; it is instead a lightening rod bolted to the President, which then inspires a certain kind of grassroots funding. So too with scorecards; politicians now work to score well on the report cards of lobbying and interest groups to ensure funding. And so too with #13 (The New Iowa) — a perpetual presidential campaign tied also to the endless need to raise money.

Gargantuan Money also ties to polarization: If extremism excites passion, then the extreme wings of the parties will be the most successful in fundraising. Hence the significance of #1 (The Tea Party), #8 (No Big Tents), #14 (Apocalypse America), and over time #5 (Two Cultures). Number 9 (My District is My Castle) is the product of gerrymandering, not polarization. But gerrymandering both lowers the cost of campaigns for a party overall, since there are fewer competitive races that a party must help fund, and increases the incentive to fund the extremes (if indeed the extremes can fund more easily).

Gargantuan Money also helps explain the increasing institutional dysfunction of Congress. Of course there is #6 (Congressional Ignorance). Who has time to read when there is fundraising to do? The same with #11 (They Either Don't Know Or Hate Each Other): one Member explains having lunch with other members just six times in six years, “if you have time for lunch, you have time to fundraise.” And, of course, there is #10 (The End of Regular Order). The very agenda of Congress is driven by what might flush the most money into campaign coffers. That has no relationship to order, regular or not.

Money doesn’t explain everything. It doesn’t explain #2 (Slow Growth), or at least immediately. Maybe it’s because Congress is so distracted by endless fundraising that it can’t address the issues that might actually help the economy. And money certainly doesn’t explain #12 (Misjudging Obama), at least so long as the President isn’t himself raising money. Indeed, the character of the President that we’re now seeing is precisely the character that has been covered up by his own six-year struggle to raise the money he needed — a battle that is tempered now that reelection is past.

So 12 of 15 explained by just one — not bad for a theory, and not even bad for the Republic. Because functional politics gives us a strategy, there is at least one clear thing to fix. If we changed the way we funded elections, we would change this other dozen too. Not necessarily fix perfectly; no one’s promising utopia. But at least we could get something good enough for government work.

Of course, it’s a party pooper who simplifies so radically. Single causes are boring, and simple causal accounts are always incomplete. Money might explain polarization, but it doesn’t explain all polarization. The same with each of the stories I’ve told above — money is just part of the account, if it’s a part at all.

But the critical point is this: Money is the part we could fix. Congress is so competitive because of who we’ve become as a nation — demographics, and the like, shifting slowly over many years. But we can’t ban Republicanism, and Texas is not going to secede. We are who we are, and the only important question is how we make it possible to govern us again, given who we’ve become.

Political scientists will remain skeptical. Their standards are high. In the academy, there is no truth without a statistical regression. So few will risk reputation or promotion by speculating beyond the facts that SPSS will whisper.

But in the middle of a crisis, certainty is an expensive luxury, and one we can’t afford anymore. We need to tackle the problems that explain most of our problems first, and soon.

For remember, there was only one clear victor in this latest governance collapse: the war chests of the radicals who brought this government to its knees. We lost $24 billion. They raised millions.