If we’re ever going to send people to Mars, we’re going to have to deal with one big problem: We just don’t know what will happen to the human body there. Human beings have never ventured beyond the moon, so when we finally set foot on another planet we’ll have to deal with eating strange food, living in a tiny box, and tromping across miles of dusty desert in a spacesuit. If these future explorers are going to have any chance of survival, we’ll need to know more about Mars might do to their bodies and their minds.

Space agencies like NASA aren’t big on leaping into the unknown, so they’re already trying to predict what effects a Mars mission might have on the human body. It’s not easy to guess that in advance—but one way they’re trying to learn about these consequences is through analog (or closely similar) missions.

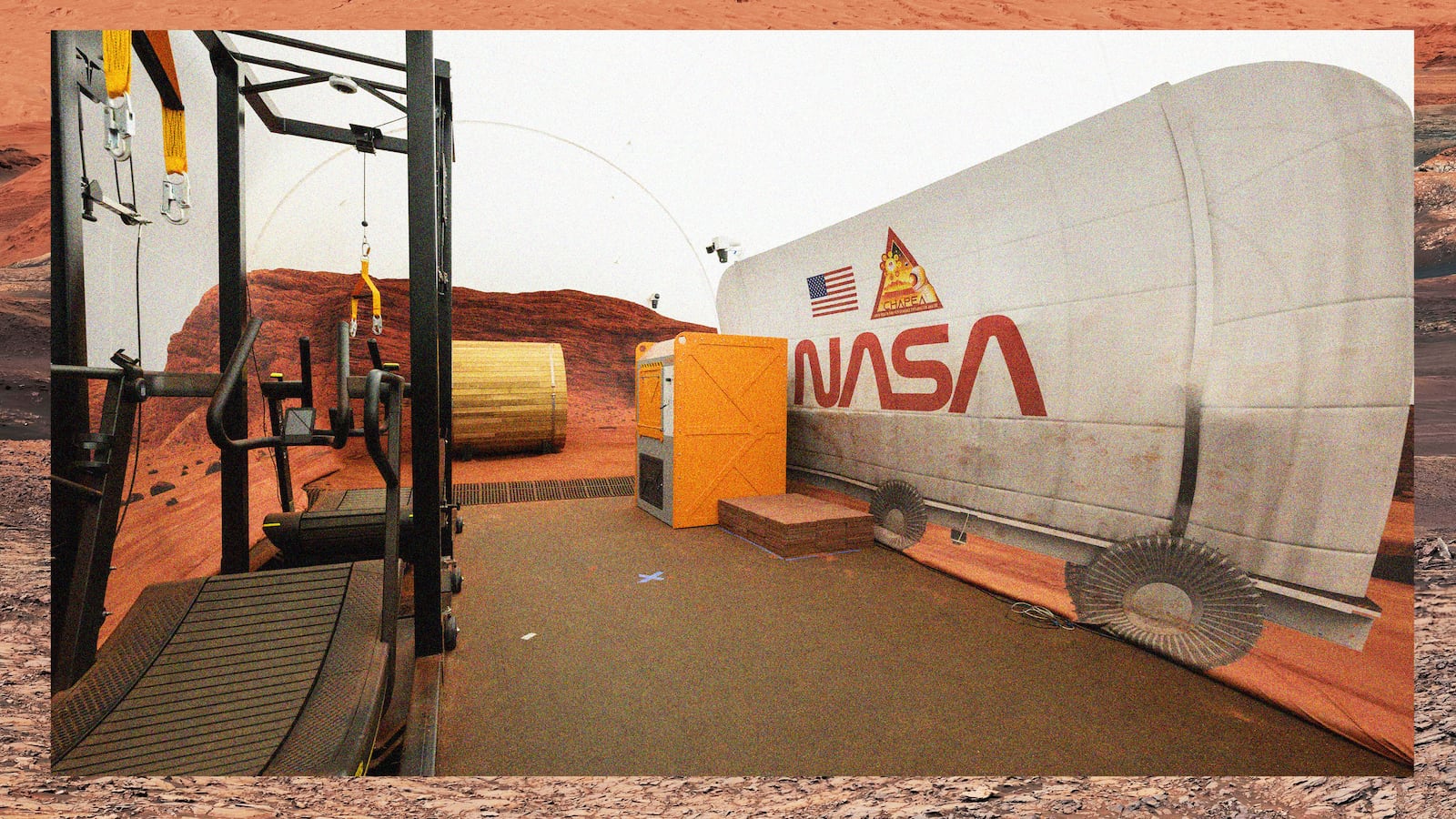

The Crew Health and Performance Exploration Analog (CHAPEA) mission will begin next month, with four crew members entering a 1,700 square foot enclosed bubble at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Specifically, they’ll live in a 3D-printed habitat with a 1,200 square foot Mars-like sandbox where they’ll perform simulated missions, all to see what it would be like for a real crew to live on the red planet.

NASA’s simulated Mars habitat includes a 1,200-square-foot sandbox with red sand to simulate the Martian landscape. The area will be used to conduct simulated spacewalks or “Mars walks” during the analog missions.

Bill Stafford NASA-JSC Houston TexasThe mission seeks to learn how being enclosed in this environment affects the crew’s health, both mental and physical, so that we can be ready for the kinds of challenges that astronauts would face on a real mission to Mars.

“This is the first NASA-run analog that’s going to be one year long,” and which will simulate life on another planet, Raina MacLeod, CHAPEA deputy project manager at Johnson, told The Daily Beast. Previous analog missions have been just a few weeks long and have looked at particular factors like psychological well-being, but this is the first time NASA will be looking at health over the long term.

The mission will investigate how factors like the diet available to astronauts might affect their immune systems, and how isolation might affect their health as well. By controlling the crew’s diets, environment, and activities, the research team can understand how all these different factors affect each other.

“That’s part of what really makes this a unique project and a unique study,” MacLeod said.

The CHAPEA crews will live and work in a 1,700 square foot, 3D-printed habitat located at NASA’s Johnson Space Center. The habitat includes four individual living quarters for the volunteer crew.

Bill Stafford NASA-JSC Houston TexasThe participants—who include a research scientist, a structural engineer, an emergency room doctor, and a nurse—will be locked away for a full year and will only be able to talk with the outside world via a delayed communication system. That’s to simulate the up to 22-minute delay each way that exists between Earth and Mars, meaning that future astronauts will have to be ready to make decisions without having mission control to advise them.

“We’re really focusing on the resource restrictions that we are expecting at Mars—like spaceflight food systems, isolation and confinement, or the time delayed communications,” MacLeod explained. Each of these factors can affect not only the crew’s mood, but also their ability to perform their jobs, and to deal with the challenges which would arise on a long-term space mission.

There are challenges on Mars which the analog can’t simulate like the lower levels of gravity, the danger of radiation, and psychological factors like the fear of death. There are health implications that will need medication and carefully planned exercise routines.

But overall, “the simulations are quite realistic,” according to Francesco Pagnini, a professor of clinical psychology at the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore in Italy who works on the psychology of space exploration but is not directly involved in the CHAPEA project.

Some of the biggest challenges for future space exploration will be not only keeping astronauts physically healthy on a months-long mission to Mars and back, but also keeping them mentally well. “On longer-duration missions, things will get quite challenging from a psychological perspective,” Pagnini told The Daily Beast.

While the excitement and wonder of space exploration is a big motivating factor for astronauts and scientists alike, the day to day grind of being trapped in a confined space for months can be draining—not to mention the complex and often drama-filled group dynamics any small crew will have to deal with.

A view through the airlock, which connects the CHAPEA habitat to the sandbox area, where crew members will conduct simulated spacewalks.

Bill Stafford NASA-JSC Houston TexasFor example, imagine a housemate who leaves their shoes lying around, Pagnini explained. What starts off as a minor annoyance can escalate to a serious source of conflict when you have to deal with it every day—especially when there’s no option for you to take any time away from each other. On top of that, your house is also on another planet and you’re millions of miles from your family and friends.

That’s something that the analog crew will learn about during their training. They will be entering the habitat in June, but will spend one month before training at the Johnson Space Center. There they’ll learn how to participate in the analog and tips on how to get along with each other. “They will be learning everything from how to be good roommates to how to use their IT systems,” MacLeod said.

It won’t be all roommate drama. The crew will also be trained on the simulated tasks they’ll be doing while in the habitat. These tasks are similar to the scientific research jobs that a Mars crew would be doing, like collecting samples, doing maintenance work, and exploring the Martian surface. This work can be physically demanding, and it might be difficult for a crew who have been living off packaged food for months.

To simulate leaving the base camp and traveling across the planet on a Mars walk, the analog crew will begin by getting into simulated spacesuits and opening the “airlock” of their habitat to enter the sandbox. There they’ll complete a host of tasks like locating geologically interesting rocks and documenting them.

Of course, a real Mars crew wouldn’t just be working in the immediate area around their habitat, so the analog crew will need to simulate walking long distances to get to areas of interest. For this, they’ll be utilizing an area next to the sandbox where crew members will put on VR headsets and walk on treadmills to replicate walking several kilometers to complete tasks in a digital environment.

The analog crew will also be testing out technology for remotely controlling rovers and drones, similar to the Perseverance rover or Ingenuity helicopter, which are currently on Mars. The crew will be able to control these bots from within their habitat, using them to look at the topography of an outside area—which is useful for planning out routes for exploration.

Throughout all of this, a team outside the habitat will be monitoring the crew’s health by analyzing blood samples and looking at data from wearable trackers, as well as getting the crew to answer surveys about their mood and team morale. They’ll see how the crew’s health develops over the year and whether they run into any problems physically or mentally.

“We’re hoping to learn a lot about how the crew’s health and performance changes,” MacLeod said. This information will help design the first actual missions to Mars, and help space agencies like NASA to anticipate the health challenges that might arise from putting people on the surface of another planet for a year or more.

Getting people to Mars is going to need some wild new technology, from rockets to habitats, but even more than that it’s going to require us to understand the human body in a new way. We’ve evolved for millions of years here on Earth, and leaving our planetary neighborhood behind is going to stretch astronauts physically and mentally—but now at least we’ll have some idea what to expect.