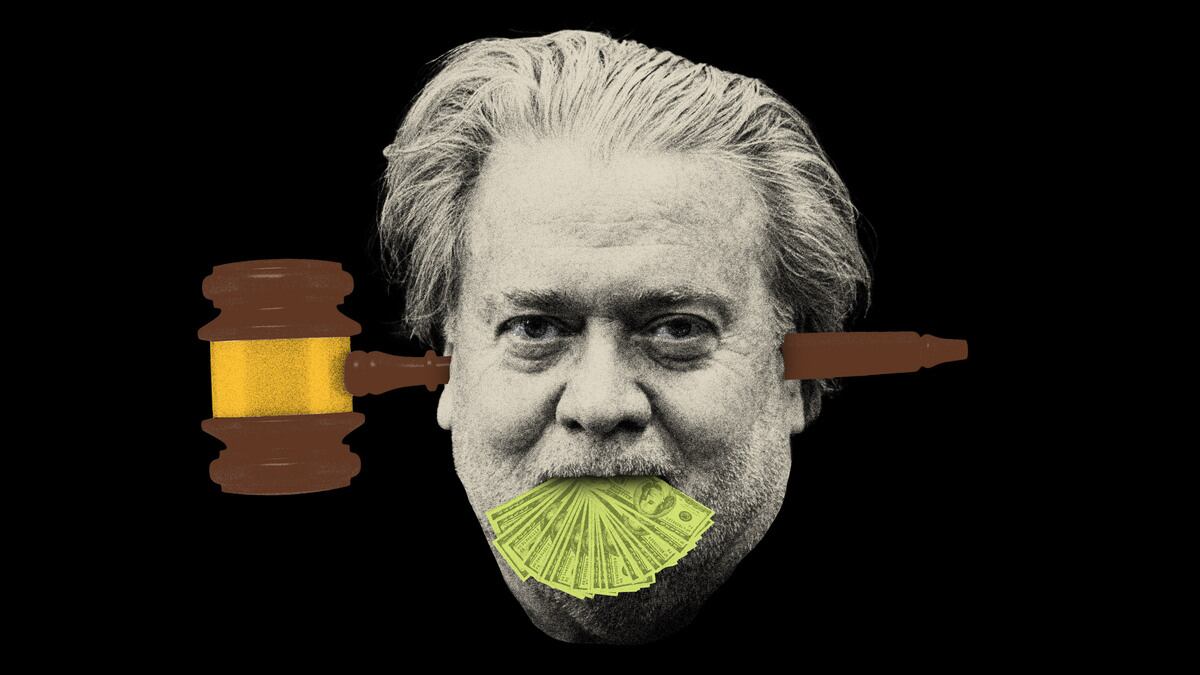

When President Donald Trump pardoned Steve Bannon in the closing hours of his presidency, it seemed like the right-wing media personality—and once chief strategist for Trump—had successfully evaded any repercussions for his involvement in a scheme that sent some of his partners to prison.

Double jeopardy laws, of course, prevent someone from being prosecuted twice for the same crime.

But there’s a curious reason why Bannon can’t raise the double jeopardy defense before his upcoming state court trial and make the case disappear: New Yorkers saw this coming.

“The law changed in New York, specifically because Trump started handing out pardons. New York State took the position that these people need to be answerable to crimes they committed in New York State,” explained Diane Peress, an adjunct lecturer at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

It all comes down to the way former federal prosecutor Todd Kaminsky, then a Long Island state senator, noticed how Trump was “corruptly using the pardon power” to shield himself by saving his powerful friends.

In 2019, then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed that bill into law, closing what the governor called an “egregious loophole.” Local New York prosecutors were now empowered—under certain circumstances—to pursue criminal charges against a U.S. president and his associates who’d received a presidential pardon. Politicians had slipped key exceptions to the double jeopardy rule.

For example, Trump couldn’t shield himself with a self-pardon if he were accused of “enterprise corruption,” one of several criminal charges that prosecutors have allegedly been considering over the way he appears to run the Trump Organization like a mob.

The new law also ensured that his associates could still be prosecuted if a pardon came too soon, such as in Bannon’s case.

Bannon, who has 356 days to prepare for a New York trial, is accused of quietly enriching himself with donor money from a nativist GoFundMe campaign to build Trump’s Mexico border wall. The case is essentially the exact same one as the federal proceedings two years earlier that, before trial, fell apart when Trump swooped in and saved him.

But in New York now, it’s only considered double jeopardy when a person has been fully prosecuted twice. That is, when someone was indicted and pleaded guilty—or, at the very least, had a jury sworn in.

The federal prosecutors at the Southern District of New York, however, never got Bannon’s case to trial. Trump used his powerful presidential authority to kill the investigation into his former White House chief strategist before federal prosecutors could get to that stage.

And that inconvenient timing means the Manhattan DA can go after the right-wing media personality for his role in “We Build the Wall,” the GoFundMe that ludicrously promised to keep Latin American migrants out of the United States by amassing private funds to construct a wall at the southern border—even though the feds had proof that the small cadre of men leading the project had siphoned off donor funds.

Prosecutors were still gearing up for a future trial when, on Jan. 19, 2021, a yellow-tinged letter bearing Trump’s name and a Department of Justice seal suddenly appeared in the federal court docket. It detailed how Bannon had received “a full and unconditional pardon” for that criminal case and “for any other offenses… that might arise” in connection to it.

The feds went on to secure convictions against Bannon’s three other business associates, who were punished for looting the purported charity. Brian Kolfage, a wounded and decorated Air Force veteran who served as the face of the project, was sentenced in April to more than four years in prison. Andrew Badolato, a project financier, got three years. Colorado businessman Timothy Shea, whose first go-around ended in a mistrial, was ultimately convicted and is set to be sentenced this month.

But Bannon got off.

Peress, who teaches at John Jay’s New York City campus, decried how the letter clearly violated the spirit of presidential pardon powers.

“This is some kind of blanket get out of jail free card. It doesn’t work that way,” she said.

Tess Cohen, a former Manhattan prosecutor who’s now running for Bronx DA, stressed that the way Trump got his buddy off the hook totally disregards the traditional meaning of a pardon.

“The vast majority of the time pardons have been used, someone has served a significant amount of time and there’s a feeling that the punishment is excessive… or when technically the law was violated but the specific set of facts is unjust, like when people illegally vote but it’s an accident,” Cohen said. “With Steve Bannon, you had a pretty typical fraud. There’s nothing special about it.”

When Manhattan DA Alvin Bragg Jr. unveiled a grand jury indictment against Bannon last September, his prosecutors revealed a series of damning texts that purport to show how he brazenly shifted money around thinking he’d never get caught.

So far, the Manhattan DA’s office has a 1-1 record for going after Trump associates who were saved by a pardon.

The first attempt failed. Bragg’s predecessor, Cyrus Vance Jr., tried to takedown the Republican political consultant Paul Manafort, who played a central role in the Special Counsel Robert Mueller investigation into Trump-Russia ties. The notoriously corrupt Trump campaign adviser got a presidential pardon just two years into his seven-year sentence for financial corruption and obstruction of justice. Vance, then the Manhattan DA, pursued mortgage fraud charges against Manafort that were later tossed out by a state appeals court. (The court determined that Manafort actually was protected by the double jeopardy rule.)

But the Manhattan DA’s second try succeeded. Much like he did with the Bannon case, then-President Trump, in his final hours in office, killed off a case by federal prosecutors in Brooklyn who had targeted a family friend: Ken Kurson, once the editor of a New York City newspaper that was owned by Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner. But Vance went after Kurson anyway, overcoming the double jeopardy arguments and getting him to plead guilty to cyberstalking.

The question now is whether Bragg can pull off the same feat against Bannon—while he simultaneously juggles the most historic case his office has ever undertaken: a criminal case against Trump himself.