As we approach this year’s near simultaneous celebration of Easter and Passover, why don’t religion writers and influential clerics begin to fret over perplexed families that must do battle with the awkward, unavoidable “April Dilemma”?

Every winter, articles abound over the December Dilemma, highlighting husbands and wives in mixed marriages struggling to honor Christmas and Chanukah jointly, or focusing on divided clans with their share of nonbelievers unable to decide whether to center festivities on Jesus or Santa.

The spring festivals speak to us with greater clarity and force because they’re unequivocally and inescapably religious.

Christmas has been largely secularized around the world, but efforts to drain faith-based messages from the Easter holiday have for the most part failed miserably. For one thing, it’s much tougher to secularize a festival about resurrection, which doesn’t happen all that often, than one about birth, which in one form or another happens all the time.

So if Easter isn’t religious, it’s empty and inconsequential. Few Americans feel deep emotion or profound sentimental attachment to the procedure of rolling colored eggs. The Easter Bunny remains an indistinct personality who’s gained limited traction, but Santa Claus has become a distinctly beloved figure around the world. Consider the difference between cherished Kris Kringle movies (Miracle on 34th Street or The Santa Clause) and the rancid recent release Hop, just out on DVD, with Russell Brand voicing the Easter Bunny’s son, who leaves the family business and goes out to Hollywood to ogle starlets. Families enjoy watching Santa films to savor the season, but children should only view Hop as a form of punishment if they’ve been very, very naughty.

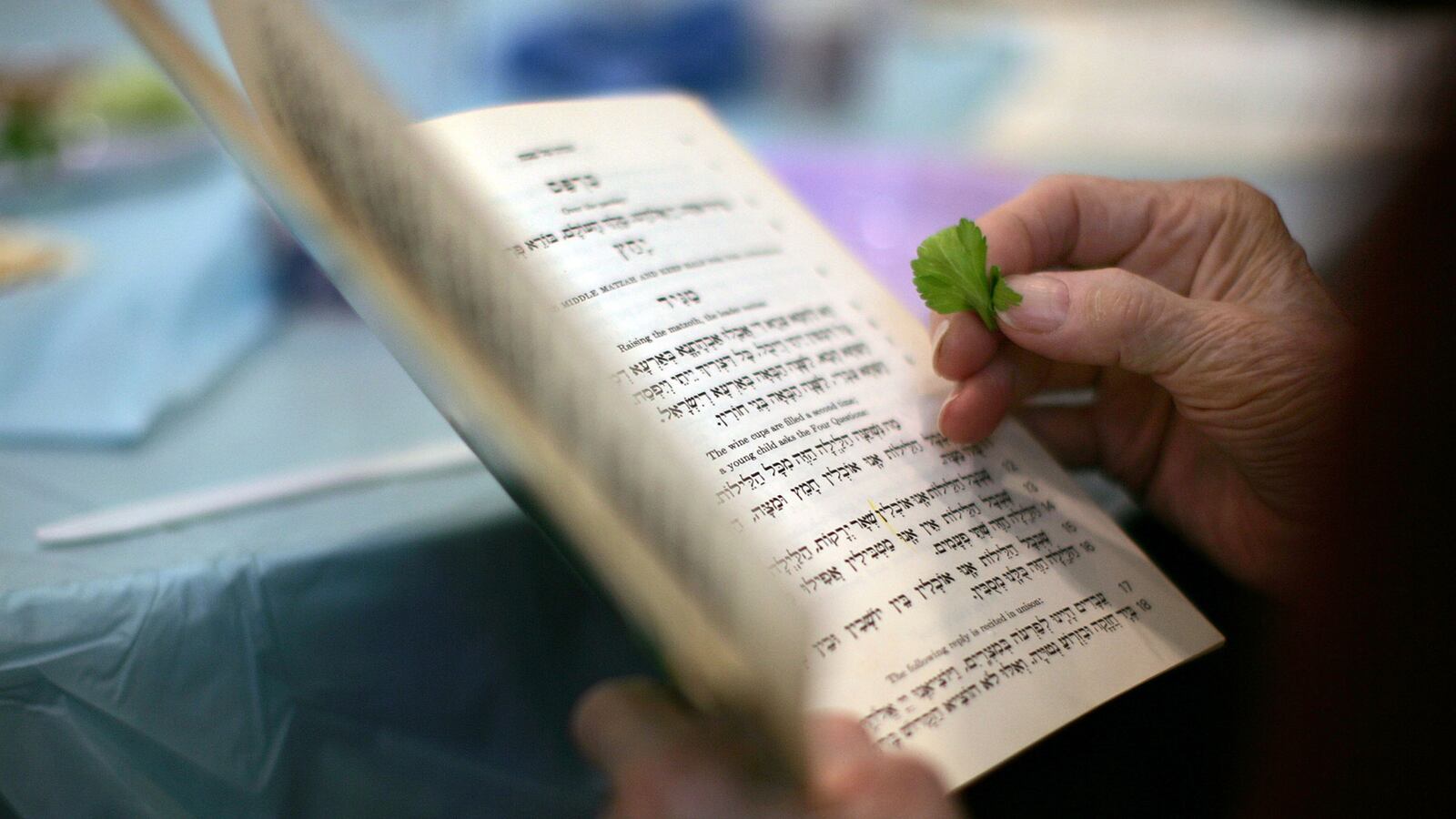

Attempts to separate Passover from its religious roots have fared no better than the bid to secularize Easter, though Chanukah has been much easier to dismiss and diminish. Chanukah, after all, counts only as a minor festival in the Jewish calendar with no practical requirements other than lighting candles; its authentic religious message—purification, rededication—has been widely ignored. Passover, on the other hand, is a big deal, and the most widely observed of all Jewish occasions. Biblically mandated, it has elaborate rituals for an extended seder meal and a radical change of diet, even dishware, that’s supposed to last eight days.

Meanwhile, only masochists savor the matzo—traditionally described as “the bread of affliction”—for its own sake, but the latkes of Chanukah seem tasty even without religious associations. Those who prefer not to think about God can be perfectly comfortable with Chanukah as commemoration of a liberation struggle, honoring the military genius of Judah the Maccabee. But during the Passover season, atheists and skeptics are stuck: it wasn’t civil disobedience or inspiring speeches by Moses—he was tongue-tied, remember?—that got the Hebrew slaves out of Egypt. That deliverance required a series of miracles by a supernatural God.

The spring festivals both count as tougher, more demanding, more personal, and surprisingly less controversial than the winter celebrations. Easter insists that Jesus died and rose again for you, personally, not for some other guy, or just for a group of disciples long ago. The Passover liturgy recited at the seder meal similarly demands that you experience the Exodus as if you escaped from Egypt yourself, not your great-grandfather or your Orthodox Uncle Max, and you owe the Almighty undying gratitude as your personal liberator.

The religious messages in the April holidays are pointed, unequivocal, impossible to fudge. There’s no annual “War on Easter” to compare to our annual and increasingly tedious “War on Christmas” because no one tries to claim that Easter is a secular occasion or attempts to empty holy week of its New Testament substance. While ardent believers seek to “Put Christ back into Christmas,” there’s never been a comparable effort to “Put Christ back into Easter”—taking him out of the holiday is unthinkable. Sure, Christians can bring their skeptical, non-believing friends along with them to experience an inspiring sunrise service this Sunday morning, but the worshippers will be honoring more than the new buds of spring.

In America’s wonderfully pluralistic and open society, the clear, fervent expression of religious messages makes for less conflict, not more. In this country, Christians have never repeated the horrors of medieval Europe, when the Easter holiday frequently offered an excuse for violent persecution of Jews as “Christ-killers,” producing bloody pogroms that interrupted traditional Passover celebrations. Here, increasing numbers of Christians seek to experience Passover, not to suppress it, hoping to familiarize themselves with some of the rituals Jesus may have performed at the Last Supper. This year, Jews around the world will revisit those traditions on the evening after Good Friday, when Passover begins at sundown.

No wonder that Jews and Christians can simultaneously enjoy the twinned seasonal expression of our distinct traditions, with little of the confusion or torment associated with the December Dilemma. In this sacred season, we see that religion isn’t a zero-sum game. A more devout and meaningful Easter for Christians in no way detracts from a joyous Passover for the Jews, just as a strictly observant Passover takes nothing away from the drama and impact of holy week.

A national religious revival need not favor one faith over another. The United States at large can benefit from more serious consideration of timeless questions. And even committed skeptics who opt out of celebrating the April holidays can welcome the universal messages of rebirth and liberation that all of America seems to need at the moment.