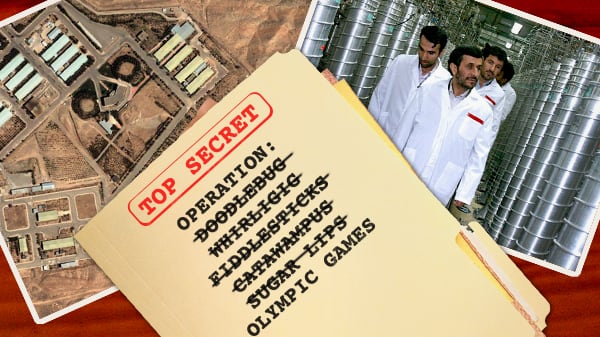

The code name that the Pentagon chose for its Stuxnet cyberoperation to hinder the Iranian uranium enrichment program—Olympic Games—has raised eyebrows in intelligence circles. To give the massive, international, and imminent operation a name that implies something that is massive, international, and imminent is precisely the opposite of what code names are intended to do. So what makes a good code name?

While the British Ministry of Defence uses a computer program to pick out words completely at random, the Pentagon has tended to choose code names that imply something invigorating and, if possible, morally uplifting, as much propaganda as secret cipher. The 1983 liberation of Grenada was code-named Urgent Fury; the 1989 attack on Panama was Just Cause; the 1991 attack on Iraq was Desert Storm; the Afghan War started off with Operation Enduring Freedom (after Infinite Justice was turned down as likely to inflame Muslims). The Iraq War began with Operation Iraqi Freedom (chosen after Operation Iraqi Liberation was recognized to have a somewhat unfortunate acronym). America has also launched Operations Restore Hope, Uphold Democracy, Shining Hope, Productive Effort, Provide Promise, and so on.

It was the German Army of the First World War that first came to use code names in their present sense, especially once it became clear that the Allies were tuning into their radio frequencies, but it was the Wehrmacht of the Second World War that came up with the most powerful and memorable of all military code names, including Barbarossa for the 1941 invasion of Russia (which was originally named Fritz, after a staff officer working on the project, before Hitler named it after a conquering German emperor), and Operation Winter Tempest (the attempt to relieve Stalingrad in 1942).

By contrast, the Allies started the Second World War with completely absurd code names, each more unmilitary and even wistful than the last. It was after he saw that the forthcoming U.S. bombing attack on the Romanian oilfields in August 1943 was going to be code-named Operation Soapsuds that Winston Churchill finally lost his patience and ordered that code names “ought not to be names of frivolous characters” or be “ordinary words” and furthermore that “names of living people should be avoided.”

Soapsuds was renamed the much tougher sounding Tidalwave. Churchill then ordained that code names should be taken from “heroes of antiquity, figures from Greek and Roman mythology, the constellations and stars, famous racehorses and the names of British and American heroes.”

Racehorse names perhaps spoke to Churchill’s own aristocratic upbringing, but it still seems surprising just how light-hearted, and sometimes flippant, code names had been before then. For up until August 1943, men went into harm’s way in operations with code names such as Bingo, Boozer, Bunghole, Cabaret, Cellophane, Chastity, Chattanooga Choo-Choo, Corkscrew, Duck, Grapefruit, Haddock, Hats, Horlicks, Infatuate, Jockey, Juggler, Lilo, Loincloth, Mallard, Manhole, Market Garden, Modified Dracula, Mutton, Nest Egg, Pancake, Pantaloon, Peanut, Puddle, Pumpkin, Raincoat, Razzle, Rhubarb, Rhumba, Sardine, Saucy, Seaslug, Skinflint, Spinach, Squid, Teacup, Wowser, and Zipper.

Perhaps it helped psychologically to minimize the lethal nature of these actions by giving them such frivolous titles, but no parent wants to know that a son lost his life in Operation Slapstick, Toenails, or Maggot, in comparison to the far more serious-sounding Retribution, Mailfist, Supercharge, or Musketeer.

Churchill also feared that the names of some operations might create “an air of despondency,” and it’s easy to see what he meant by the names for Operations Orphan, Batty, Moonshine, Penitent, Blot, Grubworm, Hasty, Deficient, Frantic, Lost, Rockbottom, Ratweek, Stalemate, and especially Taxable. For all that Olympic Games might sound a surprising choice for the entirely laudable operation presently being undertaken against the Iranian nuclear project, at least no one called it Toenails.