Prostitution is not necessarily something you want to bring up at your local feminist meeting, unless you’re trying to start a war. Perhaps the only common ground on the issue is the view that women should not be made into criminals for a crime in which they are the only victims. Whether you believe that no woman would freely choose prostitution over the kind of dehumanization that low-wage work can bring, or if you believe that prostitution is simply a trade like any other, victims of trafficking are victims who do not deserve to be made into criminals.

The way we treat sex workers now, both culturally and under the law, is that they are consistently degraded, branded criminals, and if they become the victims of violence (a real risk in any black market) they are nearly guaranteed to find themselves neither protected or served. I have never been a prostitute, but I have definitely worked in places where men paid women who were nowhere near fully clothed, and it was well known that if something went awry with a customer—in a perfectly legal establishment where no sex at all was happening because of cameras and bouncers—the police wouldn’t even bother to take a report. Women who work at strip clubs are assumed to be prostitutes, or the next worst thing to them, which meant that our safety was never a top concern among law enforcement or our employers. We were as likely to be investigated as helped if we were ever victims of a crime. It doesn’t take much of an imagination to extrapolate that it’s much worse to be in that same line of work but to a degree that made your living actually criminal.

The impact of criminalization on the public goes well beyond the damage to the people who find themselves working in the sex trade, whether they are trafficked or there of their own free will. The arrest, detention, and charging of women for what amounts to a moral sin—if a sin indeed it is—is costing the country millions of dollars that we simply can’t afford. This is why New York is thinking about moving replacing criminal charges for prostitutes with civil citations. There’s already a law which allows people who were victims of trafficking to vacate their convictions for prostitution and related charges. (A recent study released by the Urban Institute found that about 20 percent of the sex workers they surveyed had been trafficked at least once.)

New York, which has a decreasing crime rate and an increasingly loud chorus of citizens who support closing Rikers Island, is now weighing its options on how to treat sex workers, knowing that criminal charges are generally not the best way to intervene in a someone’s life if they need rescuing from a terrible situation. What it comes down to is this: Rikers Island is an internationally infamous hellhole, known for its inhumane treatment of inmates, its corruption, and its brutality—and it costs a lot of money. So the city is considering a plan to shut it down and build smaller prisons instead. To do that, they have to cut their inmate population. This is where decriminalizing low-level offenses comes in. The range of charges they’re considering dropping is wide: prostitution, fare jumping, publicly visible possession of marijuana, and possession of gravity knives among them.

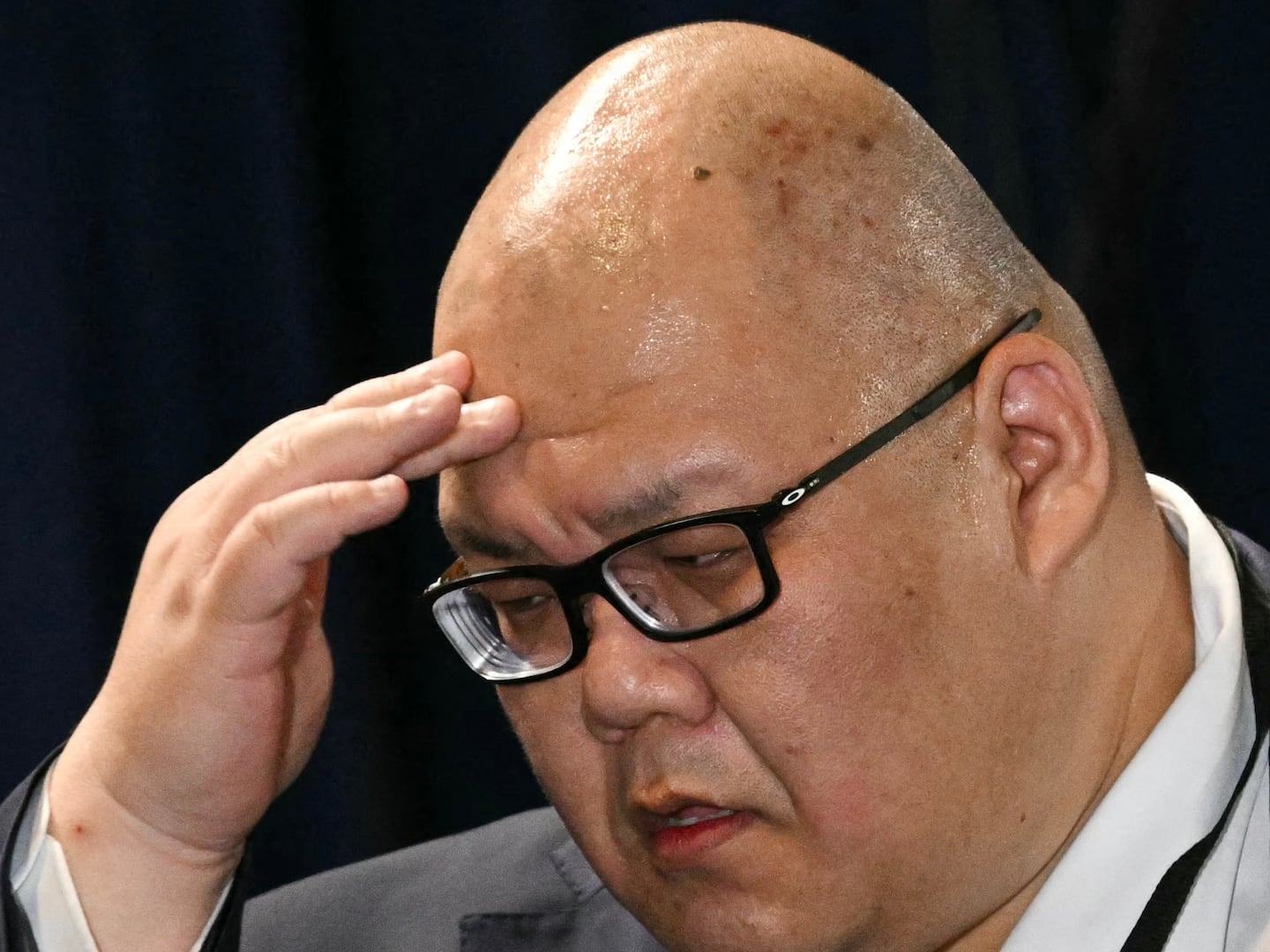

Mayor Bill de Blasio, who has railed against the horrors of mass incarcerations in front of church bodies, opposes these reforms, partially on the grounds of so-called public safety.

“While we appreciate the intent of the commission, these actions would generally have little impact on the jail population and, in some cases, could actually jeopardize public safety and are therefore not supported by the administration,” a mayoral spokesperson said. It’s hard to believe that fare jumping is a public-safety issue more than it is a public revenue issue. Low-level marijuana possession is becoming increasingly flat-out legal around the nation and we don’t seem to have gone full Reefer Madness yet. Knives might well be a public safety issue, but that’s no reason to pretend it’s on the scale with turnstile-hopping. And in no instance should a human trafficking victim be treated as a criminal.

If we’re meant to look at prostitution from a public safety perspective, it would make sense to create an environment with health services and access to justice, to combat trafficking and abuse. It would become much harder to traffic in women if those women could speak to the police without fear of arrest. If we are looking at prostitution itself and judging it a moral ill that should be criminally punished, then crack down on the customers.

Cutting the demand is one way to change a market; another is to provide it with a labor shortage. I would have preferred the choice between two good options instead of two demeaning ones, though it was what I had to work with at the time and I feel no particular ill effect from it years later. The sex workers I have known over the years have hated it or not minded it or enjoyed it to various degrees and it has always seemed to depend mostly on how much respect has been involved in their work. I have known victims of trafficking, the abusive-spouse kind that is more common than the cartels everyone pictures. But the one thing that’s true of all of them is they would have been much safer and in much cases much healthier if they had been able to relax sometimes instead of constantly carrying around the fear of arrest. And most of them would rather have been doing something else, if it would have kept the electric on.

If you want to get women out of prostitution, get them out of poverty.