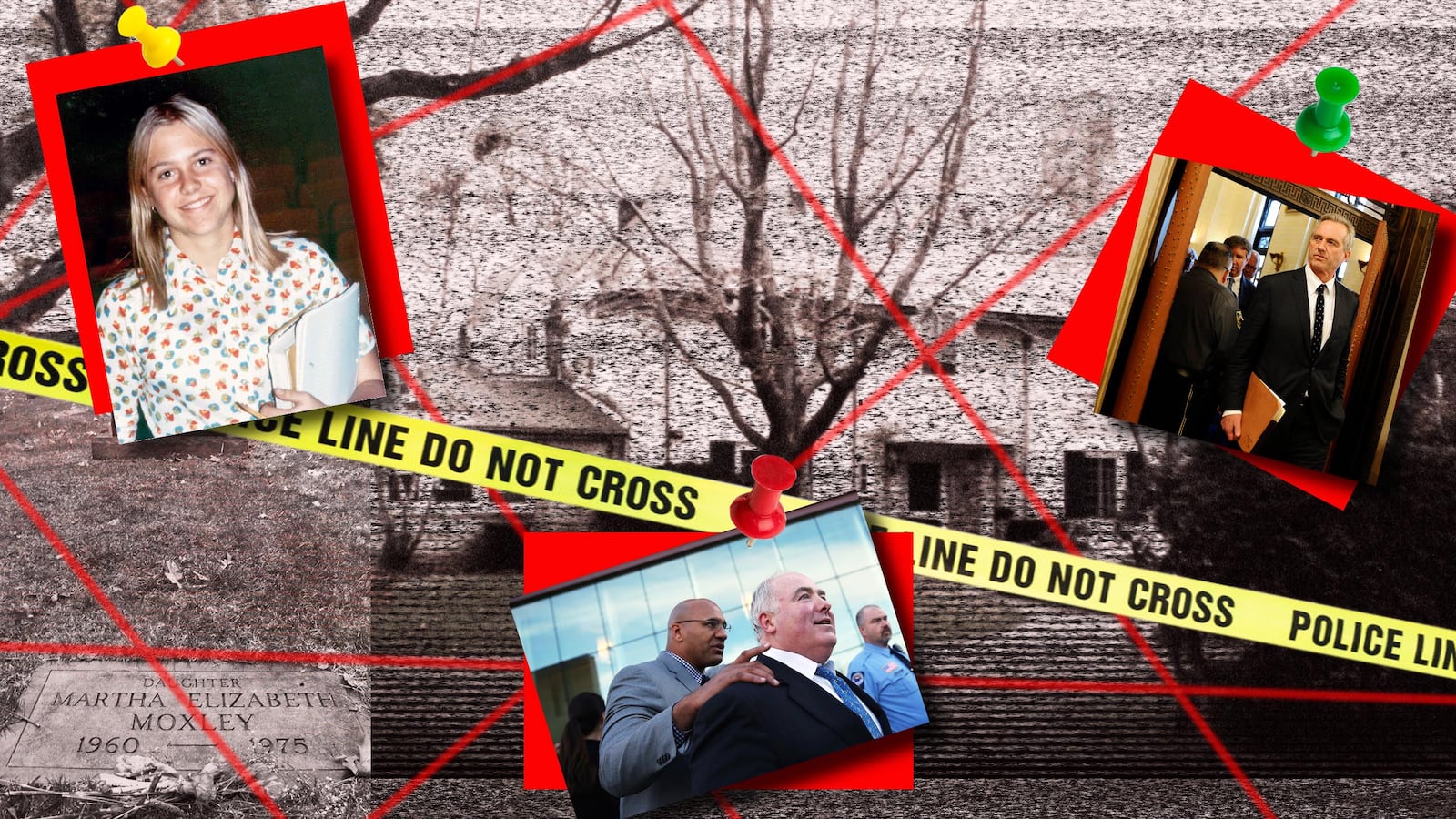

Welcome to the third installment on the murder of Martha Moxley, a Beast Files series for Beast Inside members only.

The new prosecutor in Martha Moxley’s murder, Jonathan Benedict, announced the indictment against Michael Skakel—nephew of Robert F. Kennedy—at a January 2000 press conference. Michael surrendered later that day at Greenwich Police headquarters.

His older brother Tommy Skakel—who had been the last person seen with Martha—subsequently spoke to a Greenwich Time reporter. “I obviously feel relief I’m not public enemy No. 1,” Tommy was quoted saying, adding, “I know certainly Michael didn’t do it.”

Tommy said of the murder and the accompanying suspicion, “I’ve lived with it more than half my life. It’s been devastating over the years.”

He told the reporter that his daughter, Elizabeth, who was then 10, had seen a TV program about the murder.

“She said, ‘Daddy I love you. I know you didn’t do this,’” Tommy recounted.

Michael’s lawyer was Mickey Sherman, raised in Greenwich, known more for being a TV talking head and commenting from the sidelines than for actually trying cases. Sherman was reportedly hired at the suggestion of fellow attorney Emmanuel Margolis, the longtime criminal defense attorney for the Skakel family and for Tommy in particular. Margolis did not have to say that the Skakels would be happy if Sherman were able to secure an acquittal for Michael without pointing a finger at the longtime leading suspect Tommy.

The family no doubt hoped the trial would also clear the Skakel name and part of the reason Sherman was hired may have been that he billed himself as being “media savvy.” The family may have been thinking that Sherman could serve as a counterweight to authors Dominick Dunne and Mark Fuhrman—who had both fingered Michael as the murderer—in the court of public opinion.

At the preliminary hearing and then Michael Skakel’s trial itself, that other family name—the one that can inspire the best in us but also lead us to suspect the worst, that has such psychic impact that it can slow a murder investigation without even being uttered—became an overt factor with the testimony of Gregory Coleman.

He was, by his own subsequent admission, high on heroin as he testified at the preliminary hearing that during his time at the Elan School—the residential substance abuse facility—he had heard Michael confess on more than one occasion to murdering Martha Moxley. Coleman had died of an overdose before the trial, but a recording of his testimony was played for the jury.

“The first words he ever said to me was, ‘I’m going to get away with murder. I’m a Kennedy,’” Coleman said.

That purported statement seems way too pat to have been believable, but it played into the flip side of Kennedy worship, the widely held notion that members of the clan act as if the rules do not apply to them. Many people had seen proof in William Kennedy Smith’s acquittal in the Florida rape trial that the rules too often really do not apply.

In this Connecticut murder case, the judge who ruled that it should be heard in adult court—even though Michael was a juvenile at the time of the crime—would no doubt deny that he was influenced by the defendant’s connection to the Kennedys. The jurors who heard the evidence in the subsequent trial would no doubt say the same. One juror would later say that they considered Coleman’s testimony to contain only “a grain of truth.” But the Kennedy name has too much psychological power not have had some sway.

Martha Moxley, who was savagely beaten with a golf club on Oct. 30, 1975, in Greenwich, Connecticut, at the age of 15.

Handout via ReutersThe defense lawyer Sherman may have inadvertently added to the Kennedy effect by seeming so confident from the very start, when he blithely allowed a cop and a lawyer onto the jury. The actual source of his cockiness likely was the weakness of the case against his client. There were no witnesses or physical evidence directly tying Michael to the crime. The former Elan residents who supposedly heard Michael confess had various credibility problems. Other Elan residents testified that Michael had been subjected to beatings and mass verbal assaults while being forced to wear the sign, “Ask Me Why I Killed My Neighbor,” from the time he rose in the morningto when he went to bed. He had been battered in a boxing ring until he switched from denying his guilt to saying he did not remember what happened that night.

The prosecution sought to provide a motive by calling a former Elan resident to the stand. She testified that Michael had told her he was blackout drunk on the night of the murder and felt that Tommy “stole his girlfriend.” But Sherman established during cross-examination that the witness had failed to mention Michael’s supposed jealousy when she appeared before the grand jury. Sherman got her to admit that she had only recalled Michael’s talk of Martha being stolen from him after reading Fuhrman’s book Murder in Greenwich, which theorized that jealousy as well as alcohol may have been factors.

As for the incident when Michael leapt from the car on what would become the RFK Bridge, shouting he’d done something bad and had to leave the country, Julia Skakel testified that just before the incident their father had caught Michael sleeping with one of their dead mother’s dresses.

Julia did acknowledge that shortly after the Lincoln departed for the Terrien’s house on the night of the murder she had seen a figure carrying something flash past in the darkness outside as she exited the house to take her friend, Andrea Shakespeare, home. Julie had previously reported calling out, “Michael, come back here!” But she now said the figure was much bigger than Michael and could not have been him.

And anyway, Michael had an alibi.

The autopsy results set the time of death no more precisely than sometime between 9:30 p.m. and 5:30 a.m. the next day. But both the defense and the prosecution were taking the position that the murder most likely occurred at approximately 10 p.m., shortly after the last report of Martha being seen alive and around the time dogs in the neighborhood began furiously barking while facing in the direction of her front yard. Sherman had several people ready to say that Michael was 20 minutes away at his cousins’ house and did not return until after 11 p.m.

But the alibi was called into question by the testimony of Julia Skakel’s friend, Angela Shakespeare. The friend had previously said she only had “a sense” that Michael had remained behind while the others drove off to the Terrien house. She now seemed more convinced.

“And from 1975 to today have you remained certain Michael Skakel was home when that car left?” the prosecutor asked.

“Yes,” she said.

The defense alibi witnesses who said Michael had in fact ridden off with the others all had a familial connection to him. Sherman had failed to track down and call to the stand one independent witness who was referred to in the police reports and who clearly remembered seeing Michael at the cousin’s house. That witness would have cast decidedly reasonable doubt on Shakespeare’s recollection that Michael had remained at the Skakel home.

Sherman may have placed unrealistic expectations on his main strategy, which was to present the family tutor Ken Littleton as an alternative suspect, a view that was long held by the man who had until recently been the state’s lead investigator, Jack Solomon. Sherman played a decade-old videotape of Littleton being examined by a psychologist. Littleton reported that his ex-wife, Mary Baker, had told him he had confessed during an alcoholic blackout in 1984 to having committed the murder.

“That’s when I said I did it,” Littleton could be heard saying on the video.

Sherman now asked Littleton on the stand if he had been speaking of the Murder of Martha Moxley.

“Correct,” Littleton said.

“Did you ever tell Mary that you stabbed Martha Moxley through the neck?”

“Yes,” Littleton replied.

Sherman seemed to have achieved a Perry Mason moment. The prosecutor, Benedict, then got a turn.

“How do you know what was said in the course of that blackout?” Benedict asked.

“From what Mary told me,” Littleton said.

“Did you kill Martha Moxley?” Benedict asked.

“No, I did not,” Littleton said.

Mary Baker was called to the stand. She testified that the investigator, Solomon, had hoped to elicit an actual admission by coaching her to tell her husband that he had confessed.

“Did he ever make an admission as to his complicity in this murder?” the prosecutor asked.

“Never,” she replied.

At one point, Sherman suggested that Littleton had been pathologically obsessed with the Kennedys. Littleton admitted that he had become paranoid during the summer after the murder and imagined that an ex-girlfriend had been doing the bidding of the Skakels and Kennedys when she injected him with cocaine “to blow my heart out.” He also acknowledged having later announced that he was “Kenny Kennedy,” black sheep of the clan. Sherman asked him why.

“Because JFK is my hero,” Littleton replied.

That did nothing to explain why Littleton might have killed Martha on his very first night at the Skakel house. He seemed at this moment less a viable suspect than a victim of suspicion in a case intensified by the often unstated but ever-present family name that his hero had made royal. He was certainly no Kennedy, but his life had been upended by a case that was originally botched and then revived in part because of just a tangential association with the clan. The situation must have already felt so surreal that it could not have been that far a leap for his delusions to have taken the direction they did.

Ken Littleton, a tutor for the Skakel family, who arrived on the night Martha Moxley was murdered.

Handout“My life was a mess. I was a bright, promising young teacher who graduated from one of the best schools in the country—all that was falling apart,” he told the jury of the time after the murder.

He nonetheless seemed convincing when he was asked once again about Tommy’s demeanor that night, shortly after the killing most likely took place.

“He was perfectly groomed, he wasn’t in an agitated state, he was perfectly normal,” Littleton said. “A gentleman.”

But Littleton had told police much the same thing during questioning after the murder. And Sherman was able to establish at trial that the Greenwich police had nonetheless sought to secure an arrest warrant for Tommy.

Oddly, or perhaps not so oddly if you consider that he was in essence working for the Skakel family. Sherman did little else to present Tommy as an alternative suspect. Sherman would later say that he did not like to present a “smorgasbord” of possible suspects, but he could not have been anxious to cause undue distress to the family that hired him, especially not when he seemed to view an acquittal as an all but sure thing.

Sherman had added reason to be optimistic when Belle Haven neighbor Mildred Ix recanted what she had told the grand jury in 1998. Ix—whose daughter, Helen, had gone with Martha to the Skakels on the night of the murder—had originally testified that Rushton Skakel Sr. had confided to her that Michael was concerned he might have murdered Martha during an alcoholic blackout.

“He said Michael had come up to him and he said, you know, ‘I had a lot to drink that night. I would like to see—I would like to see if—if I could have had so much to drink that I would have forgotten something and I could have murdered Martha, and I would like to make sure at [sic] that night knowing something like that happened.’ So he asked to go under sodium pentothal or whatever it was,” Ix had testified before the grand jury.

Ix now took the stand and initially said that the encounter had never taken place. She then allowed under the prosecutor’s questioning that the elder Skakel had said something about sodium pentothal, but had never suggested that Michael feared he might be the killer.

“I know Rush never, ever heard from Michael that he ever killed anyone,” Ix now testified. “I assumed something that was really in my heart of hearts. I put in Rushton Skakel’s mouth what I actually thought. I’m sorry.”

The 78-year-old Skakel patriarch was called to the stand despite the efforts of his lawyers to have him excused because of what doctors diagnosed in writing as depression and dementia. The judge held a brief competency hearing with the jury out of the room in which Rushton Sr. was asked to name his children.

“I wish you wouldn’t ask me that,” he said, before naming six of the seven with some apparent difficulty.

The judge nonetheless ruled Rushton. Sr. competent and the jury was brought in. The prosecutor asked about the day of the murder. Rushton Sr. testified that he had been away on a hunting trip when he learned of Martha’s death, but that was not what had prompted his return the next day.

“I didn’t return early,” he said. “It was a hunting trip and the hunting was over.”

He could remember speaking to his children upon arriving home, but he could not remember anything that was said. He also could not remember asking Littleton to take the older kids away for the weekend or exactly why Michael was subsequently sent to Elan. He also professed to have no recollection of the supposed conversation with Ix even after the prosecutor read aloud from her grand jury testimony.

When it came time for cross-examination, Sherman had only one question.

“What happened in this country on Sept. 11 of last year?” Sherman asked.

“It was a very big incident, but I don’t remember the details,” Rushton Sr. replied.

After he was excused, Rushton Sr. paused at the defense table and hugged Michael.

“I love you,” Michael told him.

The Moxleys were already stung by what they viewed as a betrayal on the part of their onetime neighbor, Ix. John Moxley suggested to reporters that Rushton Sr. was furthering a shameful charade.

“I think he’s crazy like a fox,” John said. “Rush Skakel drives his own car and keeps his own checkbook. If he’s incompetent, why would you let him drive?”

After a month of testimony came the closing arguments. The prosecution went first, with Benedict noting that the tree Michael said he had perched in outside the Moxley’s house was so spindly as to be “unclimbable by a human being.” Benedict suggested that if Michael climbed any tree at all, it was the one under which the body was found. The prosecutor went on to describe the savagery of the attack.

“Hitting Martha in the head so many times with a golf club that we really can’t get an accurate count,” he said. “The act of stabbing her through the neck from one side to the other with a piece of broken shaft quite frankly is the most emphatic evidence of pure hatred, rage and intent to kill.”

Benedict showed the jury a photo of Martha’s body at the crime scene and suggested that two bloody smears on her thighs came from when the killer masturbated. Bennett suggested that the killer “administered the ultimate and sickest of humiliations” and ejaculated on her, creating a need to explain the presence of his DNA when technology made such determinations possible. He regretted that Dr. Elliot Gross, the forensic pathologist who conducted the autopsy, had only fluoresced for semen around the pubic area and not the thighs.

“Dr. Gross in 1975 not having heard the word masturbation,” the prosecutor noted. “That doesn’t come up until 1992 or thereabouts.”

Benedict contended that such a frenzied killer could not possibly have appeared in the Skakel house minutes later “without a drop of blood on his clothing, without a hair out of array,” as was Littleton around 10 p.m. when Julie saw him in the kitchen, and as was Tommy around 10:20 p.m. when Littleton saw him in the master bedroom. Benedict described Littleton as “psychologically fragile” and “the defense culprit of choice,” targeted as a scapegoat after decades of cover-up.

“The defense in this case clearly began on October 30, 1975 with the disappearance of the golf club, the shaft and any other evidence that would have pinpointed the defendant to the crime,” he said.

A photo from the trial evidence of the Michael Skakel vs. the State of Connecticut case, of golf club shaft and leaves.

GettyBenedict suggested that the supposed cover-up extended to the alibi that he described as “the cornerstone of the defense.”

“You can accept the alibi at face value and still convict the defendant but of course you will want to take a careful look at that alibi,” Benedict said, “You will want to see how it was produced.”

Benedict went on, referring to a trip the Skakel brothers and a Terrien cousin took to Windham later on the day the body was discovered.

“Somebody had the bright idea to get the players out of town in the immediacy of the investigation on October 31,” Benedict said. “Not until after the return from Windham did the alibi come up.”

The implication was that the Skakels had cooked up the alibi. Benedict alluded to what Michael had supposedly said about his immunity from consequences because he was a Kennedy. But the prosecutor did not actually speak the name, saying only, “The spoiled brat smugly boasted, ‘I can get away with anything.’”

Benedict ended by saying that the Skakel family’s purported contrivances had only strengthened the case against Michael and that his guilt had been proven “beyond a reasonable doubt,” that phrase being the prosecutor’s final words before it was Sherman’s turn.

Sherman now sought to convince the jury otherwise, but he never explicitly used the words “reasonable doubt” and never told the jurors that if they harbored any, it would require them to acquit his client.

Sherman did begin by noting that ”one Skakel or another” had been a suspect in the case for nearly three decades.

“But you know folks, that’s not good enough,” Sherman said. “They have to be a little more specific than that.”

Sherman reminded the jurors that the Greenwich police had sought to arrest Tommy early on, only for the prosecutor to say there was insufficient probable cause.

“This is investigative musical chairs and unfortunately for Michael Skakel, when the music stopped he got caught in that chair over there,” Sherman said.

Sherman meant the seat at the defense table.

“But he wasn’t the only one they were investigating, obviously,” Sherman said.

Sherman seemed as if he might go ahead and present Tommy as an alternative suspect for the jury to consider. But he instead continued to concentrate on Littleton, contending that the tutor’s confession was “no less compelling” than Michael’s supposed admissions to having been at the scene of the crime.

Sherman sought to bolster Michael’s alibi, suggesting that Andrea Shakespeare had previously been less certain that Michael had remained behind. He also reminded the jurors of the beatings and hazing at Elan. He suggested that the witnesses to the supposed confessions were influenced by reward money and personal animosity as well as a desire to be part of a big drama. He noted that Coleman had been high on heroin while testifying at the preliminary hearing. He branded the supposed remark about being a Kennedy as a clear lie.

“I don’t buy it and I don’t think you will, too,” Sherman said.

Sherman told the jury not to forget that at other times the authorities had considered Tommy Skakel and Ken Littleton leading candidates to be seated at the defendant’s table.

“They have had 27 years to put someone in that chair,” Sherman said. “They tried it out a couple of times; it didn’t work.”

He reminded the jurors of when the prosecutor’s office had declined to approve an arrest warrant for Tommy.

“They said, no, it’s not enough” Sherman went on. “Well, now it’s your turn. They are coming to you with something and it’s your turn to say, it’s not enough. It’s not acceptable. There are too many questions.”

He was not pointing a finger at Tommy as a possible killer. He was saying that the police had been wrong about Tommy and were now wrong about Michael.

“They put a new sticker on that Tommy Skakel warrant and they put Michael’s name on it,” Sherman declared.

Sherman was essentially seeking to acquit both Skakel brothers, which would be a huge double victory for the family that retained him. He even went to far as to suggest there was not enough to convict Littleton, either.

“The state attorney’s office is being comforted by the fact that they didn’t make the wrong decisions by arresting Ken Littleton or by arresting Tommy Skakel,” Sherman said. “You shouldn’t have that same feeling of nausea that maybe you made the wrong decision in finding Michael Skakel guilty of this murder based on the evidence that was presented to you.”

With a “thank you very much,” the defense then rested. But under Connecticut law, the prosecution gets another turn. Benedict returned to the question of the alibi, suggesting that in whisking the older boys and their cousin away to Windham, the family had not been seeking to protect them from the media or anything else, as the younger Skakels and Julie were left behind.

He described “father Skakel,” leading the older boys and the cousin “almost like leading the Von Trapp family over the Alps” to give statements at the Greenwich police station two weeks later.

“He scripted or rehearsed a group of alibi witnesses,” Benedict said.

As for the absence of forensic evidence, Benedict noted that it has to be recovered in the first place, and the Skakel home had still not been searched 36 hours after the murder, allowing plenty of time to dispose of anything incriminating. Benedict proposed that the very absence of the golf club grip and its presumed identification band was itself physical evidence, for nobody other than a Skakel would have had reason to dispose of it.

Benedict said that the jury should discount Tommy as a suspect, most particularly if it accepted that the murder had indeed occurred around 10 p.m. Benedict contended there was no evidence at all pointing to Littleton, noting that the supposed confession was part of a police set-up and deemed bogus by seemingly everyone save maybe Sherman.

“Counsel seems to have the impression that Ken Littleton confessed,” Benedict said.

Benedict defended the testimony of the former Elan residents who testified that they had heard Michael confess. He sought to frame one statement in particular in a way to make it more believable, noting that it had been made just after Michael had been dragged back to Elan after escaping and was about to face a punishing “general meeting.”

“Is it surprising then that in that setting this spoiled brat would boast to the person supposed to be guarding him, no problem, I can deal with this, saying in teenage bravado, yeah, I can get away with murder, I am related to the Kennedys, I did beat my neighbor with a golf club to death, my family has got me here to keep me away from the police?” Benedict said.

The prosecutor went on, “Ladies and gentlemen, that was not beaten out of the defendant. That was simply teenage impulsiveness letting loose his tongue.”

Benedict observed that the witnesses who reported Michael making incriminating statements had come forward independently.

“It’s not like they were marched down to the Greenwich police station by dad,” Benedict said.

A Skakel family photo from the trial evidence of the Michael Skakel vs. the State of Connecticut case is shown on May 22, 2002. (From top) Michael’s father, Rushton Skakel, his brother Rushton Jr., his sister Julie, his brother Thomas (second boy without shirt), and Michael (below Thomas, left). Others are unidentified.

GettyBenedict contended that Michael’s very presence at Elan was part of a cover-up extending to Julie’s testimony that being caught with his mother’s dress was what had led Michael to bolt from the car on the bridge, shouting he had done something terrible and had either to kill himself or get out of the country.

“People feel the need to get out of the country when they want to avoid the police,” Benedict observed.

Benedict proceeded to Michael Skakel’s book proposal, in particular his taped narration of the night of the murder, which the prosecutor termed “as transparent, contrived [and] inept a tale as can be told.” Benedict contended that the passage in which Michael describes his return from his cousin’s housecontains “the fact that gives lie to the whole alibi.” Benedict played a two-minute except of the 32-minute tape and a partial transcript was projected on a screen as Michael’s voice filled the courtroom.

“Anyway, we got home and all the lights, most of the lights were out, and I went walking around the house. Nobody was on the porch, um, went upstairs to my sister’s room. Her door was closed, um, and I remember that Andrea [Shakespeare] had gone home.”

The projected text vanished for an instant and then reappeared, with “and I remember that Andrea [Shakespeare] had gone home” in a larger font and red letters, the rest of the excerpt in smaller, black letters. Benedict stopped the tape and reminded the jury that the Lincoln had left for the cousin’s house before Julie took Andrea home.

“Somebody who had actually left already would have no idea of Julie’s trip to take Andrea home,” the prosecutor said. “On the other hand, the [figure who heard] ‘Michael come back here’ as he ran past Julie as she exited the house would have been fully aware of this fact.”

Here was what really did seem to be a Perry Mason moment. Benedict then played a second two-minute excerpt, in which Michael described being unable to sleep and deciding to head out into the night. His recorded voice was again accompanied by a partial transcript on the screen.

“I said, ‘Fuck this, you know, why should I do this, you know, Martha likes me, I’ll go, I’ll go get a kiss from Martha. I’ll be bold tonight.’ You know, booze gave me, made me, gave me courage again.”

Benedict paraphrased what Michael had told the ghostwriter happened next.

“And then, the defendant does the most amazing thing․ He takes us on this staggering walk down memory lane. He first avoids the driveway oval where the club head was found and, more likely, [where] he first caught up with [the victim], given [Henry] Lee’s testimony about blood in the driveway where the whole terrible thing started. Then he has himself under a streetlight throwing rocks and yelling into that circle with the exact same motion that had to have been used to beat [Martha] to death.

The prosecutor posed a question.

“Why this explanation? It’s kind of obvious.”

The prosecutor suggested that Michael himself had given the answer to the ghostwriter.

“As he explained… what if somebody saw me last night? And then… ”

With a showman’s timing, Benedict played a third two-minute section of the tape, also accompanied by a partial transcript.

“I went to sleep, then I woke up to [Dorothy] Moxley saying ‘Michael, have you seen Martha?’”

At that instant, a photo of a smiling Martha appeared in the lower right corner of the screen. New text appeared as the tape continued.

“I’m like, ‘What?’ And I was like still high from the night before, a little drunk, then I was like ‘What?’ I was like ‘Oh my God, did they see me last night?’ And I’m like, ‘I don’t know,’ I’m like, and I remember just having a feeling of panic.”

A different photo of Martha appeared, the crime scene photo of her battered body under the pine tree. This photograph then vanished and more transcript appeared in pace with Michael’s amplified narration.

“Like ‘Oh shit.’ You know, like my worry of what I went to bed with, like, maybe, I don’t know, you know what I mean? I just had, I had a feeling of panic.”

A third photograph, also of the body at the crime scene, appeared beside the text. The tape playback stopped and the prosecutor continued.

“How could the sight of Dorothy Moxley possibly produce a feeling of panic in an innocent person, in a person who had gone to sleep knowing nothing of [the victim’s] murder?” Benedict asked. “The evidence tells you that only a person who had experienced that poor girl lying under the tree, not in his dreams but first-hand, would have a cause to panic on awakening that morning.”

The overall effect of the multimedia presentation was to make supposition seem more concrete, to make theory seem more like fact, all of it narrated by the defendant himself. The goal was for the jury to reach the conclusion required for a conviction that few had thought possible.

“He murdered Martha Moxley beyond every reasonable doubt,” Benedict closed by saying.

Benedict had repeated those words, “reasonable doubt,” that Sherman had not uttered at all.

The prosecutor’s final argument was widely described as one of the most effective in memory—but most observers still felt sure that Michael would be acquitted. One suggested that the only reason the jurors had not returned a verdict by the end of the first day was that they did not want to look like their counterparts in the O.J. Simpson trial, who had taken only an hour to come back having found him not guilty.

With the apparent expectation of a favorable verdict, Tommy Skakel made his first appearance in the courtroom as the jury deliberated his brother’s fate. Robert F. Kennedy Jr. was also there, as was the Skakel family lawyer who had hired Sherman. An acquittal would have made for a win-win, Michael and Tommy leaving the courthouse together as if they had both been cleared.

But the jurors kept deliberating through that day and on through the next. The testimony they asked to hear read back was that of Andrea Shakespeare, who had called into question Michael’s alibi that the prosecutor suggested was part of a family-orchestrated cover-up.

The jurors had no way of knowing that Sherman had failed to track down and present an independent witness who would later unequivocally affirm that Michael had indeed been at his cousin’s house that night. This assertion would have in turn challenged the prosecution’s suggestion that the alibi was part of a collective effort by the family to help Michael get away with murder.

At 10:40 a.m. on the fourth day, the jury sent out a note that it had reached a unanimous determination. Martha’s mother, Dorothy, and brother, John, watched the six men and six women file into the courtroom. The foreman, Kevin Cambra, proprietor of a driver’s education school, announced the verdict.

“Guilty.”

The sound that filled the courtroom would later be described as a collective gasp.

“I’d like to say something,” Michael Skakel told the judge.

“No, sir,” the judge said.

The judge then announced, “Bail is revoked. Take the defendant into custody.”

Michael was cuffed and led away by a trio of court officers. One of them pushed away David Skakel’s hand as he reached out to touch his brother.

David had brought a statement that he had written with the apparent expectation that Michael would be acquitted. He read it to the assembled press.

“Martha’s short life and the manner of her death should never be forgotten,” he said. “For our family, grieving has coincided with accusation. Michael is innocent. I know this because I know Michael, like only a brother does. You may want finality to this tragedy, and our family wants the same, as much as anyone. But truth is more important than closure.”

Martha’s mother had also written something, but she had not dared to anticipate this outcome.

“I wrote a little prayer and it started out, ‘Dear Lord. Again today like I’ve been doing for 27 years, I’m praying that I can find justice for Martha,” she told the press.

She went on, “This whole thing was about Martha. I feel so blessed and so overwhelmed. This is Martha’s day. I hope people remember that.”

She and her son then drove in her Mercedes up to Plymouth Cemetery. They visited the adjoining graves of Martha and her father, David, who had died from a heart attack in 1988 at age 57, arguably also a murder victim, having pent in his shock and grief over her death.

Green carnations lie on the grave of Martha Elizabeth Moxley at Putnam Cemetery in Greenwich, Connecticut, March 22, 2000.

Craig Ambrosio/Liaison via GettyAt the sentencing on Aug. 28, 2002, Dorothy Moxley reasoned it was only fair for Michael to receive a life term.

“Michael Skakel sentenced us to life without Martha,” she noted.

Of her daughter, the mother said, “For years I prayed that she did not see the first blow from the golf club coming, and that she died immediately after that first blow. I now know that isn’t the way it happened. I know now that she must have been very frightened and suffered a great deal.”

When his turn came to speak, a sometimes-tearful Michael made a bid for sympathy, describing a poverty of a different kind amidst wealth and social prominence.

“Love was not something in my family,” he said. “There was lots of hardship and an enormous amount of pain.”

His poor little rich boy appeal was backed with filings by his lawyers. They described Michael’s father as a man who had been given the helm of the family business, Great Lakes Carbon, after his parents and older brother, George, died in plane crashes, but had lacked the necessary “skill and talent.” Rushton Skakel Sr. had been left “exceedingly unhappy,” though this business disappointment was “nothing compared to the pain he suffered when his wife died of cancer.” He was left without his “emotional compass,” and fell into alcoholism, which “exacerbated his abusive behavior toward his children,” causing him to burn Julie with matches as well as beat Michael with a hairbrush and even once aim a rifle at him.

But to expect leniency, the now 41-year-old Michael would have had to accept responsibility for the crime and express remorse. He could not do that while continuing to maintain his innocence.

“I would love to be able to say I did this crime so the Moxley family could have rest and peace, but I can’t, Your Honor,” he told the court. “To do that would be a lie in front of my God who I am going to be in front of for eternity. And I have to live by His laws. And His laws tell me I cannot bear false witness against anybody or myself.”

Michael reported having a close relationship with the Almighty since Oct. 25, 1982, when God asked if he wanted to continue the way he was going into the darkness of drugs and alcohol or choose the path to hope. Michael said he had first encountered Alcoholics Anonymous just hours later and had been sober ever since. His subsequent efforts to help others become and stay sober were reported in numerous letters to the court, including one from Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and another from Ethel Kennedy, who had otherwise stayed clear of the case. Michael had been hired by a non-profit organization to spread AA to the prisons and to “the godless countries of this world.” He had since been fired and blamed the former LAPD detective whose book named him as the killer—Mark Fuhrman, who was attending the sentencing.

“I don’t have a job because this man over here, Mr. Fuhrman, wrote a book about me filled with lies,” Michael said. “Because of that man’s book, that job was taken away from me. My wife was pregnant. We lost our insurance. Oh yeah, my family had to take care of me. I had no other place to go.”

He was here addressing criticism in the pre-sentence report that he was out of work and relying on the other Skakels for support.

He was here addressing criticism in the pre-sentence report that he was out of work and relying on the other Skakels for support.

“And as far as a job is concerned I mean, what did Jesus Christ do?” Michael said. “He walked around the world telling people he loved them. Should he go to jail for that? Was he a bad person for that?”

He spoke of his son, George, who was now three.

“My son told me on Easter, ‘Dad, mom says you are going to prison and that only bad men go to prison.’ And I said, ‘Sweetie, today is Easter. It’s about Easter eggs and going to dinner with family. But it’s really about the best kid that ever came to this place in the whole world was God’s child and they put him in prison.’”

Michael continued. “And he said, ‘They did that?’ And I said, ‘Yeah.’ And he says, ‘Well, let’s go play in the sandbox then.’”

Michael went on to suggest that he now faced sentencing by Judge John Kavenewsky much as Jesus had by Pontius Pilate. Michael said he had a message to the court from God.

“And I stand here before you today with my life in your hands and the good Lord tells me to tell you that in 2,000 years this place hasn’t changed a bit, that you still want to let Barabbas go, that I am innocent as charged,” Michael said.

Michael had his scripture a touch confused, as it was the crowd that chose Barabbas to be the prisoner freed at Passover time in keeping with local tradition and it had nothing to do with anybody’s innocence.

“But I am also in this court of law, and whatever sentence you impose on me I accept in God’s name,” Michael now said.

He then spoke again of his son.

“I can’t even look at the picture of him sometimes,” Michael said. “When that boy was born, it was the most amazing thing in the world to me. Every second of very day I look at that child and I just say, ‘If you don’t believe in God, have a child.’ God gave me that boy.”

More than one person in the courtroom considered how different things would have been if Rushton Sr. had felt even an approximation of this regarding his children.

“He says the most amazing things,” Michael went on about his son. “The week before I came here, in bed he said, ‘Dad, before you go in front of those bad men in Connecticut, I want you to be peaceful.’”

Michael said that he and his wife, the niece of family lawyer Tom Sheridan, were now divorced. The boy needed his father more than ever.

“Have mercy on him,” Michael asked the judge.

Michael closed by saying that he prayed for “this whole court,” as well as the Moxley family and the prosecution, even the press.

“Because that’s what God tells me to do,” he said.

The judge began by saying that he would not overlook Michael’s age at the time of the crime.

“He was barely 15,” the judge said.

There was also what the judge termed “his dysfunctional upbringing.”

“But in the court’s view, mitigation only carries the defendant so far in this case,” the judge went on. “I won’t claim to know for certain what prompted or caused the defendant to kill Martha Moxley but by the evidence delivered I do know that for the last 25 years or more, well into his adult life, the defendant has been living a lie about this guilt. The defendant has accepted no responsibility, he has expressed no remorse.”

The judge made clear that he was considering Michael as an individual and not as a member of a clan or as anything else.

“I want the defendant to be assured, though, that my focus is on him today and only him and nobody else,” the judge said.

And whatever redemption Michael may have found, the judge considered him to be ultimately unrepentant. The judge ordered him to rise.

“Michael Skakel, for the crime of murder, you are sentenced to the custody of the commissioner of corrections to a term of not less than 20 years nor more than life.”

Three months later, on Jan. 2, 2003, Rushton Skakel Sr. died in his home in Hobe Sound, Florida. The funeral was at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Greenwich with nine priests in attendance. Prison officials did not permit Michael to go, but his young son, George, was there. The program said Tommy was to read from the Book of Wisdom, but Rushton Jr. actually stepped up when the moment came.

Another brother, John, gave a eulogy, saying at one point, “In his last years, he faced the indignity of having his son wrongly accused. He chose not to get down on the level of those who had attacked the family.”

That same month, The Atlantic published a 15,000-word article by Robert F. Kennedy Jr. titled “A Miscarriage of Justice.” Robert Jr. and Michael had become estranged after the scandal involving the other Michael and the teenaged babysitter. But Robert Jr. had since visited Michael Skakel in prison and resolved to champion his cause.

“The tragedy of Martha Moxley’s death, twenty-seven years ago, has been compounded by the conviction of an innocent man,” Robert now wrote.

Robert went on to say, just as he had in the pre-sentencing letter, “I know Michael Skakel, my first cousin, as well as one person can know another. He helped me to get sober, in 1983. We attended hundreds of alcoholism-recovery meetings together. In that context and others we have shared our deepest feelings. For fifteen years we skied, fished, hiked, and traveled together, often with my wife and children. During that time I sometimes spent as many as two or three weekends a month in his company. Like nearly everyone else who knows him well, I love Michael.“

Robert blamed their estrangement in 1998 not on the Kennedy clan’s behavior during the babysitter scandal but on “stress from the public focus on Michael as a murder suspect” that “began to affect his personality.”

“He lashed out at the Kennedy family, which he believed was partly responsible for his predicament, and refused to speak to me,” Robert wrote. “On the two days I attended his court proceedings last year, in Norwalk, Connecticut, he was cold and distant.”

Nevertheless, Robert said, “I support him not out of misguided family loyalty but because I am certain he is innocent.”

Robert seemed to feel he was saying nothing remarkable when he proceeded to report that the Skakels “rarely discussed the Moxley case among themselves… because of family culture and legal advice.” He quoted Julie as telling him, “We never talked about it. Through all the years we never discussed this. We never compared notes.”

A 15-year-old neighbor who was last seen with Tommy was murdered with a golf club that almost certainly came from their house and they never felt compelled to discuss it? If nothing else, to jog each other’s memory for something that might help them catch the killer?

Robert’s failure to see anything psychically askew here makes it seem that in this regard it is not so much that the Skakel kids are Kennedy cousins as that Robert is a Skakel cousin.

Family portrait of Ethel Kennedy (nee Skakel) and her husband, American politician Robert F. Kennedy, and their children and dog, in their home, McLean, Virginia, March 1958. Ethel was the sister of Rushton Skakel Sr.

Ed Clark/Getty/Ed Clark/Getty“Michael’s conviction shocked his six siblings into talking about the case with one another, and with me,” Robert wrote. “For the first time, they shared their memories of the night when Martha Moxley was killed.”

Robert reported that he spoke to each of his cousins as well as Michael’s lawyers and to investigators. He also studied the police reports and news accounts and “put together the story for myself.”

He then recounted the details of the night of the murder—including that, “after the other boys left, Tom had a ‘sexual’ encounter with Martha that lasted twenty minutes, ending in mutual masturbation to orgasm.”

“Around 9:50 the two rearranged their clothes, and Martha said good night. Tom last saw her hurrying across the rear lawn toward her house to make her curfew.”

Robert did not address the question of whether the tree near John Moxley’s window could have supported Michael. But Robert did put Michael’s reason for having initially lied about his movements that night in a context that made it seem plausible.

“As Jay Leno suggested, referring to the Skakel trial, many people would rather be found guilty of murder than be suspected of masturbating in a tree,” Robert noted.

Robert also insisted that Michael “did not invent the story in the early nineties for his Sutton [Associates] interview” and “has been telling it consistently for at least twenty-three years.” Robert said Michael gave this account to an aunt who was a former nun in 1979 and to his psychiatrists in 1980 and “to many friends before the 1990s.”

“I heard him tell it several times, beginning in 1983,” Robert said.

(A reader might be puzzled here, as Robert had said that the Skakels never discussed the murder among themselves. It would seem that Michael told the story to many friends, an aunt and Robert, but not to his siblings.)

Robert claimed he had told the defense attorney Sherman “several times during the trial that I would testify about Michael’s pre-Sutton recounting, but I was never called.” Robert did not seem to consider that Sherman might have worried that putting a Kennedy on the stand might have added credence to the junkie Coleman’s claims and made the jury think, “cover-up.”

Robert also reported that Rushton Sr. had Sutton Associates reinvestigated the case because “the Skakels were convinced that the original police investigation had been bungled, to Tom’s detriment, and they were desperate to clear the family name.”

“Both Tom and Michael told Sutton detectives details they had not disclosed to the police in 1975,” Robert allowed. “Tom, for example, described his sexual encounter with Martha on the rear lawn of the Skakel property.”

Robert said that he asked Tommy “why he had waited so long to tell the full story” and that “I anticipated his answer—Rushton’s severe attitude toward sex.”

Robert reported that the Skakel kids had told him that Rushton Sr. “considered masturbation ‘equivalent to the slaughter of millions of potential Christians.’” Robert quoted Tom as saying, “I loved my father and didn’t want to lose his respect. My father was the most important person in my life. He was a staunch Catholic with strict views about premarital sex. I was frightened of disappointing him.”

Robert cited the same reason for Michael having changed his tale, adding that Michael was “the runt of the family” and had “always been a target for his father’s anger.” Robert went on to say, “Rushton Skakel drank alcoholically for four years following his wife’s death. (He quit drinking in 1977.) During this period he occasionally hit Michael, and once fired a gun in his direction during a hunting trip. Michael sometimes slept in a closet to escape his father’s wrath. When Michael was ten, Rushton had caught him looking at Playboy with his friends and knocked him silly. By age thirteen Michael was an alcoholic.”

Robert said that at the time of the Sutton questioning, Michael was “no longer fearful of his father” and “Michael, too, told Sutton detectives the full story of what he had done that night.”

Robert further proposed that young Michael, as “a scrawny kid,” lacked the strength to have administered blows such as killed Martha.

In recounting the murder, Robert stated as fact certain details that some investigators still questioned. He said that “using evidence from the autopsy, the police determined that the murder took place at around 10:00 P.M.” The timing would seem to clear Michael given the alibi corroborated by the uncalled witness.

In truth—as was made clear during the trial—the police never felt able to determine the time of the murder based on the autopsy any more precisely than sometime between 9:30 p.m. and 5 a.m. The prosecution’s belief that she was likely killed around 10 p.m. was based to a significant degree on the barking of the dogs and the absence of any subsequent sightings of Martha. But the police never considered that proof.

Robert failed to mention Tommy’s lie to his sister and to Mrs. Moxley when Martha was still missing that he had gone in to do a (nonexistent) school project on Lincoln logs. The cops understandably took such a highly specific and otherwise unnecessary lie to be an indication that Tommy knew Martha had been murdered.

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. (R) and his brother Douglas Kennedy (L) depart the Fairfield County Courthouse during the lunch break of Michael Skakel’s pretrial hearing in Stamford, Connecticut.

ReutersAnd while he noted that Murphy and Krebs of Sutton Associates both told him they believed Michael was innocent, Robert was either unaware of, or simply failed to mention, something vital: Murphy and Krebsbothbeleived that Tommy was at one critical moment on the verge of confessing to the killing .

Having dismissed his cousins Tommy and Michael as possible suspects, Robert then spent more than 3,000 words detailing why he believed that the tutor Littleton might be the killer. He reported towards the end of this long argument that, “In July of 1999 Littleton called the Greenwich Time from McLean Hospital and said that the Kennedy family was trying to kill him.”

“Shortly after being released, he stabbed himself four times in the chest with a kitchen knife,” Robert went on to report. “The police who searched his apartment found the charred pages of a diary, torn from the binding and burned. Littleton refused to talk with the police about the stabbing.”

Robert said at the start of his piece that Michael suffered a personality change and became paranoid about the Kennedy family as a result of being under suspicion, but he seemed not to consider that the same might have been true for the already unstable tutor.

In any event, it could not have helped Littleton’s mental condition to have an actual Kennedy writing an article all but accusing him of being the killer.

“I do not know that Ken Littleton killed Martha Moxley,” Kennedy hedged, taking a quarter-step back from accusation. “I do know—and as a former prosecutor, I understand the laws of evidence—that the state’s case against Littleton was much stronger than any case against Michael Skakel.”

Robert took issue with the state’s tactics, describing Frank Garr as being overly aggressive in lining up witnesses who had been at Elan with Michael, including a former resident named Diana Hozman. Robert said that Hozman told him she had initially contacted Garr hoping to help exonerate Michael.

“She said that she thought Garr was bullying and pressuring her into saying that Michael had confessed. ‘I felt they were desperate to blame Michael,’ she told me. ‘Garr took everything I said out of context to make it fit into his puzzle. He definitely didn’t want to hear anything good about Michael. I’m sorry I even talked to Garr.’”

Robert added that Hozman had been slated to testify for the prosecution, but had continued to voice doubts that Michael had actually confessed.

As he began to address the witnesses from Elan, Robert revealed all the more why he had particular sympathy for Michael. Robert wrote, “Every Kennedy is painfully familiar with the attention seeker who fashions a chance encounter with a celebrity into a disparaging anecdote. Michael’s notoriety made him a magnet for such people—and a February 1996 television program helped prosecutors corral a group of them.”

Robert was effective in knocking down the two key Elan witnesses, Higgins as well as Coleman, who testified that Michael had said he would get away with the murder because he was a Kennedy.

“A phrase no Skakel would be caught dead saying,” Robert noted.

And Coleman wasn’t the only one playing up the Kennedy connection, Robert charged.

“The writer Dominick Dunne” was “a driving force behind Michael Skakel’s prosecution” and “continually accused the Skakel family of using its power and Kennedy connections to intimidate the Greenwich police ‘to protect one of their own,’” Robert wrote.

He quoted a 1991 Vanity Fair article in which Dunne wrote, “It is thought in the community and elsewhere that Kennedy influence was brought to bear.”

Dunne had further insisted in 2000 that “the Skakels were able to hold off the police all these years… If this was a family of lesser stature, that simply would not have happened.” Robert noted that the police were in fact permitted to interview all the Skakels and without benefit of counsel and that the family did not lawyer up until three months after the killing. He also observed that Tommy took multiple lie detector tests (though he failed to report that after being found truthful in them, Tommy changed his story) and that various Skakel children agreed to be hypnotized. They also consented to being questioned while under sodium pentothal, the so-called truth serum.

On top of that, Robert cited a New York Daily News article in which a Greenwich detective was quoted saying that early on Rushton Sr. “was so cooperative and there was the feeling no one there could have done it.” Robert also cited Lenny Levitt’s remark that in the early days of the case, “There was no cover-up. There was a screw-up.”

But Robert ignored or perhaps simply did not understand that the screw-up began with the failure to conduct an immediate search of the Skakel house, as the police did of the home of the equally cooperative Yale grad who was deemed to be “odd.”

Perhaps for the very reason that he really is a Kennedy and knew the actual gulf that existed then between his family and the Skakels, Robert failed to grasp the initial effect the association with his surname must have had on cops and just about everybody else.

What Robert did know from his own experience was that a Kennedy association can swiftly turn into a liability once the initial deference is dispelled. And officials who regret having been slow to act can suddenly become determined to resist any cover-up, whether or not one has been attempted or even contemplated.

Indeed, at least some of the cops on the case soon took a different view about the possibility of a Skakel being the killer. And, rather than benefit from his family’s supposed power and influence, Tommy had become the leading suspect—which Robert saw as evidence of cops with tunnel vision.

Robert quoted Browne, the state’s attorney who rejected the police application for an arrest warrant for Tommy, as telling him, “There was nothing in there other than the fact that he was the last to see her alive and that he’d had some mental problems in the past.”

Robert argued that it was not the Skakels, but Dominick Dunne who wielded undue influence over the police and was the reason “why, after years of uncertainty and inaction, Connecticut officials decided to pursue Michael with sudden ferocity.”

Robert said that Dunne “had personal reasons for his attraction to this case,” noting that the writer’s daughter, Dominique, was murdered in 1982 and that the restaurant chef convicted of the killing was freed after less than three years. Robert quoted Dunne as saying in 1996, “I was so outraged about our justice system that everything I’ve written since has dealt with that system—how people with money and power get different verdicts than other people.”

Robert went on, “Dunne has built his career on linking notorious murders to powerful people, including John and Patsy Ramsey, Claus von Bulow, and O.J. Simpson. That formula has given Dunne his own measure of celebrity and wealth. His efforts to connect a Kennedy relative to the Moxley murder have been both a decade-long fixation and a profitable venture.”

Robert charged that “Dunne ignored the strong evidence against Littleton… at least partly because if it didn’t turn out that a Kennedy cousin had committed the crime, the story would be worth much less to Dunne.”

Nobody who knew Dunne would likely contest that he was overly fascinated with the rich. His imaginings in this regard could indeed skew his reporting, but his daughter’s death had made him only more devout in his belief that everybody deserves justice. He would never have hoped for somebody to be unfairly accused. And to suggest he might have done for so the sake of monetary gain is no less outrageous than anything he might have ever claimed about the Kennedys and the Skakels.

Nevertheless, Robert contended that Dunne recruited “his friend Mark Fuhrman” to be “the Torquemada” of the Greenwich police with “a 283-page diatribe” castigating the cops “as ‘servants of the rich and powerful.’”

Robert said that, like Dunne, Fuhrman “had apparently decided before he began his investigation that the killer must be a wealthy, powerful celebrity who had corrupted the police.” Robert quoted Fuhrman as saying of the tutor, “Littleton had no money, no powerful family behind him, no clout. If Littleton had murdered Martha Moxley, he would not have gotten away with it.”

Robert then turned prosecutorial on the prosecution. He charged that Fuhrman’s book “lit a fire beneath Connecticut law-enforcement officials,” prompting the convening of a grand jury two months after publication and triggering “a multimillion-dollar effort to convict Michael Skakel.” Robert noted that the cover of the paperback Murder in Greenwich billed itself as “the book that spawned the Connecticut grand jury investigation.” He cited Dunne’s contention in Vanity Fair that, “I firmly believe Murder in Greenwich, for which I wrote the introduction, is what caused a grand jury to be called after 25 years.”

Robert became as conspiracy-minded as Dunne ever was, only imagining not a cover-up, but rather a set-up.

“Why did they give [Littleton] immunity?” Robert asked. “The state might have concluded that a prosecution of Littleton—especially if it failed, and any prosecution twenty-three years after the crime stood small chance of success—would not end the public debate over their competence and integrity but instead would inflame Fuhrman and Dunne, who had already accused the police of giving the Skakels a pass by making Littleton the fall guy. The only way to still the criticism was to prosecute a Skakel.

“And they would need Littleton to testify without taking the Fifth—an action that might suggest to the jury that the witness rather than the defendant was guilty. The only way to compel Littleton to testify was to first grant him immunity. The case against Michael was weak, but by indicting a Skakel investigators could at least quiet Fuhrman’s charges that they were ‘sycophants’ and ‘cowards.’ Dunne had already sent signals that his objectives would be satisfied short of a conviction, as long as Michael was indicted. ‘I just want to see this guy with handcuffs—humiliated,’ he told [the CNN program] Burden of Proof.”

At one point, Fuhrman had reported that the prosecution intended to use his Murder in Greenwich as a “blueprint.” Robert now added, “In fact, the state followed the book practically line by line.”

In actual fact, Garr had long since come to believe that Michael was the killer and had pressed the prosecutor to convene the grand jury before the publication of Fuhrman’s book lest anyone think what Robert was now contending.

Robert went on to charge that the prosecutors were “taking their cue from Fuhrman” when they argued that Michael had killed Martha in a rage fueled by booze and jealousy. Robert quoted Michael telling him during a prison visit, “I never knew about Tom and Martha until I heard it on TV in 1998.”

That was five years after Tommy told his new version of events to the Sutton investigators.

“Michael’s problems were aggravated by an overconfident and less than zealous defense lawyer who seemed more interested in courting the press and ingratiating himself with Dominick Dunne than in getting his client acquitted,” Robert wrote.

Robert suggested that Sherman could have prevented a trial in the first place by filing a preemptive appeal arguing that at the time of the murder the statute of limitations in Connecticut was five years—but failed to do so because it “would have deprived Sherman of the nationally publicized trial he expected would boost his career.”

Sherman had blithely allowed a cop and someone who had a friend in common with the Moxleys to be seated on the jury. Robert also said that the Skakel family “was distressed by Sherman’s seeming lack of attention to the trial, what they saw as his failure to prepare them adequately before their testimony, and his undisguised friendship with Dominick Dunne.” He further reported that “on at least one occasion Sherman arrived at court in a limousine with Dunne; he spent at least one evening at Dunne’s house, at a party.”

So why did the family stick with Sherman after his initial charm wore thin and his confidence came to seem a form of blindness?

“We’d already paid Mickey a million dollars, and at that point it was too much,” Julie later said by Robert’s account.

Robert suggested that “perhaps in recognition of Dunne’s solicitude toward Ken Littleton,” Sherman refused, by Julie’s account, “to allow her or the other Skakels to testify about the strong evidence against Littleton,” whatever that supposed evidence may have been. Robert said that when he queried Sherman, the lawyer said of Littleton, “He’s a pathetic creature. I don’t want to look like I’m beating up on him.”

Robert also thought Sherman missed an important opportunity when the state’s attorney investigator, Jack Solomon, was on the stand. Solomon had long been the biggest believer in Littleton’s guilt and Robert noted that the investigator had a three-ring binder with “three decades’ worth of police information” about the tutor, “along with a summary of the state’s case against him.”

“That information might have proved critically valuable to Michael’s defense,” Robert said. “Sherman did not have the binder marked as an exhibit or placed in evidence.”

Solomon was also the one who contrived to get Littleton’s ex-wife to make the tape that Sherman sought to pass off as a confession. The binder was said to include details of other murders that Solomon sought to tie to Littleton on a far-fetched hunch the tutor was possibly a serial killer. Sherman might well have worried that the binder would make Solomon look too much like an obsessed cop fixated on a suspect beyond the bounds of reason.

There was little disputing Robert’s contention that that Sherman was less than masterful in cross-examining Andrea Shakespeare. She had called Michael’s alibi into question by testifying under direct examination by the prosecutor that she was “under the impression” that he did not go with the others to his cousin’s house and was still in the Skakel home when she left.

Robert now gave Sherman an added kick by noting the Skakels reported that Sherman billed them $150,000 for media appearances.

“The public’s impression of Michael Skakel couldn’t have been more negative,” Robert said. “Given the gift that every great defense lawyer yearns for, a genuinely innocent paying client, Sherman squandered a fortune and sacrificed Michael on the altar of his ego.”

After his defense of Michael was published in The Atlantic, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. received a letter from someone named Crawford Mills, who had grown up near the Skakels.

Mills directed Robert to Gitano Bryant, cousin of basketball player Kobe Bryant. Gitano told Robert that he had taken a train from New York to Belle Haven with two friends on the night of the murder. Gitano further reported that his friends had spoken of “going caveman” on a girl and that one of them had become fixated on Martha Moxley after seeing her during a previous visit. Gitano said he departed before his friends, who afterwards told him they had indeed gone caveman. Gitano assumed they were speaking of Martha.

Gitano agreed to make a videotaped statement, which became part of a petition for a new trial. A Connecticut court found Gitano’s account to lack sufficient credibility. The court further ruled that other possible new evidence—including the independent witness who could have supported Michael’s alibi, other witnesses who could have impeached Coleman and a police sketch of a man seen in the vicinity of the crime scene—did not legally qualify as new because Sherman could have produced these at trial if he had been duly diligent. The alibi witness was mentioned in a police report that Sherman had been given. The sketch was mentioned in two such police reports.

The petition for a new trial was denied, as was an appeal on the grounds that the case should have been heard in juvenile court and that the statute of limitations should have precluded prosecution in any venue and that Coleman’s testimony should not have been admitted because he was deceased at the time of the trial and therefore could not be cross-examined by the defense. The Skakels retained former solicitor general Theodore Olson to petition the U.S. Supreme Court, which declined to hear the case.

Michael remained in the McDougall-Walker Correctional Institution in Suffield. He was visited regularly by his youngest brother, Stephen, who had been just 9 at the time of the murder. He was also visited by Jim Murphy of Sutton Associates. Murphy told him that he believed he was innocent, a belief that the retired FBI agent also expressed to Martha Moxley’s mother.

On what happened to be Valentine’s Day of 2012, Murphy had lunch with Dorothy Moxley and her son, John, at the University Club in Manhattan—which the Moxleys had joined after being proposed for membership by Rushton Skakel Sr. in a neighborly gesture when they first moved to Greenwich. The Moxleys had gone here for Thanksgiving dinner that first year after Martha’s murder and her father, David, had sat silent with the pent-up grief that his wife would later suggest helped kill him before he reached 60.

Michael Skakel reacts to being granted bail during his hearing at Stamford Superior Court on Nov. 21, 2013, in Stamford, Connecticut. Skakel will be released on bail after receiving a new trial for the 1975 murder of his Greenwich, Connecticut, neighbor, Martha Moxley, of which he was convicted in 2002.

Bob Luckey-Pool/GettyMurphy now told Dorothy and John that he believed Tommy had murdered Martha. Murphy would tell others that in his view, the most likely scenario was that Tommy took one of the golf clubs by the door to ward off dogs as he walked Martha home. They were in her driveway oval, the last patch of darkness before her front door, when he resumed the romantic horseplay. He took it farther than she was ready to go, particularly just outside her home. He punched her and then bludgeoned her, later returning and making sure she was dead by stabbing her through the neck with the broken golf club shaft.

Still, Dorothy and John remained convinced of Michael’s guilt when they attended his parole hearing at the McDougall-Walker Correctional Institution in Suffield in October of 2012. John had written a letter to the three-member board, essentially arguing that Michael had believed he could get away with anything because he was a Skakel.

“I believe Michael Skakel is representative of the most dangerous aspect of our society in that he was raised in an environment in which he was exposed to and at some point embraced the mind-set that the rules of our general society did not then and do not now apply to him,” John Moxley wrote. “I believe Michael Skakel and parts of his family believed then as they do now that it was and is their birth right and privilege to deal with ‘family matters’ if necessary privately, regardless of the circumstances. And, I believe that Michael Skakel’s inbred sense of self and his self-confessed quick temper will always represent a threat to society.”

Dorothy Moxley addressed the board directly.

“Martha, my baby, will never have a life,” she said.

Michael was now 52 and had been in prison for a decade. He continued to insist upon his innocence.

“I did not commit this crime,” he said. “If I could ease Mrs. Moxley’s pain in any way, shape or form I would take responsibility all day long for this crime [but] I cannot bear false witness against myself.”

The chairwoman of the board suggested that she and her colleagues were not likely to grant early release to someone who does not even own up to the crime.

“I know the best chance of me getting parole is admitting guilt in this crime,” Michael replied. “But ten-and-a-half years later I cannot do that.”

The board took little time in denying him parole and he remained behind bars as his lawyers undertook Michael’s last chance. They filed a writ of last resort in the court of last resort contending that Michael had been denied his constitutional right to competent counsel. The 68-page petition regarding Mickey Sherman’s woeful performance as defense counsel made clear that Michael’s present legal team was only interested in defending the Skakel brother it actually represented.

“Trial counsel failed to sufficiently investigate the circumstances relating to Thomas Skakel,” the document said, regarding Sherman’s handling of the case, “and the evidence of third party culpability in that he did not conduct any investigation into Thomas Skakel’s revised explanation to investigators in the 1990s that he engaged in sexual activity with Martha Moxley as he walked her home that evening, that he was known to be a habitual liar capable of elaborate deception, that he lied to police officers, psychologists, therapists, consultants, family members, friends, lawyers, and investigators about his activities with Martha Moxley on October 30, 1975, and his activities that evening.”

Judge Thomas Bishop scheduled a hearing, not on the question of whether Michael was guilty but whether he had indeed been deprived of his constitutional right to a competent defense. Michael was called to the stand to testify and be cross-examined only in that regard. He took the oath and gave his present address as the prison where he was being held

“You wanted my prison number?” Michael asked.

The odds were slim that this would cease to be his address any time in the near future, as not even one percent of the inmates who file such writs prevail. And he would seem to have even less chance, as he was not a disadvantaged defendant who had been unable to afford an expensive lawyer. His had cost well over $1 million.

But even though he faced at least as many more years behind bars as he had already spent, he was reluctant to help himself by answering any questions about Tommy.

“Do I have to say?” Michael asked.

Michael was informed that in this instance, silence was not an option and he described Tommy as a brutal bully. Michael had no such reluctance answering questions about Mickey Sherman. Michael said the lawyer was a self-described “media whore,” who would ride off to lunch in a limo with Dominick Dunne.

“I said, ‘What the hell are you thinking about?’ He’s our mortal enemy. This guy is poison,’” Michael recalled.

Michael said that said that Sherman’s idea of preparing a defense witness who had been at Elan was to take him to dinner with a group of celebrities that included Harrison Ford and Michael Bolton. Sherman had told him that the potential witness had declared in front of the celebrities that Michael had never confessed to the murder.

Michael Sherman, the attorney representing Michael Skakel in the Martha Moxley murder case, poses for a portrait Jan. 1, 2001, in Stamford, Connecticut.

Catrina Genovese/Getty“He led me to believe that these people were coming to testify on my behalf at this trial,” Skakel said.

Sherman’s own investigator, Vito Colucci, testified that some witnesses who really were going to testify for the defense had experienced difficulty even getting the lawyer on the phone and were never adequately prepared for trial. Colucci said that he had tried in vain to get Sherman to speak to Rochester detectives who would have called the character of the prosecution’s star witness, Coleman, into serious question. Colucci noted that Sherman had previously been “a very good and diligent attorney,” but had become obsessed with celebrities and dazzled by the limelight.

“Can I say Hollywood?” Colucci asked.

Sherman had failed even to identify, much less summon to the stand, an independent witness who could have corroborated Michael’s alibi that night. A grand jury transcript that was available to Sherman before trial and should have been reviewed by him as a matter of course showed that Michael’s aunt, Georgeann Skakel Dowdle, had testified that she had been present with her “beau” when the carload of kids from the Skakel house came to her home to watch Monty Python the night of the murder.

The investigator for Michael’s present lawyers had little trouble identifying the beau as psychologist Dennis Ossorio, now 72 and retired. He told the court that he had lived in the Greenwich area during the trial and would have been available to testify. He now testified at the hearing, as he almost certainly would have at the trial, that he had a gone into the TV room while his girlfriend was putting her daughter to bed and clearly remembered Michael being among the boys who were there.

“To the best of my recollection we watched most of the show,” Ossorio said.

“Did the Greenwich police ever interview you?” Michael’s present lawyer, Santos, asked.

“No,” Ossorio said.

“Were you contacted by [Sherman]?” Santos asked.

“No,” Ossorio said.

In his written ruling, Judge Bishop was not swayed by Sherman’s testimony at the hearing that his client had never mentioned Ossorio being at the house that night. Bishop noted, “Had Attorney Sherman read and considered Dowdle’s grand jury testimony, which was made available to him before the trial, he would have learned of the presence of an unrelated person in the Terrien household. And, had Attorney Sherman made reasonable inquiry, he would have discovered Ossorio and gleaned that Ossorio was prepared to testify that the petitioner was present at the Terrien home during the evening in question. He would have learned, as well, that Ossorio was a disinterested and credible witness.”

Bishop was equally disapproving of Sherman’s failure to locate and present three former Elan residents who could have impeached Coleman’s testimony, noting that another court had ruled they did not constitute new evidence for the very reason that a diligent attorney could have found and presented them. Bishop further noted that, in testimony submitted as part of that earlier appeal for a new trial, an Elan alumna named James Simpson had described being in a room with Michael Coleman at the time of the supposed confession.

“Simpson stated that suddenly, Coleman exclaimed that the petitioner [Michael Skakel] ‘just admitted that he killed this girl,’” Judge Bishop wrote. “Simpson stated that he turned to the petitioner and asked him if he had just made such an admission to which the petitioner responded ‘No.’ Simpson then confronted Coleman by asking him how he could say that the petitioner had just confessed to murder when the petitioner denied saying any such thing and Coleman replied that when he asked the petitioner if he had killed the girl, the petitioner didn’t reply and that he had a shit-eating grin.’

“Simpson stated that Coleman said that it was the petitioner’s reaction to the question, and that he didn’t deny it. Simpson explained that it had become evident upon his questioning of the petitioner that he had made no such admission. Simpson stated, as well, that he never heard such an admission at any other time; nor did he ever hear the petitioner claim that he'd get away with murder because he was a Kennedy.”

The judge went on, “In sum, Simpson not only denied hearing the petitioner make an admission or brag that he would get away with murder because he was a Kennedy, but his recitation of the incident directly contradicts Coleman’s testimony.”

The judge added, “Simpson also opined, based on his observations of Coleman at Elan, that Coleman was envious of the petitioner. Simpson stated that Coleman had told him that the petitioner was a Kennedy and that he didn’t have to work for anything.”

The judge continued, “He believed that Coleman did not like the petitioner. Furthermore, on the basis of his observations of the relationship between Coleman and the petitioner, Simpson stated that he did not believe that the petitioner would ever confide in Coleman. Finally, Simpson stated that, to his knowledge, the petitioner was never accorded any special privileges at Elan; in fact, it was his view that the petitioner was harshly treated there.”

Judge Bishop found Sherman equally negligent in failing to rebut the prosecution’s claim that the Skakel family had stashed Michael in Elan to keep him away from the police. Bishop quoted the prosecutor saying during the closing, “One thing that I submit helps tie all this together, particularly on the subject of Elan, and really see the truth, is the defendant’s very presence at that place.”

The prosecutor had reminded the jury of all the pressure on Michael to explain why he had killed his neighbor. The prosecutor had then asked aloud how Elan had found out about the murder in the first place.

“The answer, the only one that makes sense, lies in why the defendant was there in the first place, lies in why his family felt a need to put him in that awful place,” the prosecutor had said. “Why? Because that’s what they decided that they had to do with the killer living under their roof.”

Judge Bishop now wrote that a definitive refutation of this contention was contained in documents that the prosecution and Sherman possessed.

“The Greenwich police file indicates subsequent direct contacts between Elan and the Greenwich police,” Judge Bishop wrote, noting that the contacts began shortly after Michael was sent there and included conversations between investigators and the facility’s staff.

Judge Bishop went on to say, “Attorney Sherman should have known that the Greenwich police had been made well aware of the circumstances of the petitioner’s admission to Elan and he should have offered evidence in response to the state’s false claim in this regard.”

But along with his failure to corroborate the alibi, Sherman’s biggest error in the judge’s view seemed to be not presenting Tommy Skakel as an alternative suspect.

“Given the evidence of T. Skakel’s culpability available to Attorney Sherman before trial, there was no reasonable basis for his failure to shine the light of culpability on T. Skakel,” the judge wrote.

Judge Bishop dismissed Sherman’s assertion during the trial that Littleton had been a stronger alternative suspect. Bishop allowed that the court was required “to accord considerable deference to strategic choices made by trial counsel,” but further noted that “the law does not command ignorance to substantial evidence that choices made by counsel were unreasonable.”