William Blake, the eighteenth century poet, illustrator, engraver and mystic, worked from home but lived in his imagination. It was the place, he insisted, where “the eternal and the real meet.” Besieged for much of his life by visions of imaginary visitors such as the archangel Gabriel and Michelangelo, Blake’s imagination was the watering hole from which all his creative needs quenched their thirst.

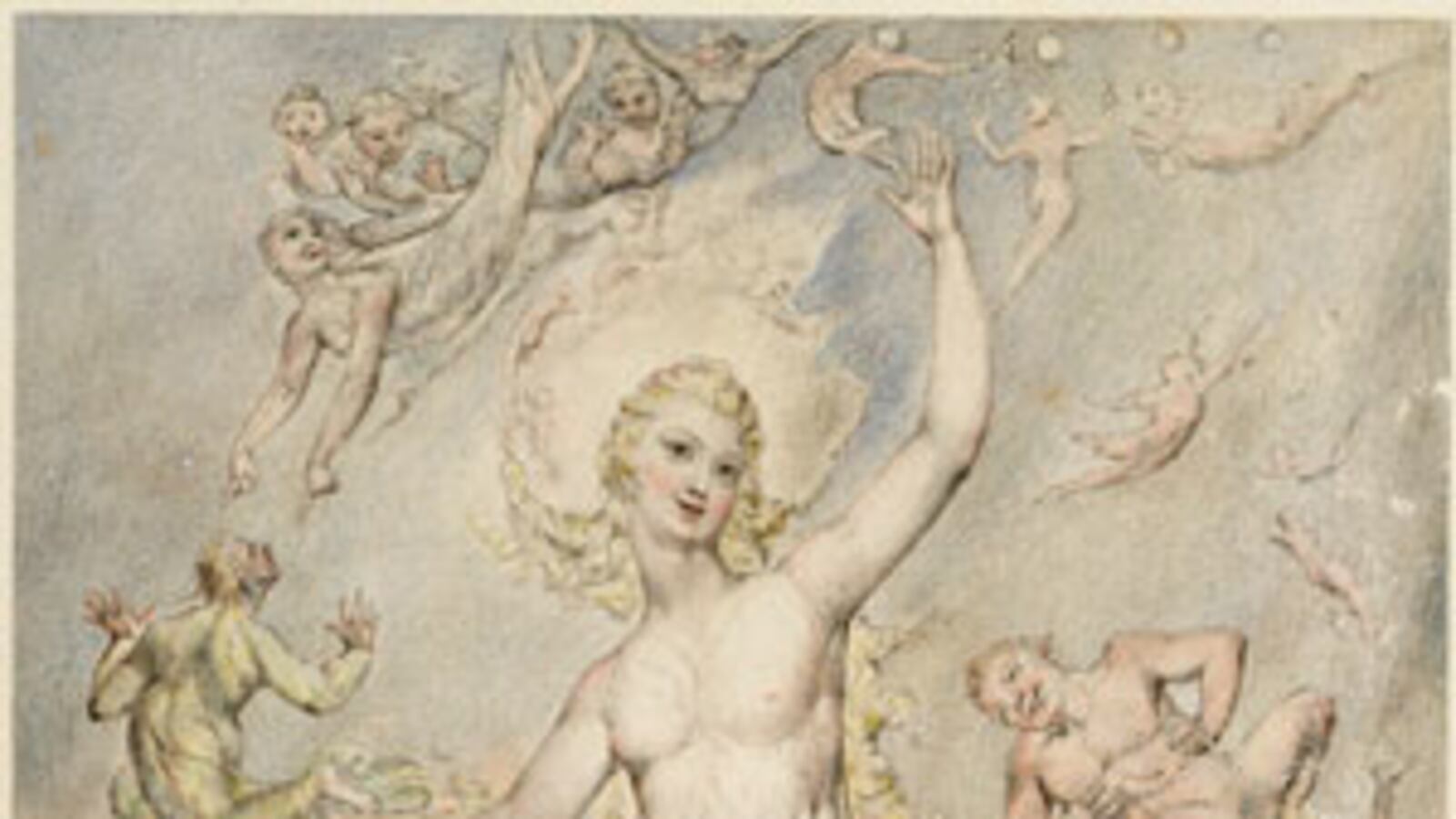

The Morgan Library and Museum’s fall exhibition, William Blake: A New Heaven Is Begun, on view through January 3, 2010, is a comprehensive and varied retrospective of the fruits of Blake’s imagination. The show includes over 100 examples of Blake’s poems, engravings, watercolors, and illuminated books and is culled entirely from the Morgan’s private collection.

Click Image Below to View Our Gallery

Including two original copies of his most famous poem, The Tyger, one with color added by hand and one without, and one of the sixteen original copies of the celebrated illuminated book of poems, Songs of Innocence, the collection is regarded as one of the country’s finest. Begun by Pierpont Morgan in 1899 and continued by longtime museum director Charles Ryskamp, the inspired collection maps a deft chronology of Blake’s life and work.

Despite being known posthumously for his poetry and illustrations, during his lifetime Blake was primarily known as an engraver, the art form being the only one that earned him his meager living. He was known by most as Mr. Blake The Engraver, though by others as the crazy guy with visions.

Blake’s skill as an engraver is often over-looked as art-lovers tend to focus on the mystical and fantastical nature of his illuminated poems. However, the poet faithfully defended his livelihood, insisting that engraving was a true art. He famously said, “Painting is drawing on canvas and engraving is drawing on copper and nothing else.” He employed a number of techniques and steps in his engraving process ranging from relief etching to white-line engraving, monotype printing and hand finishing with pen and watercolor.

• Art Beast: The Best of Art, Photography, and DesignHis craftsmanship and skill with engraving are particularly interesting when viewed in contrast to the seemingly impulsive and mystical nature of his illustrations and writing. His art can often seem divinely inspired, the inspiration apparent in an instant demanding to be chronicled with immediacy before disappearing. But engraving is a painstaking and laborious art that requires patience, precision and lack of whim. At 46, Blake wrote, “I curse and bless Engraving alternately because it takes so much time and is so untractable, tho capable of such beauty and perfection.” But that tedium and intractability is hidden in the weed-like growth of poetry and illustrations that take center stage on the page.

Whether intentional or not, the show is curated in a similar spirit; a seeming dense forest of engraved plates, watercolored illustrations and illuminated poems, the one room exhibition is subtly but unmistakably aligned. Beckoning the innocent viewer to follow a path around the room, the exhibit is discreetly oriented thematically with a different theme or period addressed on each wall.

The exhibit begins with an audio station boasting Jeremy Irons’ reading of The Tyger. The British actor’s unmistakable voice lends itself well to the dark lilts of the poem, though I found it difficult to separate the actor’s faceless voice from his portrayal of Humbert Humbert and that, well, distracted me from the Bengali feline being described so majestically.

The southern wall of the gallery is dedicated to friends and followers, who referred to themselves as “ancients” in reference to Blake’s frequent allusions to earlier artists such as Milton and Michelangelo as Ancients. Emerging artists such as John Linnell, Henry Fuseli and John Flaxman were just a few of those who considered themselves Blake’s followers, or ancients.

Generally considered to be a total wack job by his contemporaries, Blake owes the perpetuation of his work to this group of admirers, who were responsible for Blake’s continuing influence on future generations. The kooky poet was rarely taken seriously except by this group of followers and his believing wife, Catherine Boucher. A highlight of this wall is Samuel Palmer’s “Pear Tree in a Walled Garden.” An 1831 print with a mountainous backdrop that eerily pre-dates Cezanne’s revolutionary geometric planes.

The west wall displays Blake’s breathtaking illustrations for The Book of Job, commissioned by his most important patron, Thomas Butts.

In Blake’s version Job’s major flaw is attending to the letter, rather than the spirit of God’s law. And indeed, Blake held this common error in contempt in all walks of life, religious, political, social.

These illustrations were executed in the style recognized as more typically Blake-ian than the Watteau-inspired prints he began his career, and the exhibit, with. But his inspirations are clearly present, it is easy to see his love of Michelangelo in the anatomically defined gluteus maximus of Satan before the Throne of Man. Satan looks more like an Equinox advertisement than the horned hell raiser we are accustomed to.

Blake revered the Renaissance master and famously claimed that his birth marked the beginning of a “new heaven” where, explains the curator’s introduction to the exhibit, “his art would exemplify the creativity prefigured by Milton and Michelangelo.”

Blake’s trilogy of illuminated books produced in 1783, called “The Continental Prophecy,” monopolizes the north end of the room.

The books weave an anti-monarchist and revolution-spirited narrative driven by the mythological hero and anti-hero, Orc and Urizen, respectively. Despite sounding like characters in a new Peter Jackson trilogy, the mythological figures form a brilliant symbiosis of mythos and political commentary. Legalistic and despotic Urizen was Blake’s inspired vehicle for expressing contempt for the current political regimes.

His predilection towards creating and re-interpreting stories that challenge moral, religious and political conventions is redolent in both his original texts and his choice of texts to illustrate, such as Milton and the Bible.

Blake’s illustrated books and poems proved, in many ways, a radical bridge of mediums, boldly secularizing the illuminated manuscript while presciently laying the groundwork for the graphic novel.

The cover plate for the eighteen-page poem, “America A Prophecy” is spartan in illustration making the text the central focus, a sort of Romantic’ Ed Ruscha.

On the last plate of “Europe A Prophecy,” the word finis is delicately etched in curling script intertwined amongst a den of brambles.

An original copy of Songs of Innocence, one of only sixteen, is saved climatically for last. The book is opened to the cover page and is shielded in a glass display box. The detail and majesty of the illustrations are impossible to appreciate in the reprinted book editions, though beautiful, the topography of the work is absent and therefore lost to the reader. Up close the color, added by hand after printing, is soft and dappled, and the paper is slightly raised like a new mosquito bite.

To create these ornate illuminated manuscripts, Blake delved deep into the darkest corners of his imagination. In Poems for the Millennium he tried to explain the mystery of it all, “What is now proved," he wrote, "was once imagined.” Apparently William Blake had a lot to prove.

Plus: Check out Art Beast for galleries, interviews with artists, and photos from the hottest parties.

Chloe Malle writes for The New York Observer, The Huffington Post, WoWoWoW and Tadias Magazine. She lives in New York City.