“Hey, Golub, you’re going to get a call from Sandra Jennings, the ballerina,” Paulie Herman said over the phone in 1989.

Herman is an actor frequently seen in Robert DeNiro films, recently cast as Whispers DiTullio in The Irishman. At the time of the call, he was the manager of celebrity hangout Cafe Central on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, warning me over the phone.

“She says she was married to William Hurt, I know she lived with him.”

That got me hooked. I loved Body Heat, but not as much as suing celebrities back then.

The next thing I knew on a hot May day there was sweet, plain Jane, Sandra Jennings in my office telling me about her relationship with Hurt.

The case excited me and back then it didn’t take much. I furiously took notes on their time together in Beaufort, South Carolina, back in 1982-1983 when Hurt was acting in The Big Chill. She wanted half of the money he had earned while they were together.

New York had abolished common-law marriage in 1933, but South Carolina still recognized it. I made up my mind that I could win this one if I could get a New York court to apply South Carolina law. After all, during an argument, the recently divorced Hurt, who had studied theology at Tufts and was religious, had shouted at Jennings, “We are married, married in the eyes of God.”

Although the case was about establishing that Hurt and Jennings were married, equally compelling was that the facts were riddled with his cruel and abusive behavior toward Jennings and their son, Alex, and—as everyone now knows—other women. You could say I got personally involved, and how could I not? Seven-year-old Alex was at my office every day for months and so was Jennings. It was impossible not to sympathize with a boy who had been ignored by his father and a woman who had been mistreated by the father of her child.

In her lawsuit, Jennings said Hurt had smashed her in the face while she held newborn Alex. She said she left him because of his “constant abuse, drunkenness, violence, and total dishonesty.”

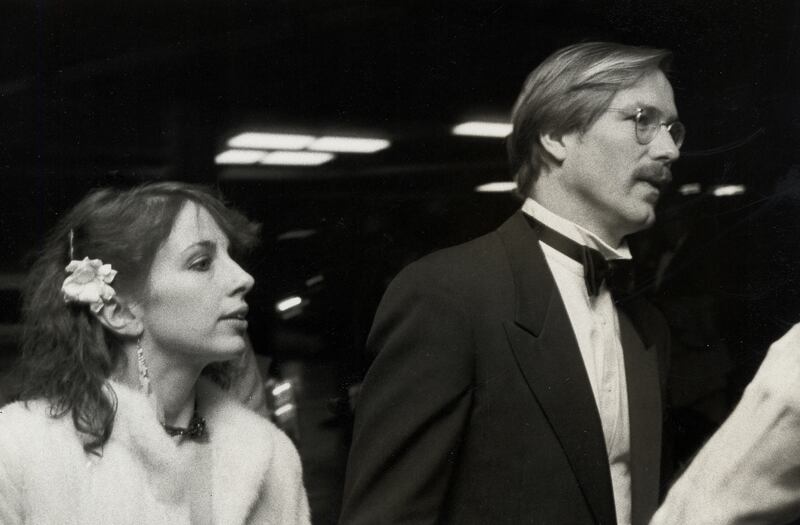

Sandra Jennings and William Hurt at the 54th Annual Academy Awards.

Ron Galella/Ron Galella Collection via Getty ImagesI got to see his blistering anger first-hand. Before the trial started, there were conferences with the judge in chambers. At the first one, Hurt and the sparrow-like Martin Shelton, his lawyer from Shea & Gould (now defunct and, in my opinion, one of the most corrupt law firms that ever existed in New York), were present along Sandra and myself.

Before it even got underway, I warned Hurt to stop firing his carpenter’s staple gun around his young son, who had complained to Sandra that he was afraid of his father for more than one reason. Without hesitation, Hurt jumped out of his chair and lunged at me from the other side of the conference table. Then Shelton took a swing at me. I ducked out of Hurt’s way, bobbed to the side of Shelton and said, “Marty, if I hit you, I’ll kill you.” The court officer restrained Hurt, whose face was cherry red. That was a sample of what Hurt was capable of, and he should have been locked up on the spot.

At the trial, Jennings’ testimony wasn’t exactly consistent with her preparation but was sufficient, in my opinion, to prove that she and Hurt had the legal makings of a marriage pursuant to South Carolina law. Sandra equivocated on some issues—more a result of her artistic temperament, not because she was not telling the truth.

Following her testimony, Hurt took the stand and rebutted her testimony that he’d ever told Sandra that they were married in Beaufort, South Carolina. My cross-examination initially went like this:

“Did you discuss your philosophy toward marriage?”

“I made my position very clear to her,” Hurt replied.

“What was your position?”

“My failure at marriage and my family’s failure at marriage. I had gotten burned,” Hurt answered.

“What do you mean burned?”

“Scorched.” Hurt replied. He smiled broadly at the full courtroom and drew lots of laughter.

“Scorched?” I asked

“Wounded,” Hurt said quietly.

“Body Heat,” was my retort.

“Get off it,” Hurt replied, his anger escalating.

That’s when the fireworks started. Right then Shelton started making a throaty, frog-like noise, causing me to turn to him:

“Marty, can you cut that out, you’re screwing up my rhythm.”

I turned to the judge, “He’s interrupting my rhythm and rhythm is everything.”

It was then Hurt said to me, “You’re amazing, putting on a show. Get your rhythm right.”

“You had yours right, pal when you had your son Alex,” I shot back.

Hurt turned to the judge and started to get out of the witness chair in his pin-striped suit, clearly coming for me.

“You can permit that?” he said. “What you just said is an insult to me, you understand? He’s mucking around with the conception of my son, making a perverse, insulting little joke about it. Right now I’m very angry. I’m blocked. I can’t hear anything else.”

Hurt and I were right in each other’s faces when the judge ordered me, “Richard, get back.” She then called a recess.

I complied and there was Hurt’s uncontrollable temper, witnessed in public first hand.

At the end of the testimony, the judge decided there was no common-law marriage because Hurt and Jennings never met the legal standard of “holding themselves out” as man and wife in South Carolina.

During the trial, one of the stories that circulated was that when Hurt was living with Marlee Matlin in Sneden’s Landing, New York, a celebrity lair, he bloodied her one Sunday morning, leaving her on the floor of the living room. He then took a shower, dressed in white suit and went off to church.

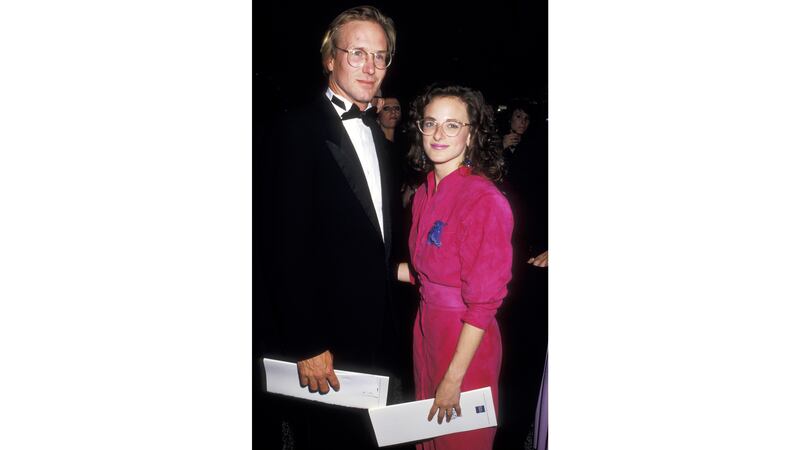

William Hurt and Marlee Matlin at the 41st Annual Tony Awards.

Ron Galella/GettySandra repeated that story in public and when I ran into Matlin years later, I asked her about the incident. She refused to answer me. She didn’t deny it and in her 2009 autobiography, I’ll Scream Later, she accused Hurt of physical violence and rape. Hurt later said in a statement: “I did and do apologize for any pain I caused.” Author Donna Kaz also accused Hurt of domestic violence, though he did not respond.

Hurt is dead and isn’t able to refute any of the nasty things said about him by women who have come forward over the years, whose stories were given a second life by his passing. His death has allowed his full character to be exposed, not just the one that he crafted for the public. He was, after all, a master of delivering lines. I recall that during his deposition, after I asked him about the alleged marriage in South Carolina, Hurt had this response:

“I don’t know, give me the script and I’ll give you the answer.”