Mulholland? Sure, you say. I know that name. Isn’t it a twisty street somewhere in Los Angeles, and wasn’t Mulholland Drive the title of an eerie film by David Lynch? And didn’t Roman Polanski and Robert Towne’s movie Chinatown have a character with the sound-alike name of Hollis Mulwray, the L.A. city water engineer who is murdered for refusing to forget the mysterious collapse of something called the Vanderlip Dam and threatening to expose John Huston’s sinister water grab?

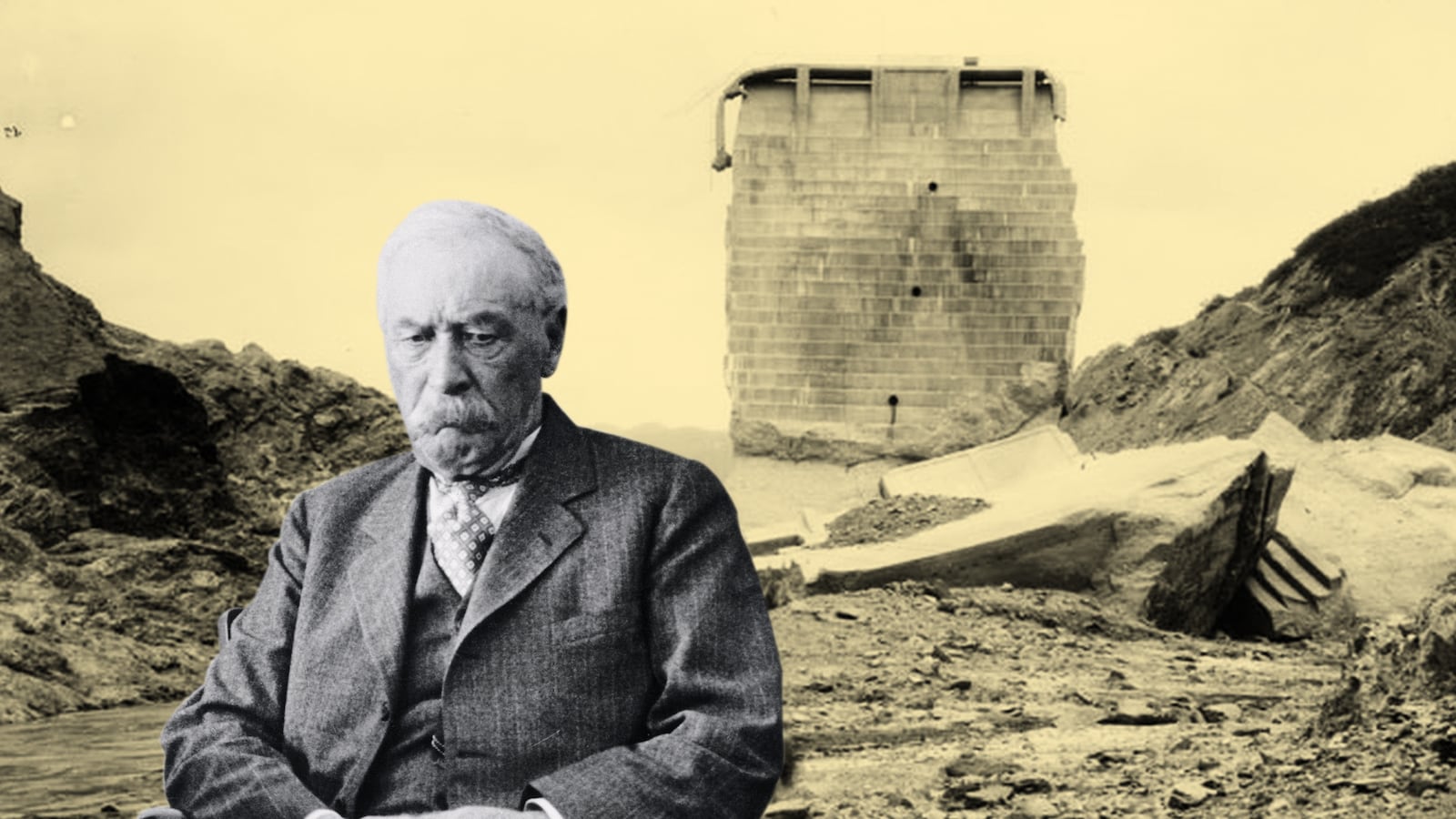

In fact, there was a real William Mulholland and his life was the kind Americans admire and mythologize, including humble beginnings, hard work, and mostly self-taught expertise, leading to an unprecedented engineering achievement that launched and sustained the rise of America’s second-largest city, and ending with a fatal disaster considered the worst in 20th-century U.S. history. (When I wrote my new book, Floodpath: The Deadliest Man-Made Disaster of 20th Century America and the Making of Los Angeles, there was no question but that Mulholland would be the narrative’s driving force.)

Born in Ireland in 1855, young Willie Mulholland ran away to sea when he was 15, and in 1877 followed his sense of adventure to Los Angeles, a frontier town with a welcoming climate and a population of a little more than 11,000. The year before, the once isolated Mexican pueblo gained easier access to the rest of the United States with the arrival of the transcontinental railway.

In 1878, at age 22, Mulholland started his life’s work as a ditch digger for the city’s privately managed water distribution system, which was linked to the shallow Los Angeles River. In the years that followed, the Irish immigrant’s no-nonsense attitude and management skills led him to the leadership of a new city-owned water department in 1902. By then, the population of the sunny City of the Angels had boomed to more than 102,000, nearly 10 times what it was when Mulholland rode into town. If the trend continued, it was clear L.A.’s thirst would overwhelm the undependable Los Angeles River. In 1904, anticipating this dire forecast, former mayor Fred Eaton came up with an audacious scheme to import water from the Owens Valley, located more than 200 miles away beneath the snow-covered Eastern Sierra.

Enlisting the secret support of local political and business leaders, without letting Owens Valley farmers and ranchers, or even Angelenos, know what he was up to, Eaton bought the land and water rights needed for an unprecedented 233-mile-long aqueduct, which could use gravity alone to carry a man-made river south. Before plans were public, anticipating a real estate bonanza, insider businessmen led by Harrison Gray Otis, owner of the Los Angeles Times, quietly bought property options in the San Fernando Valley, where the aqueduct was expected to end. Funding for the project came from East Coast investors, and William Mulholland enthusiastically accepted the challenges of design, construction and getting the job done—on time and on or under budget. It would be the longest liquid pipeline in the world—at the time a job compared to the building of the Panama Canal.

When L.A.’s secret was revealed, Owens Valley residents were furious to learn they’d been hornswoggled. They were even angrier when Teddy Roosevelt’s Progressive federal government sided with Los Angeles, considering the issue a case of allocating natural resources to provide “the greatest good for the greatest number.” When the water arrived on Nov. 5, 1913, improbable Los Angeles was poised to become an important American city.

To 20th century Progressives, William Mulholland, nicknamed “the Chief,” was a dream come true—a model public servant and get-it-done engineer, selflessly dedicated to defending and expanding the future of the city of Los Angeles, and apparently above politics. Once, when the Chief was asked to run for mayor, his demurral was characteristic: “I’d rather give birth to a porcupine backward.”

Angelenos may have been charmed, but Owens Valley activists saw Mulholland as a threat to their survival. The result was a rural vs. urban conflict known as “California’s Little Civil War.” When lawsuits proved too slow, valley activists turned to direct action—repeatedly blasting Mulholland’s aqueduct with dynamite.

Although more determined than ever, the Chief was caught in a three-way crossfire. Angry Owens Valley residents charged that big city L.A. and the federal government had colluded to invade their private property and “steal” their water. In Los Angeles he was confronted by the city’s small socialist-leaning political left, suspicious of aqueduct-related real estate profiteering by L.A.’s business oligarchy. At the same time, from the right, Mulholland was targeted by free-enterprise capitalists staunchly opposed to publically owned utility systems like L.A.’s municipal Department of Water and Power, soon to be the largest in the United States.

These clashes came to a head during the ’20s, another period of unprecedented growth for Los Angeles. Fixated on tomorrow, Mulholland eyed the resources of the Colorado River as he launched an ambitious program to build new dams and reservoirs to store Owens Valley water closer to Los Angeles. Completed in 1926, the largest, the 208-foot-tall arched concrete St. Francis Dam, located in isolated San Francisquito Canyon 50 miles north of Los Angeles, impounded 12.4 billion gallons. City-owned power generating plants above and below the reservoir, driven by falling aqueduct water, supplied 90 percent of L.A.’s electricity.

On the morning of March 12, 1928, Mulholland and his assistant, Harvey Van Norman, were called to examine a leak in the St. Francis Dam. Leaks were not uncommon, but watchman Tony Harnischfeger thought the escaping water looked muddy, an alarming sign that the dam’s foundation could be failing. When Mulholland took a close look, with nearly 50 years of experience, the water appeared clear. Van Norman agreed. They concluded the leak became muddy when it mixed with construction debris. Shortly after noon, the water department bosses returned to Los Angeles. Less than 12 hours later, shortly before midnight, the St. Francis Dam suddenly shuddered, heaved, and cracked apart, releasing a flood that surged west through small agricultural towns and farmland, destroying nearly 500 lives before reaching the Pacific Ocean 54 miles away.

The failure of the St. Francis Dam is the second-greatest disaster in California history, after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, and a 20th century counterpart to the 1889 Johnstown Flood. But unlike these far better known catastrophes, the tragedy wasn’t caused by an “act of god” earthquake or torrential rainstorm. In the aftermath, California’s Little Civil War was transformed by harrowing life-and-death struggles to survive, urgent investigations, a technological detective story, and an intense courtroom drama that changed the course of dam building in California, America, and even around the world.

Although William Mulholland never publically accepted official explanations of the collapse based on a faulty foundation, and possibly suspected a dynamite attack, he took full blame. “The only ones I envy about this thing are those who are dead,” he said. By the time the Chief died in 1935, his reputation was overshadowed by disgrace. The American West wasn’t wild anymore, and in Mulholland’s lifelong race against the future, he’d been outrun by social, political, economic, and engineering changes he was unprepared or unwilling to acknowledge.

It wasn’t long before the St. Francis Dam disaster was mostly forgotten, buried by L.A.’s prompt restitution and eagerness to ignore loose ends, along with a national enthusiasm for a new era of transformative hydroelectric projects, including Hoover Dam.

Despite 88 years of obscurity, far from outdated news, the lessons of William Mulholland’s successes and the failure of the St. Francis Dam are more relevant than ever in a 21st century era of climate change, international challenges to water resources, and an ignored and failing American infrastructure. Even in today’s age of computer assisted design, dams can fail and people die, not only from faulty design, but as a result of ignored or postponed maintenance after decades of holding back tons of water. A 2013 American Society of Civil Engineers “Report Card” for America’s infrastructure gave dams a grade of D+ and more than 4,400 were judged susceptible to failure. So far no one seems interested in responding to this ticking time bomb.

In Robert Towne’s Chinatown screenplay, when private eye Jake Gittes’s investigation hits a dead end, he’s warned he’ll never understand. “Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.” Too often, the history of Los Angeles, reduced to Tinsel Town and surfboard stereotypes, gets the same dismissive treatment, but the life of William Mulholland and the tragedy of the St. Francis Dam are reminders that overlooked lessons from L.A.’s past deserve exploration informed by facts, not film noir fictions. As unprepared Angelenos or visitors often discover, the curves of Mulholland Drive can be treacherous.

Jon Wilkman is an award-winning documentary filmmaker. His television series Moguls and Movie Stars: A History of Hollywood was named one of the year’s top ten programs by the New York Daily News and the Wall Street Journal, and nominated for three Emmy Awards, including writing. Wilkman also is the author, with his late wife, Nancy, of two books about Los Angeles. He is now at work on a documentary on the St. Francis Dam disaster. Please visit his website wilkman.com.