For the last four days, the World Science Festival—an eclectic and lustrous gathering of scientists, writers, artists, and celebrities—has descended on Manhattan, attracting thousands of participants to forums on science's newest, hottest findings.

Thursday night, four researchers gathered to debate questions of longevity, including: To what extent might it be possible to extend the human life span? How long is desirable? What is available now to slow down the aging process, and what are the most promising methods under development?

Judith Campisi, who studies aging at the Buck Institute, spoke in vivid and succinct language about her lab's current focus. Two things become more likely with age, she said: degeneration and cancer. Yet in many ways, she continued, these two processes are opposite to one another, the former based on a slowing down, a loss of function, the latter, a speeding up of cell division. Yet both are more likely to occur the older we become. The question for Campisi now: What is the common mechanism underlying both? What is it about getting older that should make both things more likely? And can this common mechanism give us insight into the question of how we might go about living longer, healthier lives?

The three other scientists on stage included the controversial—many would say disreputable—Aubrey de Grey, a British gerontologist with a foot-long beard who claims that the first human who will live to turn 1,000 has already been born. In a monotone further muffled by his beard, de Grey described his belief that aging as we know it is not an inevitability and that, just as a car can be refurbished and refreshed, so too can the human body, which is, he believes, just a machine, "a really complicated machine."

Michael Rose, an evolutionary biologist and one of the field's luminaries for his work manipulating the life span of fruit flies, discussed his belief in "the cessation of aging"; which is to say that once humans hit a certain age, aging stops. So now, says Rose, the challenge is to move up the point at which we cease to age.

Finally, Leonard Guarante, from MIT, discussed relatively familiar methods that have empirical support for their longevity-boosting effect: one, Resveratrol, the much-touted antioxidant in red wine, and two, a calorie-restricted diet. But the latter is no mere skipping of dessert— "calorie restriction" refers to intermittent fasting—dropping down to 50 percent or less of what a human typically consumes. The people who manage this, said Guarante, do look younger as they get older. The downside? "They're miserable all the time," he says. Coming down the pipeline, he said, are drugs that could achieve the cell-renewing effects of calorie restriction, without the negative affect that the diet has on quality of life.

The consensus? Longevity researchers may not agree on the means, but many believe that human life span and quality of life are both candidates for radical improvement, if not full-out reinvention.

The festival, only in its fourth year, is an energetic event and puts on full display the personalities of many of science's most notable members. One of the most interesting discussions of the week featured a group of famous scientists who also are famous for the books they've written.

James Watson, of the Nobel Prize-winning team that discovered the structure of DNA, played up his curmudgeonly persona to the max. About Sarah Palin, he remarked: "She doesn't know anything." On the choice of Jeff Goldblum to play him in the movie of his life: "At least it wasn't Richard Dreyfuss."

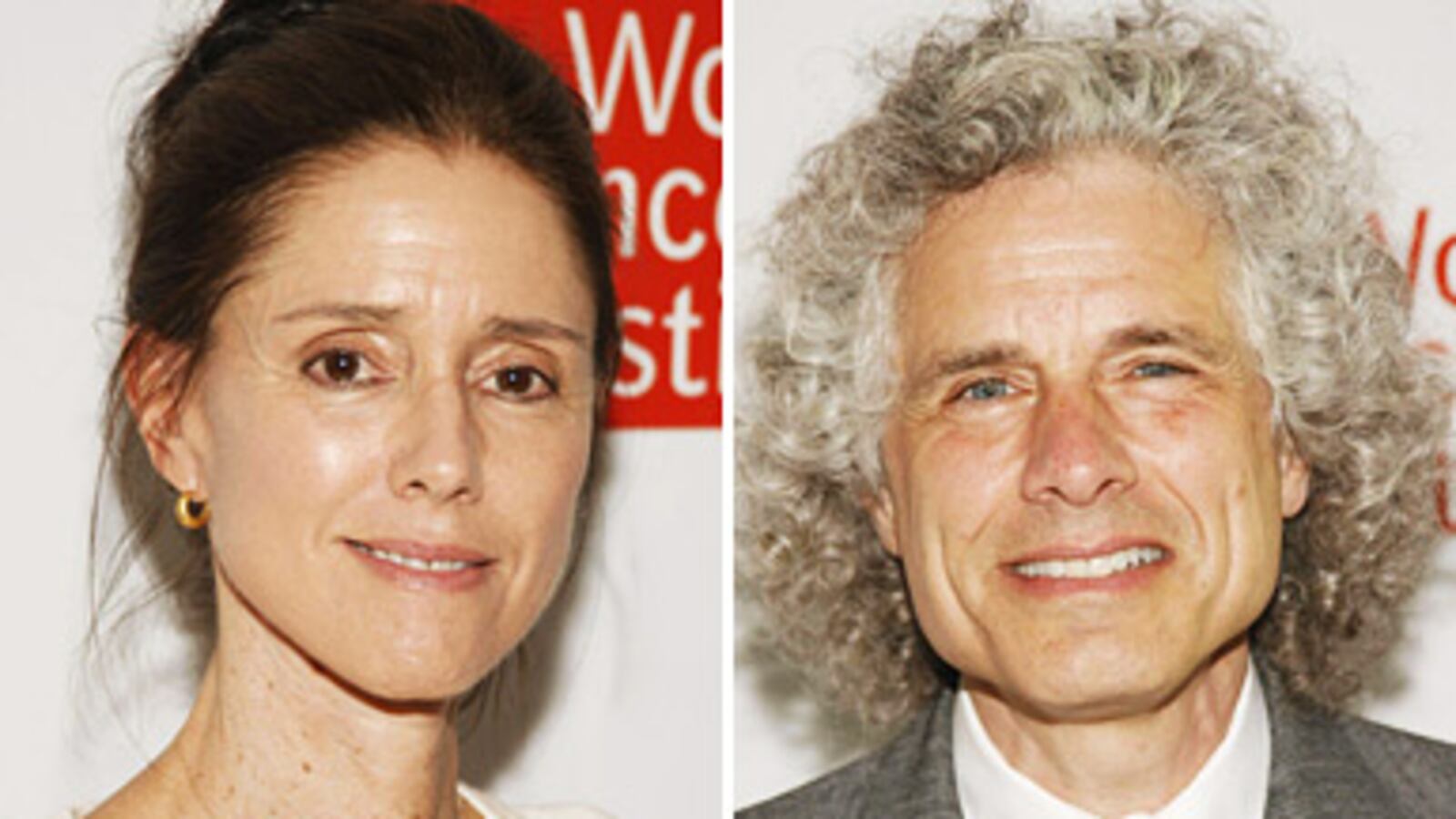

But still, Steven Pinker, the Harvard psychologist and author of How the Mind Works, managed to slip in an excellent piece of advice: Scientists who write should never make the mistake of talking down to their readers, or imagining their readers as being less intelligent. Instead, they should think of their readers as "their college roommates" who wound up in fields other than science.

Also on stage was the elegant Siddhartha Mukherjee, a cancer doctor and author of the bestselling The Emperor of All Maladies. Mukherjee remarked that good writers and good scientists, by definition, share a deep uncertainty about their own way forward. It is this sense of anxiety, this not knowing, he said, that keeps their work interesting and vital.

Memory is an extremely hot topic in the neurosciences, and was featured in two different forums during the festival, in discussions that explored how memories are stored in the brain and to what extent they change over time.

On Saturday, a panel of several prestigious memory researchers, including Todd Sacktor, Joe LeDoux, and Elizabeth Phelps, talked about the groundbreaking discovery that even those old, familiar recollections, well ensconced in long-term memory, are subject to revision every time they're recalled. This discovery, made only a decade ago, has ushered in a wave of inquiry into what is known as "memory reconsolidation"—going beyond the question of how the brain encodes experiences into memory to explore how the brain rewrites old, existing memories.

From this research come myriad applications, currently under investigation. For instance, people who have post-traumatic stress disorder suffer from excessively vivid and recurrent traumatic memories. Neuroscientists working on the cellular levels of memory posit that it might soon be possible for these traumatic memories to be interrupted, altered, or even erased.

It sounds like the stuff of science fiction, but over the last five years, selective tinkering with human memory has become an increasingly realistic possibility; Saturday's panel on "manipulating memory" made clear just how far the study of memory has come.

The big marquee event of the festival was Saturday night's discussion on "the enigma of genius." What is genius? Who decides? What can be understood about genius from the point of view of the brain? Is genius born or made?

On stage, a motley group assembled to dig into these questions, including Julie Taymor, the accomplished film and stage director, who's been in the news this year because of the disastrous events associated with her efforts to bring Spider-Man to Broadway; the storied composer Philip Glass; Marcus du Sautoy, an Oxford mathematician, and three scientists who study human intelligence.

One of them, Dean Keith Simonton, discussed the changing definitions of genius through time. According to Immanuel Kant, a genius could be understood as someone whose work was both "original and exemplary."

But the people on stage had other attributes they considered indispensable: a complete independence of mind, said Glass, as well as stamina, endless stamina.

Taymor observed that genius was not just a matter of originality, but rather, of the personal imprint an artist, scientist, or thinker puts on his or her material. After all, she observed, as with so many geniuses in history, Shakespeare's work is replete with ideas not his own, but they emerge anew within his particular, incomparable renderings.

R. Douglas Fields, a neuroscientist at the National Institutes of Health, had much to say about what characterizes the brain of geniuses.

According to Fields, the real difference between the brains of geniuses and non-geniuses appears to revolve around brain cells known as "glia," which for years were thought to be the mere "glue" of the brain, "support cells," second-class citizens compared to neurons.

This notion began to shift in the late 1980s, when Einstein's brain was dissected, in an effort to see if there was anything unusual about its anatomy. What researchers discovered was that Einstein's brain was no different from the average human brain except that, in several regions, Einstein had significantly more glial cells. That, said Fields, "was a moment that focused our attention on glia."

On the question of early experience, Fields made a somewhat startling assertion. "All these great creative people started young," he said. "The brain that you have for the rest of your life is determined by what you do with it up until the age of 20."

Rex Jung, a neuroscientist who studies creativity, remarked that intelligence and creativity are not synonymous, and that the differences between them are even reflected in brain structure. As far as intelligence is concerned, the rule for brain structure is that "more is better," Jung said. "More gray tissue, greater white-matter integrity, thicker wires, more myelination."

But, he said, in terms of creativity and its relationship to the structure of the brain, "the story appears to be that less is better. Less white-matter integrity, lower gray-matter tissue, particularly in the frontal lobes."

This is likely because truly creative thinking requires a freeing-up of the thought process, a kind of "disinhibition" that allows associations to be made between previously unrelated ideas.

Jung remarked that flashes of creative thought often come in moments of "hypo-frontality," which is to say, a state of deep relaxation in which the frontal lobes, the great executives of the brain, are dozing. Beethoven took long walks, Jung said, and Archimedes, hot baths.

The importance of "hypo-frontality" in arriving at novel solutions was true for Julie Taymor, who reported that some of her greatest breakthroughs come from "early morning sleep." "I get up," she says, "and the thing has become clear very fast."

Taymor, who hasn't had the easiest year, spoke of her own creative process with an alluring intensity that brought alive the more scientific aspects of the presentation.

It was an interesting conversation and a fitting end to three days of heady and unusual ideas.